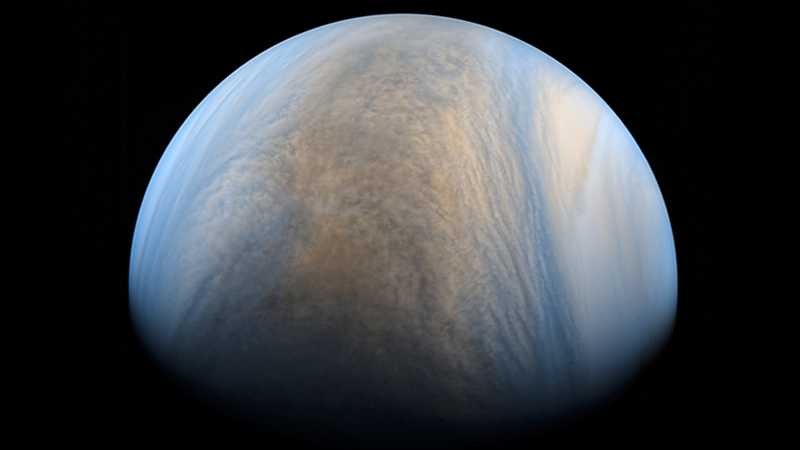

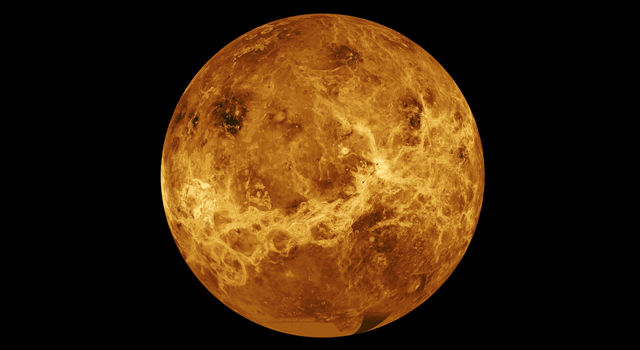

In an era of deep space exploration, a tantalizing and surprising discovery has raised the possibility of life on Earth’s nearest, scorching-hot planetary neighbor Venus.

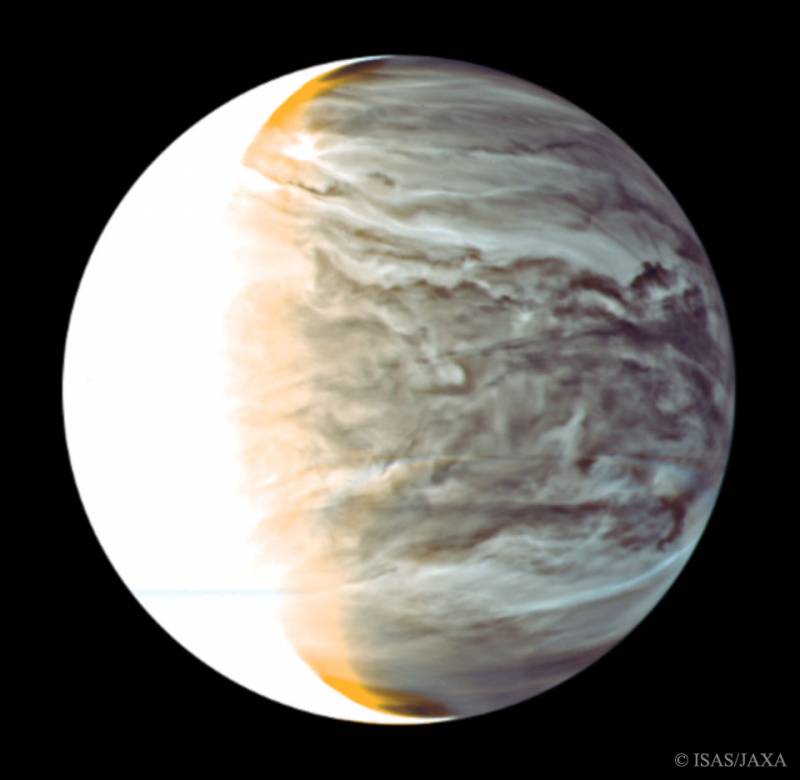

Scientists observing with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii detected the spectroscopic signature of the chemical compound phosphine in the Venusian clouds, about 35 miles above the surface. Follow-up observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile confirmed the discovery.

Phosphine, or PH3, a molecule composed of one phosphorus and three hydrogen atoms, is a “biomarker“ chemical that scientists hope to find in the atmospheres of distant Earth-like extrasolar planets to indicate possible biological activity.

On Earth, besides human industrial activity, the only known generator of phosphine is anaerobic life (which does not require oxygen to grow), either from microbial organisms or the decomposition of organic matter. And though there are nonbiological processes that produce phosphine deep in the hydrogen atmospheres of giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, those conditions are not found on small rocky worlds like Earth and Venus.

Follow the Phosphine?

Astrobiologists have focused their search for extraterrestrial life on places that harbor liquid water. NASA’s life-seeking motto is “Follow the water,” since life as we understand it on Earth requires water to thrive, let alone originate.

Orbital spacecraft like NASA’s Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and rovers like Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity, have raked the dry surface of Mars to find and analyze mineral residues from its extinct seas. Soon, Perseverance will dig for signs of past Martian life that may have thrived in those waters. The Galileo spacecraft and Hubble Space Telescope have revealed signs of an ocean hidden under the icy crust of Jupiter’s moon Europa, and the Cassini probe sampled plumes of mineral-laden water erupting from Saturn’s moon Enceladus, believed to originate from a subsurface sea.

But one thing we have learned about life on Earth is that it keeps showing up in places where we least expect to find it. “Extremophiles,” earthly organisms that thrive in some of the hottest, coldest and most toxic watery environments on our planet, have been found deep within frigid Antarctic and alpine lakes, around superheated hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean, and at the fringes of toxic geothermal hot springs. These highly resilient and adaptable life forms give us hope of finding signs of life in the waters of completely alien worlds.

With very little water vapor in its atmosphere, Venus is not a place where scientists expect to find signs of life, but the discovery of the biomarker phosphine is fueling further investigation and possible future missions to Venus to explore the question.