There has been a lot of news lately about the bacteria living in our gut—the human gut microbiome. Researchers are learning which bacteria live there, who is naughty and who is nice and even a somewhat distasteful way to replace naughty with nice (a fecal transplant).

What gets lost in all of this is the fact that these bacteria are wild creatures whose only purpose is to divide and spread. If given half a chance, even those helpful bacteria would break free of the gut and spread through the body, eventually killing its host. To properly harness their power for good, we need to have ways to control them.

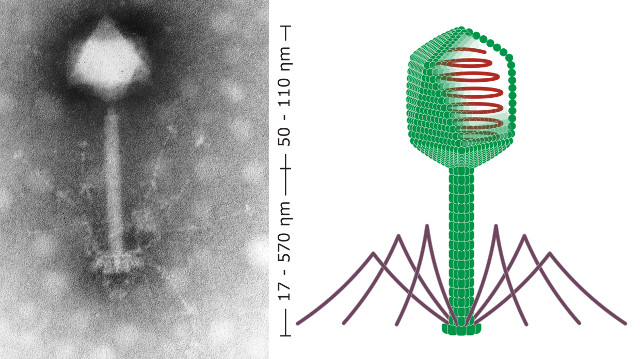

A new study presents an unexpected way that we work with viruses to keep bacteria confined to the gut. The idea is based on the fact that the mucous which lines the inside of our gut is riddled with viruses that infect and destroy bacteria (these viruses are called phages). If a bacterium gets too far into this mucous layer, it meets with a phage that destroys it. It is like a minefield of viruses set to explode whenever they encounter a bacterium. Except that it is even better than that…it is a self-renewing minefield.

When a phage infects a bacterium, it first hijacks the bacterium’s cellular machinery and forces it to crank out lots of new virus particles. Once the bacterium has made as many virus particles as it can, the bacterium then explodes releasing lots more phage into its surroundings. Now there are more phage that can infect any bacteria bold enough to venture where they shouldn’t.

This is a win-win for both the phages and us. We get to keep helpful bacteria confined to where they can do some good and the phage get a plentiful supply of bacteria. In fact, it is such a good deal for the viruses that they have evolved tails that can hook onto the ends of the mucin molecules in our mucous layer. This allows the viruses to linger for a longer time, increasing their chances of latching onto a bacterium.