Every grain of sand has a story to tell.

By studying the composition and texture of sand, geologists can reconstruct its incredible life history. “There’s just a ton of information out there, and all of it is in the sand,” said Mary McGann, a geologist at the United States Geological Survey in Menlo Park, CA.

McGann recently took part in a comprehensive research project mapping sand’s journey into and throughout San Francisco Bay.

Patrick Barnard, another USGS geologist who helped oversee the project, said that it will help scientists understand how local beaches are changing over time. In particular, Barnard wants to understand why beaches just south of San Francisco Bay are among the most rapidly eroding beaches in the state.

“It comes down to sand,” he said. “Where does the sand supply come from to these beaches, and is it being cut off?”

From 2010-2012, Barnard and his team sampled beaches, outcrops, rivers and creeks to track sand’s journey around the bay. They even collected sand from the ocean floor. The researchers then carefully analyzed the samples to characterize the shapes, sizes, and chemical properties of the sand grains.

Barnard said the information provides a kind of fingerprint, or signature, for each sample that can then be matched to a potential source. For example, certain minerals may only come from the Sierra Mountains or the Marin Headlands.

“If we’ve covered all of the potential sources, and we know the unique signature of the sand from these different sources, and we find it on a beach somewhere, then we basically know where it came from,” explained Barnard.

But sometimes this geological information isn’t enough.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to say where sand comes from,” said McGann. “Sometimes it’s distinct and comes from different watersheds and people know it. Sometimes it’s not obvious at all.”

McGann studies tiny ocean-dwelling organisms called forams and diatoms, which can provide additional information about how sand travels. Because these critters prefer to live in very specific environments, their location can offer clues about how ocean currents transport material.

McGann has found marine diatoms near Pittsburg, in Honker Bay, and ocean floor-dwelling forams near the Dumbarton Bridge. “They wouldn’t normally live there,” she said. “There’s no way those things would live there. It shows us that there’s a pathway.”

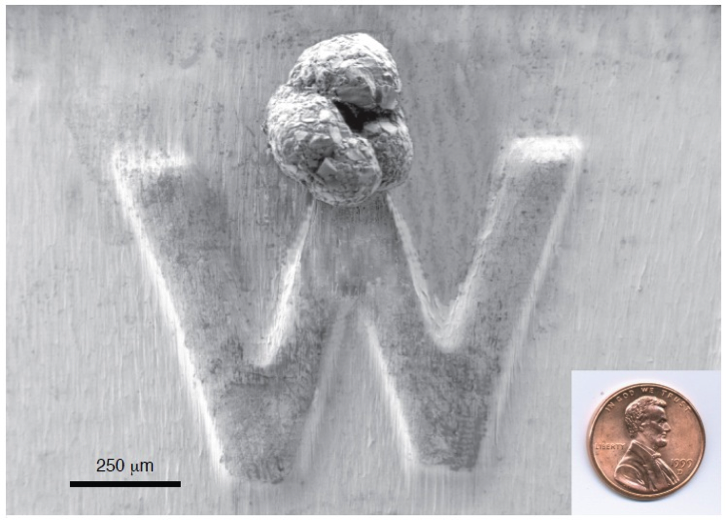

And those species aren’t the only things finding their way into the sand. Manmade materials can show up there, too. McGann has found metal welding scraps and tiny glass spheres (commonly sprinkled on highways to make road stripes reflective) in sand samples from around the bay.

“All of these things can get washed into our rivers or our creeks, or washed off the road in storm drains,” explained McGann. “Eventually they end up in, for example, San Francisco Bay.”

By piecing together all of these clues – the information found in the minerals, biological material and manmade objects that make up sand – the researchers ended up with a pretty clear picture of how sand travels around San Francisco Bay.

Some sands stay close to home. Rocky sand in the Marin Headlands comes from nearby bluffs, never straying far from its source.

Other sands travel hundreds of miles. Granite from the Sierra Nevada mountains careens down rivers and streams on a century-long sojourn to the coast.

In fact, much of the sand in the Bay Area comes from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, with local watersheds also playing an important role in transporting sand to the beach.

Barnard said he hopes this research will help Californians realize that the sand they enjoy at the beach has to travel through inland rivers and watersheds to arrive at the coast. By mining and constructing dams, residents could be cutting off sand sources and compromising the sustainability of local beaches, he said.

“Ultimately we’re potentially cutting off a supply of sand, which is what makes these beaches we enjoy wide to provide storm protection and recreational use,” said Barnard.

Although this project focused on San Francisco Bay, the same techniques could be used to study other coastal systems, he added, revealing the incredible life stories of sand from around the world.