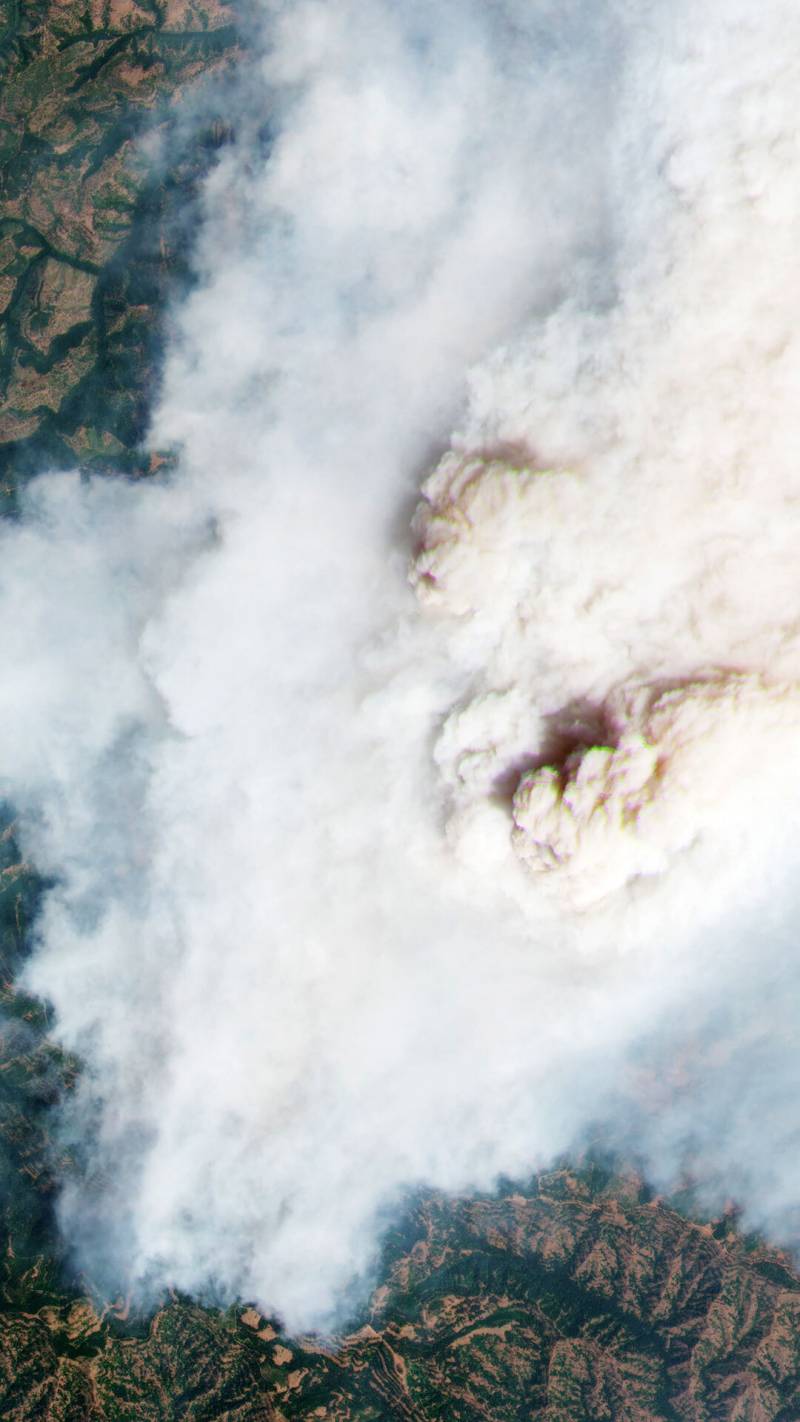

Two years of record dry winters and scorching early summer heat waves have primed forests across California to burn, just as the state heads into the hottest months of summer.

Fire season is here; fast, furious and early — exacerbated by dry conditions across most of the state, Paul Rogers, with the Mercury News, reported, writing that “memories of last year’s destructive fires are still fresh.”

“Remember, last year we saw the most acres burned in California as we’d ever seen in recorded history — 4.3 million acres burned,” Rogers said. “One out of every 24 acres of land in California burned last year. This year, like last year, it’s all about drought.”

And California is not alone, wildfires are ripping through forests, torching homes, and forcing evacuations across the Western U.S. The largest wildfire of the year has incinerated an area more than twice the size of the city of Portland and is still burning in southwestern Oregon.

Rogers and KQED’s Raquel Maria Dillon spoke with Brian Watt, KQED’s morning news anchor, about how the drought is exacerbating the fire season.

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Brian Watt: We’ve been told this fire season is already starting off worse than in previous years. Exactly how bad are we talking?

Paul Rogers: There’s good news and bad news. From January 1 to July 6, California had 4,922 wildfires on state, federal and private land. That is 720 more than we had a year ago over the same time period. The good news is those fires haven’t burned as many acres as we’ve seen in some previous years. They burned 83,000 acres — twice as much as last year during the same time period, but not any kind of record. The reason is because firefighters are on edge right now. They’re throwing all sorts of resources at these fires when they start. Lots of planes, helicopters, boots on the ground. So far, they’ve put most of them out pretty quickly.

Brian Watt: It’s really hard to imagine this fire situation getting worse. Walk us through what is making this fire season so dire.

Paul Rogers: I know a lot of folks have gone camping. And if you think when you go camping and you’re sitting there trying to start a campfire, everybody knows wet wood doesn’t really burn very well. But dry wood or dry brush burn very easily. And unfortunately, just about everything around the state right now is dry. And that’s because we’re in the worst drought that California has experienced in 50-years. San Jose experienced its driest year ever in 128 years of record keeping. It got about the same amount of rain — five inches — as Las Vegas or Palm Springs gets in a normal year. And the same in San Francisco, which experienced its third driest year since the gold rush in 1849. This is similar all across California.

Brian Watt: Add to that, climate change is making our heat waves hotter.

Paul Rogers: Which further dries out the soil and vegetation. And on top of all that, we’ve had about 100 years of fire suppression. Historically, when you look at forests throughout California, conifer forests up in the Sierra Nevada burned about every decade or two, naturally due to lightning strikes. Those fires cleared out dead vegetation. They left the forests with something like 40 or 50 trees per acre, and those forests were healthy. But after 100 hundred years of people putting out fires, we’ve now got up to 400 trees per acre in some places. The forests are unnaturally thick. They’re choked with dead vegetation. When they do burn, they burn hotter and out of control.

Brian Watt: Both of you talked to San Jose State researchers who are studying the dry conditions. What have they found?

Raquel Maria Dillon: Fire scientists are seeing lower vegetation moisture levels than ever before — well, since they started eight years ago measuring in the Bay Area. The researchers know this because they’ve been testing native plants that have evolved to survive and thrive in California. They snip off twigs from a bush called chamise at the same locations every two weeks. They measure that plant material to see how much moisture it holds. The issue is that in a fire, this kind of dry, semi-dormant vegetation becomes fuel for the flames. In firefighting, fuel is trees, grass, brush or buildings. And it’s one of the three sides of the triangle that firefighters talk about when they assess the risk of a major wildfire. The other sides are weather conditions and topography.

Brian Watt: What do these dry conditions mean for fire danger around the Bay Area?

Paul Rogers: Well, all places are not created equal when it comes to fire danger. There’s an area that fire experts call the wildland urban interface, or WUI, and that’s basically places where homes have been built right next to forests and chaparral, and other fire-prone areas. Those types of places are at particular risk. Think about communities in the East Bay Hills, where we had the historic Oakland Hills fire in 1991 that killed 25 people and burned nearly 3,000 homes, towns like Mill Valley up against Mount Tamalpais, towns in the Santa Cruz Mountains from Los Gatos all the way up to Boulder Creek, where the CZU fire burned a thousand homes last year and also all around Lake Tahoe. That’s a particular risk. It’s surrounded by forest and there are very few roads in and out.

Brian Watt: How are fire officials in the Bay Area getting ready for this, to respond to this elevated risk?

Raquel Maria Dillon: Well, it sort of depends on the jurisdiction and their budget. One example is in Berkeley, where the city is sending an extra $12 million to the fire department to prepare to improve emergency warning systems and clear more dry brush and other fire prevention projects. That money came from a ballot measure that Berkeley voters passed in 2020. Fire officials and elected officials are also begging homeowners to clear away vegetation around their homes. They say it’s a neighborhood effort and everybody has to be in it together because these neighborhoods have burned before.

Brian Watt: Anyone who has hiked in the East Bay Hills recently knows, it just feels dry out there. How exactly are the dry conditions affecting the forests in the region?

Raquel Maria Dillon: Yeah, it’s dry all over. In my backyard. In the forests and parks. The entire region is experiencing a tree die-off. Foresters with the East Bay Regional Parks District first identified dead or dying trees this spring. They don’t know exactly what’s causing this tree mortality, but it’s affecting all different kinds of species. It’s likely drought-related, but it could be bark beetles or a fungus.

At this point, it doesn’t matter to them. They’re focused on mitigation, and that means clearing away dead trees and brush and conducting controlled burns. But that kind of thing is expensive. The parks district in the East Bay has spent more than $5 million on vegetation management in the past couple of years. Now, their big goal is to expand prescribed burns, which is super complicated here because there are so many different jurisdictions that have a say in when and how they can burn. Plus, there are valid concerns about air quality. But fire officials are surprisingly hopeful because of the recent episodes of extremely bad air quality. The public is more open to prescribed burns than ever before.

Brian Watt: Paul, we’ve been hearing about prescribed burns and that controlled burns are actually key to restoring forest health and mitigating big fire. How is California doing with prescribed burns?

Paul Rogers: Not particularly well. The state has 100 million acres in total land area, about 20 million acres are forests that need to be thinned or cleared with prescribed fires. The problem is that you can’t do these kinds of controlled burns in the summer. They explode out of control. What you have to do is mechanical thinning. First, you’ve got to get out there with chainsaws. But there isn’t really much of a market for a lot of this dead wood. It’s expensive. It’s going to be a big job. California treated about 300,000 acres last year and needs to do about a million acres a year. It’ll take many years and billions of dollars to get this job done.

Brian Watt: Could we be coming up on a situation where we’ve got fire season, and then we’ve got prescribed burn season?

Paul Rogers: Yes, I think so.

Brian Watt: Prescribed fire season?

Paul Rogers: Prescribed burns work best when the ground is a little bit wet and you don’t have the risk of the fires getting out of control. Once officials do a mechanical thinning of an area, they have to come back with prescribed burns to keep the conditions right; that continues in perpetuity, when you live in an area with a Mediterranean climate that’s prone to fire.