Everyone knows about the giant sequoia, California’s best-known endemic species—one that occurs nowhere outside the state. Not so many know about the blue oak (Quercus douglasii), but you see it whenever you leave the Central Valley in any direction. Blue oaks populate the dry hills all around the valley’s edge, starting as scattered specimens in the savanna and thickening with altitude into a proper forest. Higher up, they tend to give way to conifer forests. Their name comes from the bluish green of their leaves.

Blue oaks don’t make good timber and they don’t interfere with cattle, so the blue oak habitats have been surprisingly little touched by Western civilization. And the trees can live much longer than we’ve given them credit for.

“In fact,” says David Stahle, a tree-ring specialist at the University of Arkansas in a new paper on the blue oaks, “the remnant old-growth blue oak ecosystem may be one of the most extensive presettlement woodland cover types left in California.” Stahle’s paper in the journal Earth Interactions describes a large set of tree-ring records from blue oak populations that document California climate back to the mid-1300s.

Blue oak is a tough, drought-resistant tree that can shed its leaves when necessary. It also grows very slowly and doesn’t reach much more than 50 feet in height. A waist-high seedling can be 40 years old; a modest, scraggly specimen may have taken centuries to mature. Stahle’s team found a tree growing near Coalinga with 459 annual rings—and heart rot that had erased its earliest years. (Living trees are studied by extracting pencil-sized cores from their trunks.) They found another one, dead since 1884, with 553 rings. While that’s far short of the millennium-scale lifespans of the redwood, sequoia and bristlecone pine, it puts blue oaks among the longest-lived hardwood trees (angiosperms).

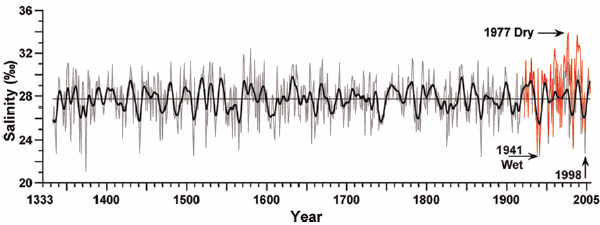

Blue oaks are sensitive to rainfall, putting on thick rings of wood in good years and thin ones, fractions of a millimeter thick, during droughts. Stahle’s team sampled over a thousand trees in 36 different blue oak populations (including one on Mount Diablo) to outline almost 700 years of rainfall in the Central Valley and Coast Range. The southernmost groves correlate well with Southern California rainfall. Analyzing separate rainfall records for northern and southern regions, the team documented periods when the large-scale weather patterns were shifted northward or southward. These in turn affect where atmospheric rivers, which dominate the winter rain totals, may strike coastal California. The north-south weather movements also affect water storage in Northern California, which supplies three-fourths of the water in the state’s aqueducts.