The silver lining of the appearance of different variants is that, for whatever twists evolution has thrown our way, the vaccines have largely been able to withstand them. Variants that have some capability to “escape” the immune response elicited by vaccines might cause breakthrough infections at higher rates, and their transmission might not be slowed as quickly. The shots, however, have maintained their incredibly robust ability to prevent sickness and severe outcomes from COVID-19.

But research into Delta has also underscored the importance of getting both shots of the two-dose vaccines. A study from Public Health England last month showed the Pfizer regimen was 88% effective at protecting against symptomatic illness from the variant, and the AstraZeneca vaccine was 60% effective — just slight drops in performance compared to other forms of the virus. But after just one shot, those figures plummeted to 33% for both vaccines. (The AstraZeneca vaccine has not been authorized in the United States.)

“After the second dose, we see the amount of antibody in a person’s blood is even higher than after the first dose, and therefore more people will be above a threshold,” Wendy Barclay, a virologist at Imperial College London, said at a press briefing Wednesday. “There’s a certain level of antibody and immunity you need to be protected. We know that’s a certain level for the Alpha variant, and there will be a slightly higher level required to protect against Delta variant.”

The Alpha variant Barclay referenced is also known as B.1.1.7 and first appeared last fall in the United Kingdom. Before Delta, it was the most transmissible variant and became dominant in a number of countries, including the United States, but does not have any meaningful immune escape prowess.

Scientists have estimated that Delta is perhaps 60% even more transmissible than Alpha. And in the U.K., it’s overtaken Alpha in frequency — which some experts have speculated could happen in the United States as well. The latest U.S. data indicate Alpha accounted for nearly 70% of sequenced cases, but Delta is amassing.

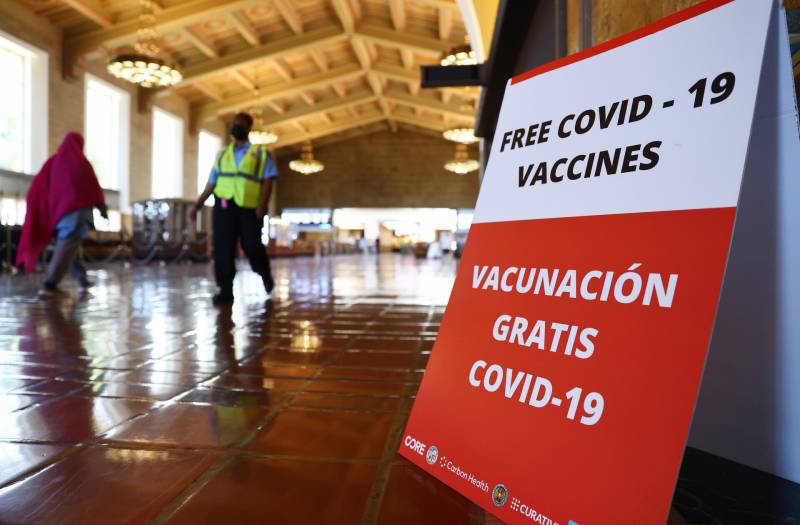

The urgency, then, is to get as many people immunized as quickly as possible, so more people are protected and there are fewer infections overall, as Delta increasingly accounts for more of the country’s cases.

“If you’ve had your first dose, make sure you get that second dose, and for those who have been not vaccinated yet, please, get vaccinated,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said at a White House briefing Tuesday, where he highlighted the threat of Delta.

There are several factors that appear to give Delta its transmission boost over Alpha. For one, Delta “can transmit more easily in a vaccinated population than the Alpha variant can,” epidemiologist Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London told reporters Wednesday. That advantage will become particularly noticeable in countries with higher vaccination coverage, like the United Kingdom and the United States, because Alpha will encounter greater barriers as it tries to spread. (It’s not that Delta can run rampant through vaccinated populations; it’s a matter that it can transmit comparatively more efficiently because of its immune escape capability.)

In fact, some experts anticipate that in the United States, variants like Delta, Beta and Gamma could start to claw away at Alpha’s dominance because they have greater abilities to spread among vaccinated populations, though the likelihood of that will depend on how many people remain unvaccinated. (Beta, or B.1.351, first appeared in South Africa, while Gamma, or P.1, emerged in Brazil.)

But Delta also appears to have some other advantages. “The virus itself is fitter in human airway cells,” Barclay said about what early research indicates. That means that an infected person will likely emit more virus into the air, and that the virus is more adept at infecting cells, so people need to be exposed to less of it to contract it.