San Mateo sea-level rise planners have proposed building an off-shore tidal lagoon from the southern edge of San Francisco International Airport to the northern tip of the city of San Mateo. They want to constrict it with an artificial barrier that would come with a series of doors — tidal gates that would close during big storms or high tides.

San Mateo County Proposes Off-Shore Doors to Combat Sea-Level Rise

The goal of the project is to protect Burlingame’s economic corridor — home to a slew of airport hotels, restaurants and tech companies like Meta — from future rising seas as well as inland flooding along half a dozen creeks that flow through the area toward San Francisco Bay, said Len Materman, CEO of OneShoreline, the county’s Flood and Sea Level Rise Resiliency District.

“Climate change will affect those ecosystems as the water level rises, and we want to create sustainable ecosystems that we can manage,” he said.

The idea is that operators would raise the doors when tides are high, or storms are intense to block water from running over the shoreline.

Still in its conceptual phase, the project resembles a system in Venice, where inflatable floodgates fill with air during high tides and storms. Materman said it could feature oyster beds that act like a reef and benefit the environment by creating a habitat for marine life.

The county could install a pump to control inland flooding from heavy rain storms. When the tides fall and the water recede, the operators lower the doors, allowing bay water to permeate the wetland area again.

One draft design includes an extension of the Bay Trail running over the tidal gates and a short living sea wall jetting out from the base.

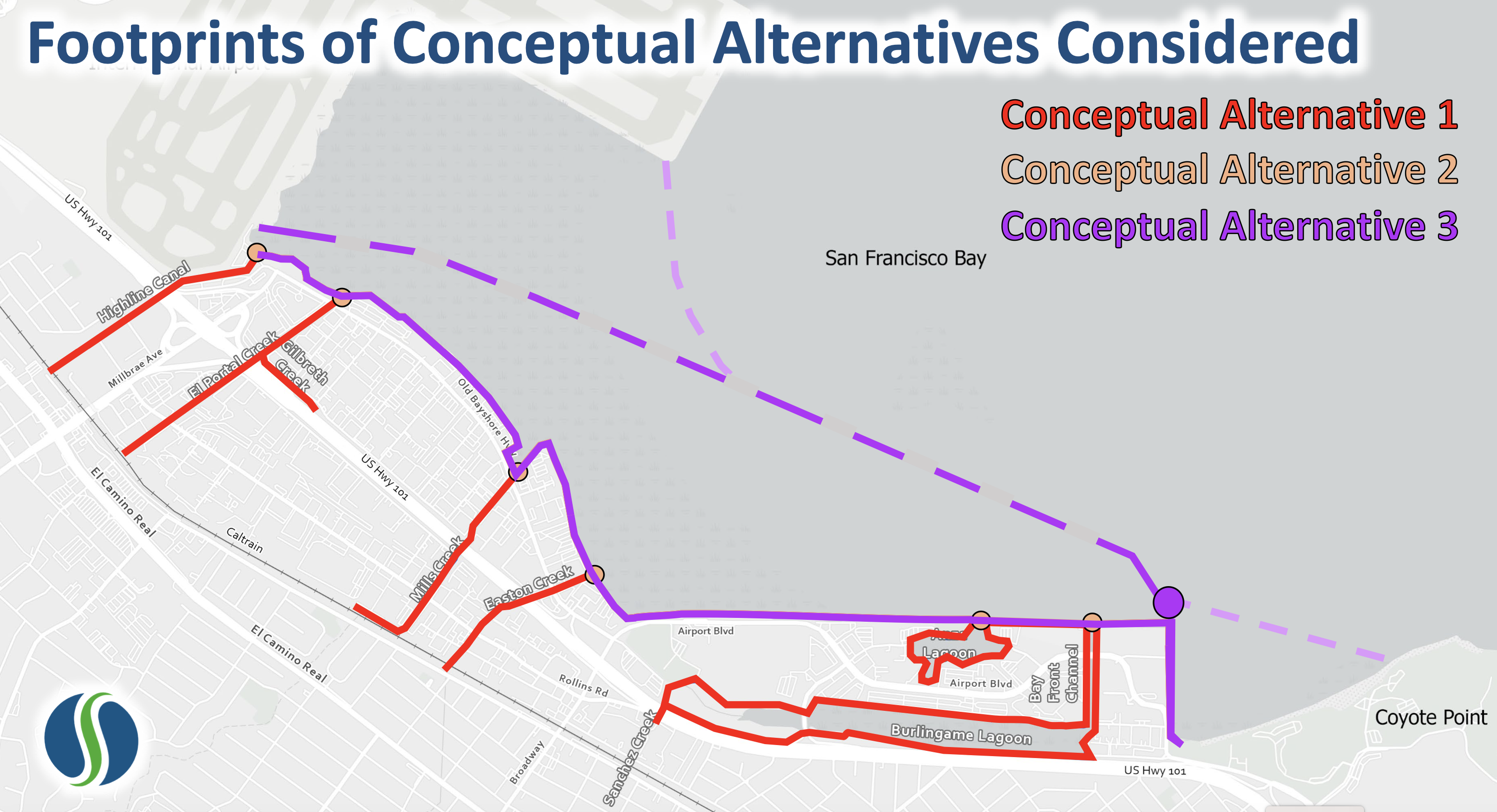

They’ve proposed building the nearly three-mile-long offshore barrier from Millbrae to Coyote Point within the city of San Mateo. At first, the tidal doors would be open 99% of the time.

As seas rise, the system would likely close more often, Materman said. Scientists project the San Francisco Bay could rise by a foot by 2050 — at which point the doors would close for an hour a day — and 3 feet by the end of the century, when the gates could close for up to 7 hours a day.

The county is currently studying the area’s adaptation options, including looking at the impacts and costs of the tidal door system.

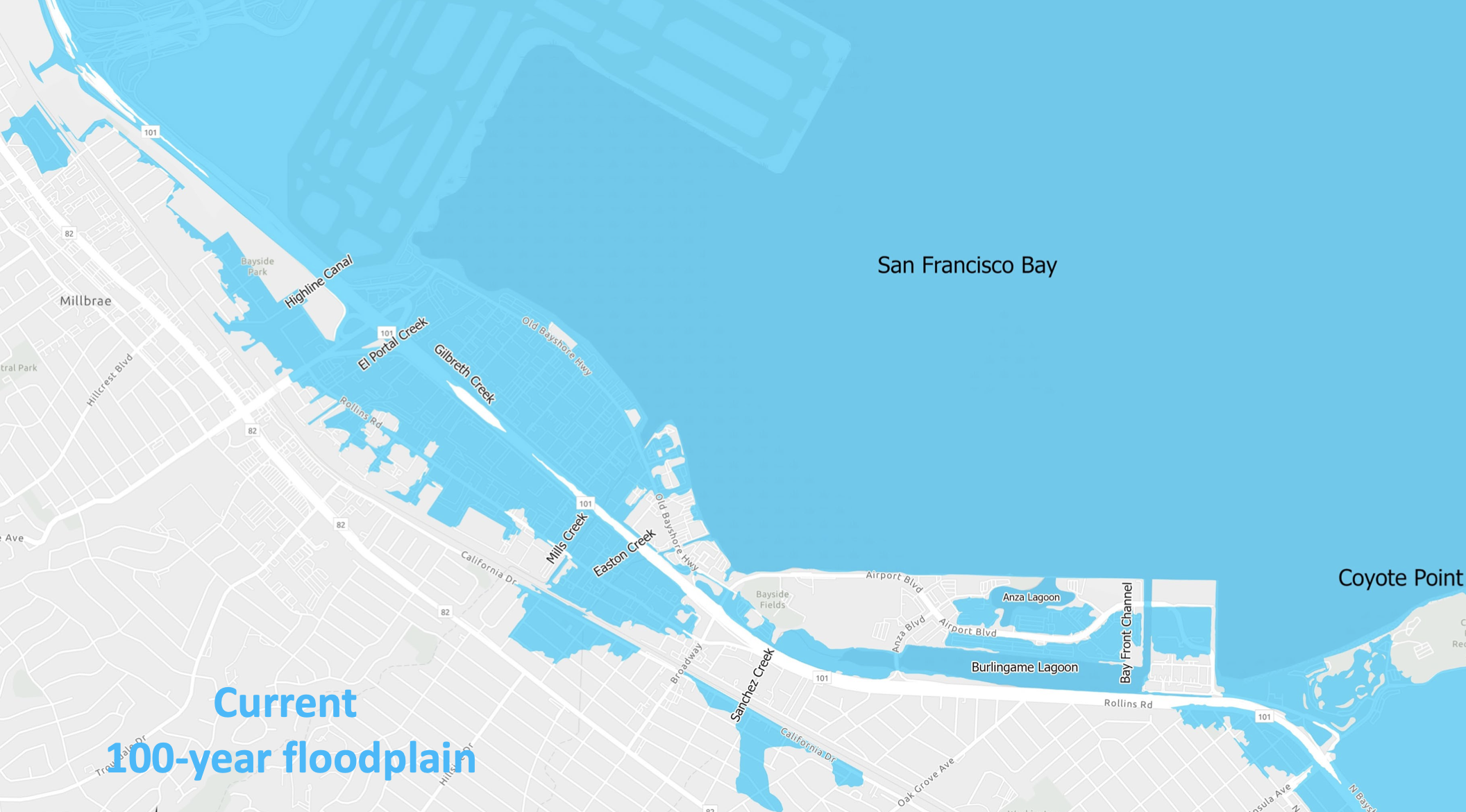

If the county doesn’t take action, Materman said rising seas could inundate much of this area, including parts of Highway 101 and Burlingame’s economic corridor filled with hotel branches like Marriott, Hilton and Embassy Suites. The area also has a waterfront dim sum restaurant, businesses like It’s-It Ice Cream and the software company Groupup. The estimated price of preparing San Mateo County’s shoreline is $11 billion.

A solution from rising bay water to stormwater

Materman said the tidal system would also give creeks room to drain during heavy rainfall and storms.

“It would be a win-win in creating capacity for stormwater [to drain and] to not cause flooding in areas along the bay,” he said.

San Mateo County will be the most at-risk California county from sea-level rise by the end of the century, with more than 40% of the county’s land at risk from rising seas, according to Materman. He said out-of-the-box ideas are needed to prepare for the slow-rolling climate impact. The county aims to adapt its 53 miles of bayshore for 10 feet of water beyond today’s high tide levels.

Materman said the project could remove much of the area from the Federal Emergency Management Agency flood zone.

Planners are also studying two more traditional alternatives: fortifying creeks and the shoreline with levees or building barriers along the shore with gates and pump stations at each creek.

“We’re going to need to do something along the shoreline that’s fairly dramatic from the old business as usual of just rebuilding a levee, which in the long term is not the best investment of our resources,” he said.

Syed Murtuza, public works director for the city of Burlingame, said the lagoon proposal would be less costly and intrusive than building levees.

“Close to one-third of our city revenues come from that area,” he said. “It’s very important to make sure the financial well-being of the city is protected from sea-level rise.”

But would it benefit the existing wetland?

Nícola Ulibarrí, a UC Irvine professor of Urban Planning who studies flooding and climate policy, applauded the ingenuity of the idea.

“I like the fact that it is flexible,” she said. “I think it’s a great design relative to options like a levee or a sea wall that will always be there.”

But Ulibarrí said that removing the area from the federal flood zone maps would be premature, given the pace and scale of climate warming causing rapid ice melt and sea-level rise.

“The problem is if this ever fails, suddenly you have even more development at risk, damage and even more lives potentially lost,” she said. “So, there’s this potential feedback loop where we put this in to protect people, but then long term, it might backfire.”

Elliott White Jr., a coastal ecosystem scientist at Stanford University, said the artificial lagoon could have unintended consequences.

As the doors closed more often as the sea rose, the gates would cut off the mudflat from the bay. In the long run, White said this would harm the ecosystem because sediment or dirt in bay water helps build it up. He said this could create a “sediment-starved” wetland that won’t keep up with the pace of rising sea levels.

“If you start with the premise that this is already an unhealthy ecosystem and you’re adding something that will reduce its resilience and that reduction is going to increase over time, then you’re effectively dooming that part of the landscape to never be a functioning ecosystem in the long term,” he said.

White points to Venice, Italy, where the inflatable floodgates fill with air during high tides and storms. The barrier is similar to the lagoon proposal in that it is flexible and responsive to weather and waves.

“In the Venice example, they’ve already greatly exceeded how many times they thought it would be open,” he said, recognizing that the gates have helped keep the city from flooding. “Now they have this very expensive structure operating at a capacity they never truly intended.”

John Callaway, a wetlands restoration ecologist at the University of San Francisco, agrees the project could negatively impact the remaining wetland habitat in the area.

“The longer the doors are closed, it has implications for water quality because if an area is diked off and not connected to the tides, it’s much more likely to be impacted by pollutants coming down and accumulating that then lead to algal blooms,” he said.

Callaway said he is also worried that when the doors are up, they will push the excess water elsewhere, “increasing flooding in other areas.”

“There needs to be coordination with other communities around the bay because if you just build a levee or a seawall, you’re just pushing sea-level rise into other communities,” he said.

Materman, with OneShoreline, said the proposal would allow them to manage a healthy lagoon and ensure the mudflats remain instead of being pounded by open water as seas rise.

“We’d rather manage a habitat for the shoreline than just add more open water to the bay,” he said.