After a four-year hiatus, El Niño is widely expected to make a grand reentrance this summer, ushering in the possibility of yet another wet, stormy winter.

“It looks like it’s full steam ahead,” UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain said in a live YouTube interview last week, in which he placed the likelihood of a strong El Niño event at greater than 50% — even as projections still vary widely.

“A strong event does have the potential for strong impacts on California,” said Swain.

The El Niño climate phenomenon — the opposite of La Niña — generally occurs every three to five years when ocean waters along the equator in the eastern Pacific warm by at least a half-degree Fahrenheit.

That, in turn, can reposition the jet stream and funnel storms toward the West Coast, often resulting in increased rainfall across thousands of miles, said John Monteverdi, emeritus professor of meteorology at San Francisco State University.

But a wet winter is not at all guaranteed, he said, noting that only one out of about six current models predicts a strong El Niño as this year progresses.

“People have been sort of charmed into believing that all El Niños mean storms,” Monteverdi said. “The historical record does not support a sure bet on that.”

Misconceptions about this mysterious weather pattern abound. Below are six of the most common ones.

Misconception 1: El Niño comes to California

Every time Jan Null reads a headline saying El Niño is coming to the West Coast, he cringes. The local forecaster, who founded Golden Gate Weather Service, said the headlines aren’t factual because El Niño actually occurs “about 3,000 miles away from California. It does not move en masse toward the California coast.” It can, however, greatly affect the weather in California.

Misconception 2: Every El Niño event and its effects are identical

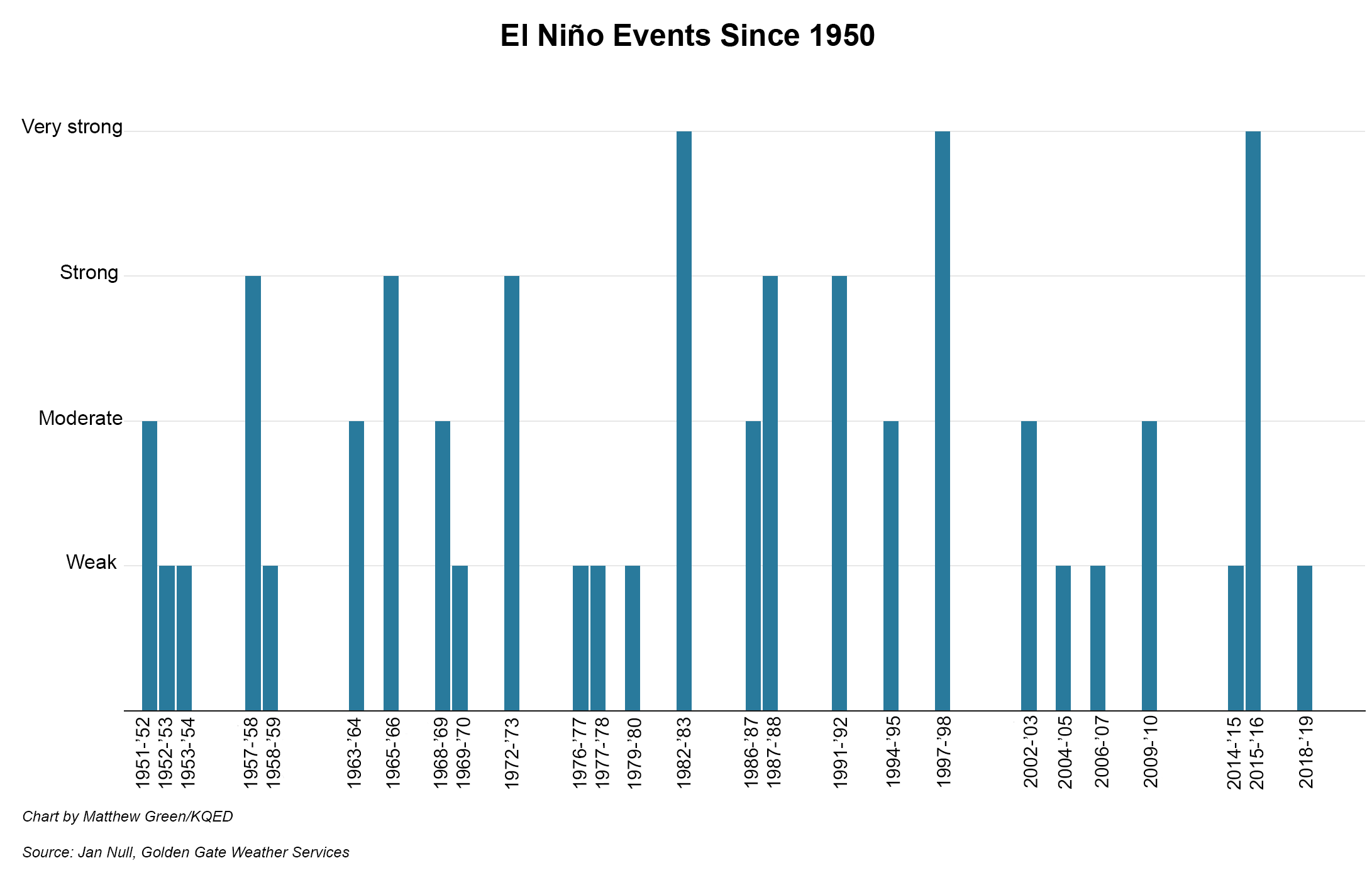

For the more than seven decades that El Niños have been tracked, their strength and impact have varied significantly, with many having little impact in California.

“The general notion is that El Niño brings wetter winters in California, although the relationship is somewhat fragile,” said UC Berkeley climate scientist John Chiang. “It’s really only the strong El Niños that affect rainfall over Northern California.”

And a slew of other oceanic and atmospheric variables can enhance or diffuse the effects of El Niño, noted meteorologist Null, saying, “I’ve often referred to it as the alphabet soup of all these other climate things going on.”

Misconception 3: El Niño is a storm

“El Niño is not a storm in and of itself,” Monteverdi said.

Rather, he explains, it is a phenomenon that can prime the atmosphere to push more robust storms toward the West Coast.

El Niños do “not spawn storms” and “do not directly create storms over California or anywhere else,” added Null.

Misconception 4: El Niños always result in catastrophic flooding

Significant flooding can just as likely occur in a non-El Niño period like the one Californians experienced this past winter (which was technically in a La Niña year).