Glasswing Butterflies Want To Make Something Perfectly Clear

Bay Area biologists are studying a beautiful and exotic butterfly with the hope that their findings may one day improve technologies from eyeglasses to solar panels.

Named for their transparent wings, glasswing butterflies have evolved a clever disappearing act to avoid their many predators in the rainforests of South and Central America.

“Most things in the rainforest are either bright and flashy or they’re trying their best to hide,” said Aaron Pomerantz, a doctoral candidate in the Nipam Patel Lab at UC Berkeley and the Marine Biological Laboratory. “There aren’t a lot of things that are just trying to be invisible like the glasswings.”

Many butterflies hide by blending in with their surroundings. This strategy can be effective, but only when the butterfly stays on a matching background.

Others try to stand out by using bright colors and clashing patterns that serve as a warning to predators. They typically eat plants rich in chemicals that make them poisonous or distasteful.

Glasswings are different. Their transparent wings allow them to hide against any background — even while flying.

So how do they do it?

Most butterflies are covered with row after row of tiny colorful scales, each about the size of a grain of salt. The flat scales protect the butterfly — similar to the scales on a fish or the shingles on a roof. The butterfly’s scales also keep rain from sticking to its wings, weighing it down.

Glasswing butterflies do have scales on their bodies and on the edges of their wings. But scales on the transparent sections of their wings look completely different — more like tiny hairs barely visible to the eye.

The hairs help protect the surface of the wing and repel water, but they are thin and spaced apart from each other, so they don’t block light from hitting the surface of the wing.

A butterfly’s wings, like the rest of its exoskeleton, is made out of a tough material called chitin. Pure chitin is actually clear, but in most insects the chitin also contains pigments that absorb light and make the chitin opaque.

“What the pigments don’t absorb, they reflect back,” Pomerantz said. “And that’s the color that you see.”

Some parts of the glasswings’ chitin lacks pigments. And since the butterfly’s wings are paper-thin, you can see right through them to the other side.

By itself, the chitin that makes up the glasswing’s wings is shiny. And being shiny could spell disaster if you’re a butterfly trying to hide in a rainforest.

And that is what makes glasswings extra special. Their wings are transparent without being shiny.

The secret is a layer of waxy structures on the surface of the wing called nanopillars.

The nanopillars are incredibly small. They’re so small that researchers need a special type of scanning electron microscope to even see them.

The nanopillars look like miniature pointed towers made of clear wax sticking up from the surface of the wing.

“These structures are so small that they’re smaller than a wavelength of light. They’re just really, really, really tiny,” Pomerantz said.

Instead of having the wing’s surface be a flat, smooth, shiny surface, the nanopillars give it a rough texture.

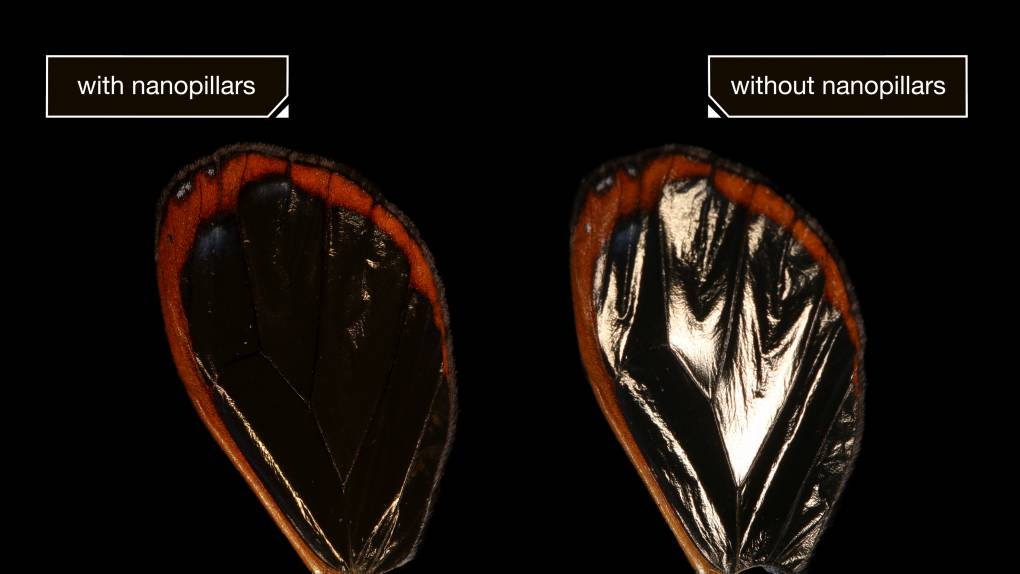

To show how effective the nanopillars are at reducing reflections, Pomerantz used chemicals to remove the waxy structures from a glasswing butterfly’s wing. The wing without nanopillars was much shinier than the one with the nanopillars left intact.

Pomerantz and the other researchers hope that what they learn about the glasswings might inspire new artificial anti-glare coatings.

“I think everyone can relate to light bouncing off their glasses or their phone screens and things like that,” he said. “We’re interested in bioinspiration — things that we’ve learned from nature, and applying it to our technologies and our products.”

By better understanding how these butterflies reduce glare, Pomerantz and the other researchers hope that technologies might arise to increase the efficiency of solar panels by reducing the amount of light that bounces off the surface of the panel before it can be turned into electricity.

“Nature’s already figured out solutions to many of the problems that we have today,” he said.