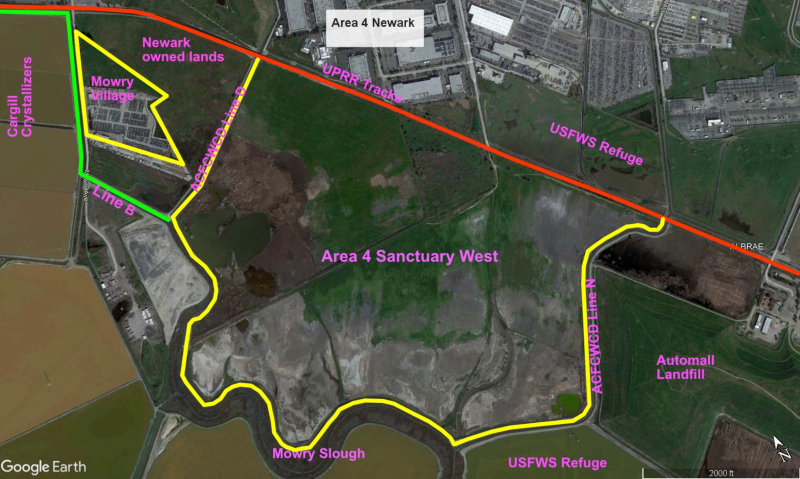

The acreage is currently home to a Pick-n-Pull auto-parts yard. If the developer wants to build houses on the land, it will require testing for contaminants and potential remediation. The site abuts a flood control channel and is next to another disputed housing project where developers have pitched the city on nearly 500 homes adjacent to a wetland near the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

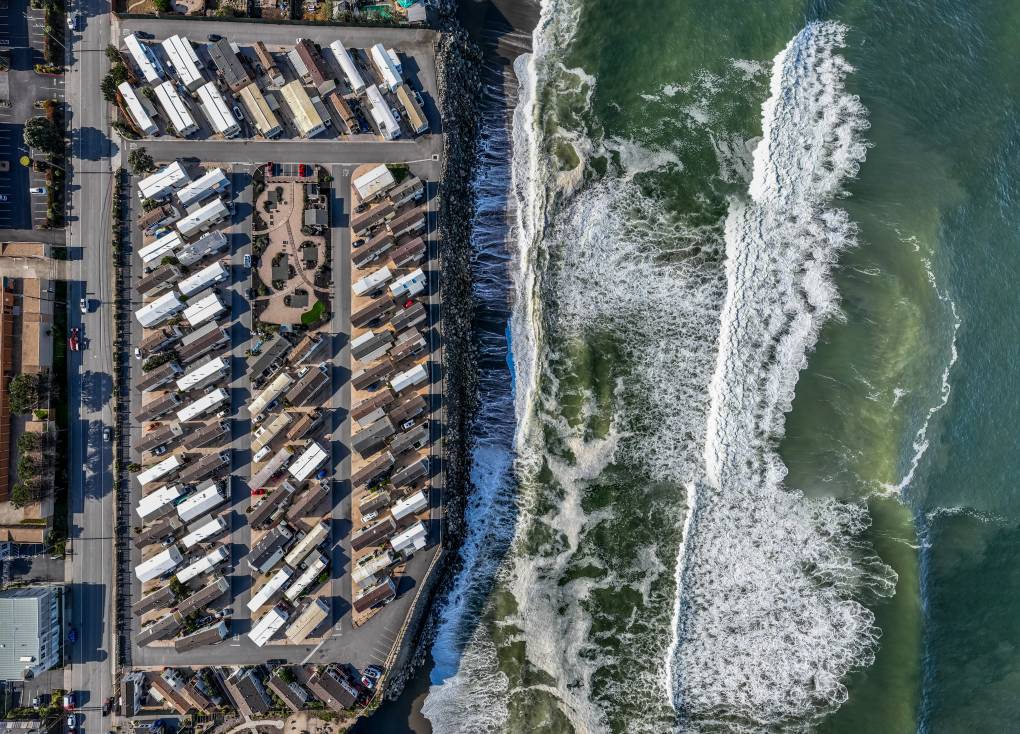

To avoid flooding from rising seas, Principal Evan Knapp said they plan to raise the grade of the entire housing community by about 14 feet and boost the entrance road up 13 feet with dirt brought in from elsewhere.

“We’ve tried mightily to make sure that we find commonality between environmental needs and development and provide some bridges to that,” he said. “This is one of those sites where when you start checking the boxes, it’s an overwhelming positive for the city.”

However, in a letter to city staff, the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board asked the developer to consider other sea-level rise impacts, like rising groundwater, which could infiltrate the homes decades before water would lap over the shoreline.

Due to the site’s proximity to San Francisco Bay, Katie Kulha, a senior water resource control engineer with the board, recommended the city require the developer to complete a vulnerability assessment for rising sea levels and groundwater.

Because of climate change, what happens here has ramifications on the entire region, said Jana Sokale, a Newark resident and member of the environmental group Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge.

“We need to harness the power of nature in whatever way we can to mitigate the impacts of burning fossil fuels,” she said. “People have yet to grasp that as sea level rises, these areas will drown.”

During a king tide event last January, water reached the property’s southern edge, and drone footage from the environmental watchdog group SF Baykeeper shows water permeating a small corner of it already.

“In 2050, these areas are going to be inundated most of the time rather than just four times a year at the biggest tide peaks,” said Eric Buescher, an attorney with the group.

Climate scientists describe wetlands as the best climate solution to protect the region from surging seas. Wetlands are sponges that soak up water. The more wetlands there are, the fewer sea walls or human-made adaptation projects planners must create.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for our generation to protect one of the few remaining marshlands that we have,” said Victor Flores, East Bay resilience manager for the environmental group Greenbelt Alliance.

Keeping the future climate in mind, Lynne Trulio, a San Jose State environmental studies professor, said instead of homes on these sites, the city could incorporate the land into the nearby wildlife refuge.

“There is not enough dirt to protect the entire Bay Area from sea-level rise to build giant levees when it really starts cranking,” she said. “Here’s a place where we wouldn’t have to do that because it has this topography that allows the marsh to move in.”

Other Newark residents like Nick Valencia — who is also worried about the looming impacts of climate change — support the project.

“If seas go up a couple of inches or even a foot or two, I think everybody in Newark is kind of going to be in a bad spot,” he said. “But I tend to trust developers in coming up with plans to mitigate those impacts.”

The Bay Area Council, a regional business association, supports the project to create middle-income housing for teachers, firefighters and other critical community members.

“Those people can’t afford to live in our communities, and it is outrageous that we would create a region as nice as the Bay Area and then say, ‘here’s the door’ to the people who are making that possible,” said Louis Mirante, vice president of public policy for the group.

Newark Mayor Michael Hannon said that he has yet to review the project formally and is waiting for city staff to present recommendations. Hannon said he is “not sure” if the project is good for the city.

“I certainly don’t want to approve a project that 20 years from now folks living in that project are concerned about their health and safety,” he said.

The city is also anticipating creating a sea-level rise resiliency plan, which Hannon said could inform whether shoreline housing like the Mowry Village project is safe.

“This is by far not a done deal,” he said. “We’re not blind or deaf to their concerns regarding rising sea levels. As information that may change that formula comes to us, we will certainly be looking at it and sensitive to that.”