How Mosquitoes Use Six Needles to Suck Your Blood

As summer approaches, we can look forward to picnics, hiking, camping and the mosquito bites that come with spending time outdoors.

It’s a good thing you can’t really see what that mosquito is doing when it bites — you probably wouldn’t want to watch as it buries six needles into you. But scientists have been figuring out all the bloody details. And it’s not just for idle curiosity: mosquito bites are more dangerous to humans than any other animal bite. While female mosquitoes — only females bite us — are drinking our blood to grow their eggs, they can leave behind viruses and parasites that cause diseases like West Nile, Zika, malaria and dengue.

An Anopheles mosquito bites into a human arm.

An Anopheles mosquito bites into a human arm.

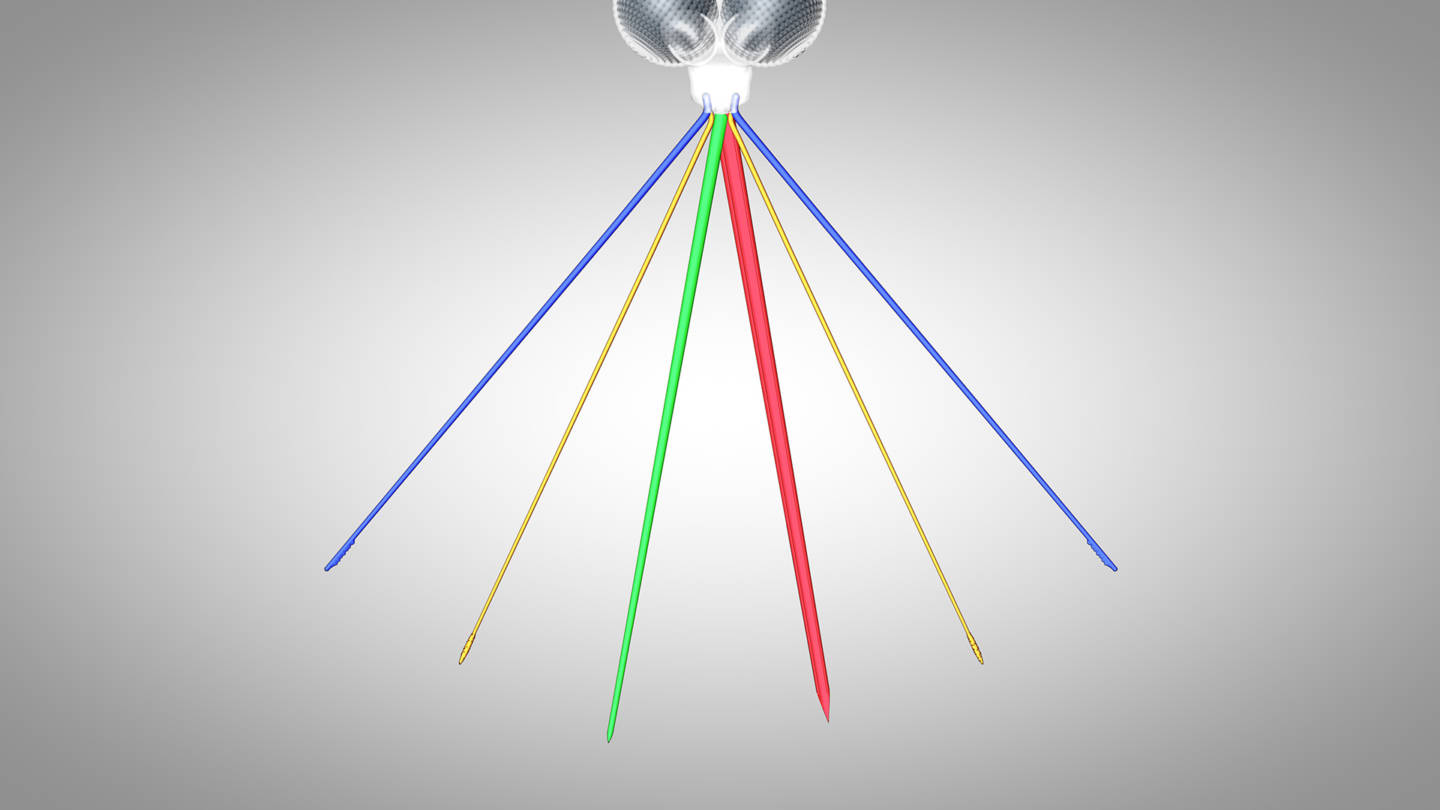

Part of what makes mosquitoes so good at getting humans sick, researchers say, is the effectiveness of their bite. Scientists have discovered that the mosquito’s mouth, called a proboscis (pronounced pro-BOSS-iss), isn’t just one tiny spear. It’s a sophisticated system of thin needles, each of which pierces the skin, finds blood vessels and makes it easy for mosquitoes to suck blood out of them.

Mosquitoes also have more than 150 receptors — proteins on their antennae and proboscis that help them find victims or figure out if the water is nutritious enough to lay eggs in. When malaria-causing Anopheles mosquitoes come out at night to look for blood, they track the carbon dioxide we exhale as we sleep. As they get closer to us, they detect body heat and substances called volatile fatty acids that waft up from our skin, said University of California, Davis, parasitologist and entomologist Shirley Luckhart.

“Why are some people more likely to get bitten than others?” asked Luckhart. “The volatile fatty acids given off by our skin are quite different. They reflect differences between men and women, even what we’ve eaten. Those cues are different from person to person. There’s probably not one or two. It’s the blend that’s more or less attractive.”

Researchers still haven’t figured out what about their volatile fatty acids makes some people more attractive to mosquitoes than others. What scientists have recently discovered is that once a mosquito’s proboscis pierces the skin, one of its six needles, called the labrum, uses receptors on its tip to find a blood vessel.

“Those receptors responded to the chemicals in the blood,” said UC Davis biochemist Walter Leal, whose lab made the finding. “Mosquitoes don’t find the blood vessel randomly.”

Instead, chemicals in our blood waft up like a “bouquet of smells” that guides the way — unwittingly, but surely — to our blood vessel. The labrum then pierces the vessel and serves as a straw.

UC Davis post-doctoral researcher Young-Moo Choo, in Leal’s lab, discovered a receptor by dissecting mosquitoes’ mouthparts and genetically testing them. Choo hopes his finding of this receptor, called 4EP, and the discovery of other receptors on the labrum, will help drug companies develop new mosquito repellents.

“First they’d need to find a repellent against the receptors,” said Choo. “Then they’d treat people’s skin with it. When the mosquito tried to penetrate the skin, it would taste or smell something repulsive and fly away.”

Scientists have been trying to figure out the anatomy of the mosquito bite for decades. It’s a job made difficult by the challenge of dissecting mosquitoes’ delicate mouthparts, which tend to fall apart in the hands of beginners. Choo attributed his dissecting abilities to his experience using chopsticks in his native South Korea. Video, powerful microscopes and genetic analyses have helped researchers figure out how the feeding system works.

When a mosquito pierces the skin, a flexible lip-like sheath called the labium scrolls up and stays outside as she pushes in six needle-like parts that scientists refer to as stylets.

Two of these needles, called maxillae, have tiny teeth. The mosquito uses them to saw through the skin. They’re so sharp you can barely feel the mosquito biting you.

“They’re like drill bits,” said Leal.

Another set of needles, the mandibles, hold tissues apart while the mosquito works.

In 2012, scientists at the Pasteur Institute in France filmed what happened once a mosquito proboscis had penetrated through mouse skin. The video shows the sharp-tipped labrum needle probing under the mouse’s skin, then piercing a vessel and sucking blood from it.

The labrum is shaped like a gutter. In order to become a straw it actually needs another mouthpart to lay over it. That mouthpart, called the hypopharynx, serves a dual purpose, as it also allows the mosquito to drool saliva into us.

When a female mosquito feeds, she separates the water from the red blood cells and squeezes it out through her rear end to make room for more blood.

When a female mosquito feeds, she separates the water from the red blood cells and squeezes it out through her rear end to make room for more blood.

As a mosquito’s gut fills up with blood, she separates the water in the blood from the red blood cells and squeezes it out through her rear end.

“She does that to concentrate the red blood cells,” said Luckhart. “The red blood cells provide a large protein component.”

By squeezing water out, she can fit five to ten times more blood inside her.

The sixth needle — called the hypopharynx — drips saliva into us which contains chemicals that keep our blood flowing.

“Your blood tends to coagulate immediately upon contact with the air,” said Leal. “They spit some chemicals so the blood doesn’t coagulate.”

Mosquito saliva also makes our blood vessels dilate, blocks our immune response and lubricates the proboscis. And it causes us to develop itchy welts, and serves as a conduit for dangerous viruses and parasites.

“Infected mosquitoes spit highly variable doses, anywhere from one infectious virion to 10,000,” said UC Davis virologist Lark Coffey, referring to virus particles. “The number of virions needed to productively infect mice can be as low as one. In theory, one might be enough to cause diseases like dengue or West Nile.”

It only takes eight to 20 early-stage malaria organisms to cause the disease.

“Within 20 minutes they make it to the human liver,” said Luckhart. “It’s a very fast process.”

The results of that speedy delivery are deadly. Malaria sickened more than 300 million people in 2015, and killed roughly 635,000, mostly children under the age of five and pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa.

“It’s probably an underestimate,” said UC Davis medical entomologist Gregory Lanzaro, “because reporting is terrible.”

Dengue fever, a disease transmitted by striped black and white mosquitoes called Aedes aegypti, is estimated to make almost 400 million people sick with jabbing joint pain each year, including a recent outbreak in Hawaii that sickened 260.

Scientists also believe that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are the main culprit for more than 350 confirmed cases of congenital malformations associated with the Zika virus in the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco. Since last October, an unusually high number of babies have been born there with small heads and a host of health problems like convulsions and persistent crying suspected of being caused by a Zika virus infection early in their mother’s pregnancy.

“We don’t yet know these babies’ life expectancy,” said Dr. Regina Ramos, who cares for these babies at the University of Pernambuco’s Oswaldo Cruz Hospital and participated via Skype in a symposium on Zika at UC Davis on May 26.

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes arrived in California in 2013, to the town of Clovis, near Fresno, and they’ve since been found in pockets throughout California, including Hayward and San Mateo. No locally transmitted cases of Zika have occurred in the continental U.S., though three babies with malformations associated to the virus have been born to mothers who contracted the disease elsewhere.

Mosquitoes don’t get anything out of making us sick ― they just incidentally pass germs onto us. In fact, researchers have found that some viruses started out as mosquito-only viruses. This isn’t hard to believe, as mosquitoes developed 200 million years before humans.

“As mosquitoes evolved the habit of drinking blood, some viruses have tracked that evolutionary path and become human-vectored viruses,” said microbiologist Shannon Bennett, chief of science at the California Academy of Sciences.

To reduce the chances of contracting a mosquito-borne disease, public health experts recommend wearing mosquito repellent, checking the screens on doors and windows and eliminating standing water inside and around our homes (.pdf). Mosquitoes lay their eggs in the water that pools in gutters and bits of trash, as well as in decorative ponds, potted plants, pet dishes and uncovered rain barrels.

“We’ve created the ecological niche that they’re well-adapted to,” said Bennett.