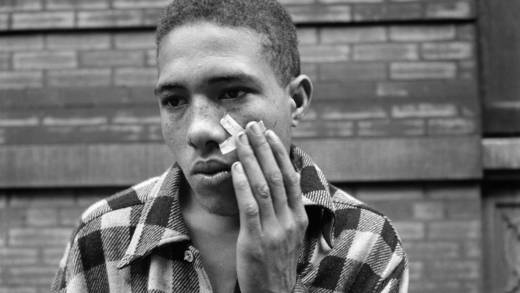

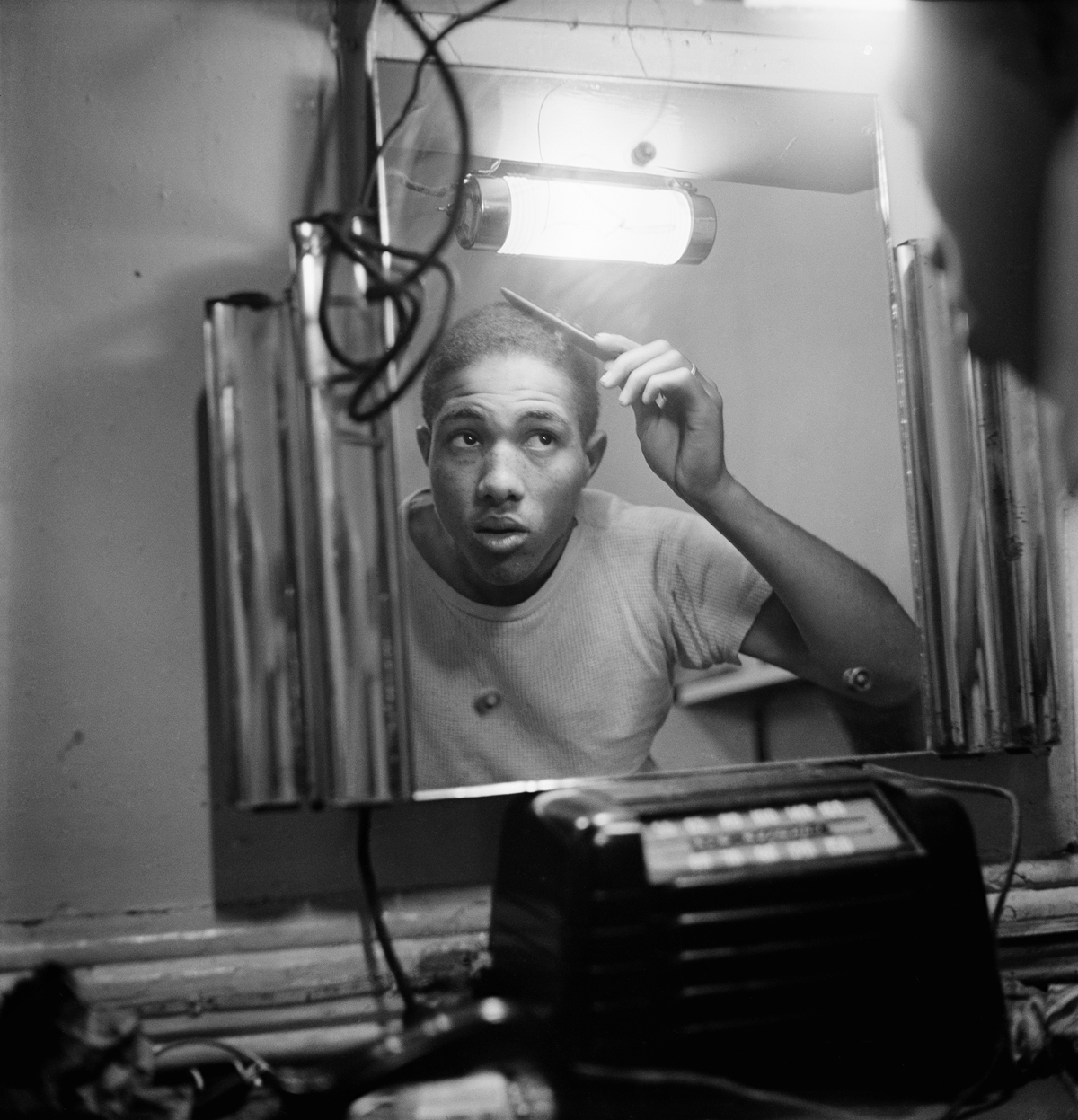

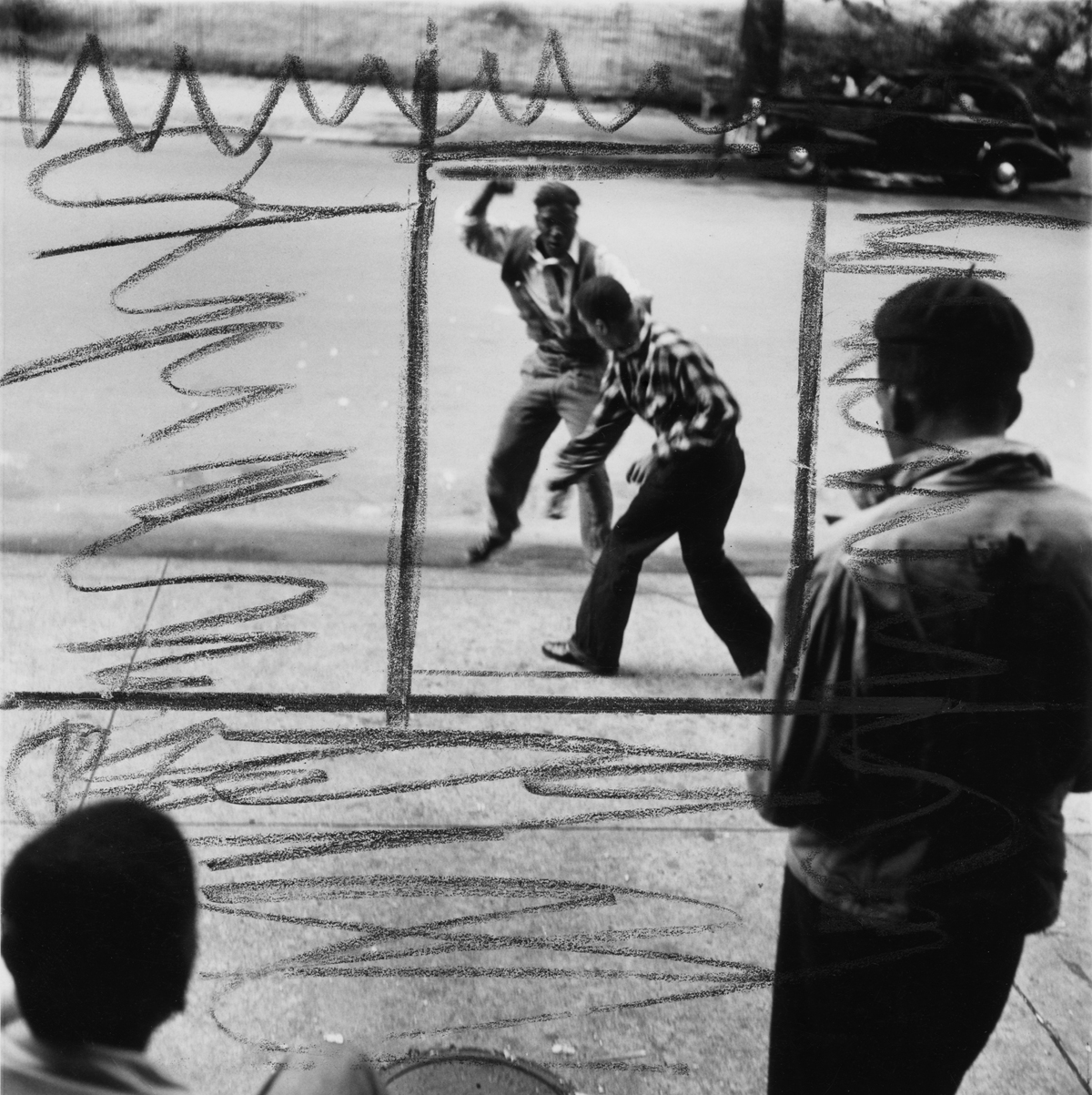

In 1948, Gordon Parks became the first Black photographer featured in Life magazine. Already a seasoned professional with work in Vogue and Glamour, Parks chose Life for a story he wanted to tell about Harlem’s gang wars after having spent some time in the systemically under-resourced borough. He found a subject in 17-year-old Harlem resident Leonard “Red” Jackson, leader of the Midtowners crew, and his story went on to be published under the title “Harlem Gang Leader.”

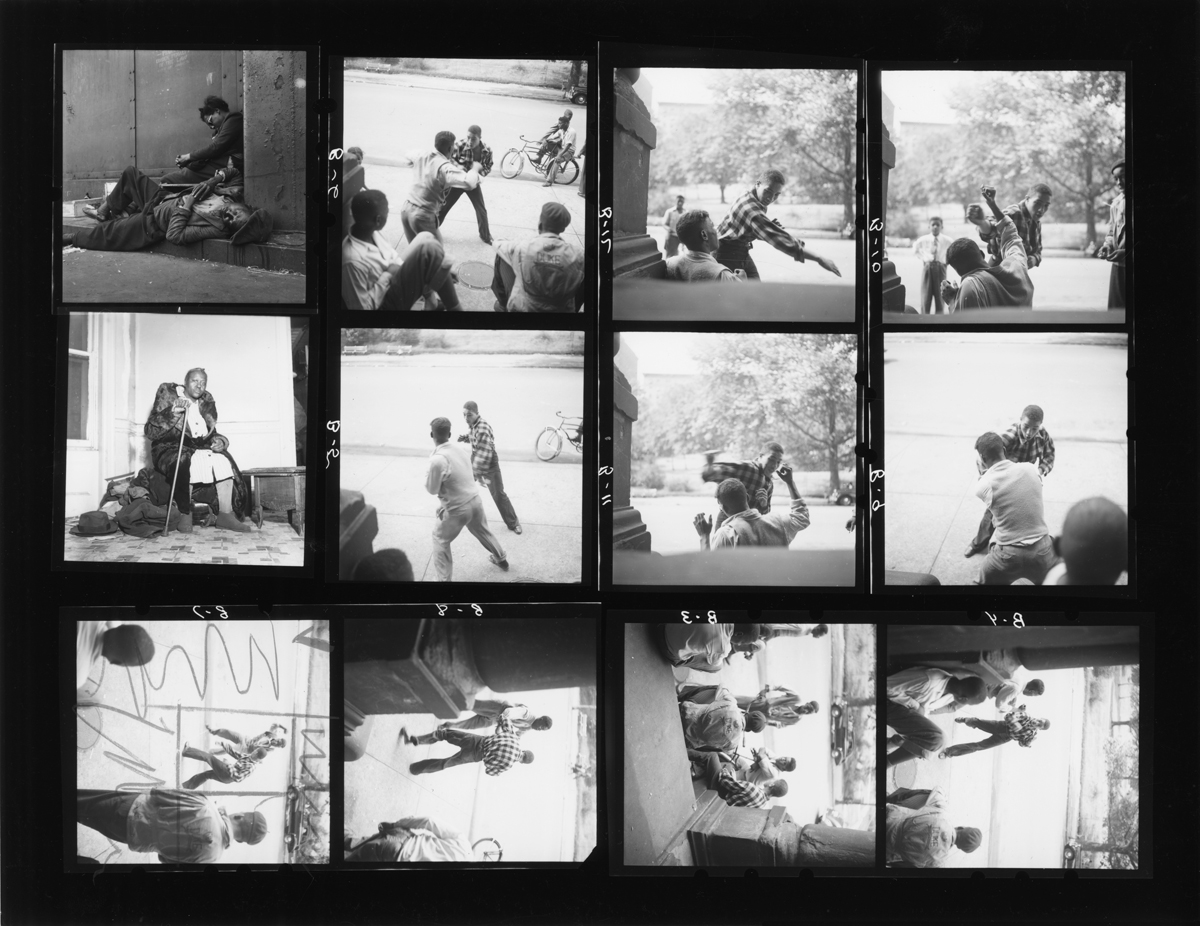

As was custom, Parks presented hundreds of negatives to his editors at Life, who in turn selected and edited 21 images from that collection to tell the story of Jackson and his friends. Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument, a touring exhibition making its final stop at BAMPFA, deconstructs the editorial process behind that photo essay while also proposing an alternative story about Jackson and his life in Harlem.

As a medium, photography carries implicit values of accuracy and impartial documentation. But there is a dangerous deceitfulness to still images — so much can be left unseen.

Russell Lord, curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art and organizer of The Making of an Argument, resists the notion of objectivity behind the photo essay. Instead, Lord presents a show that concentrates on the choices made by the editors at Life magazine: What biases might they have had towards the sensational and stereotypical? Why did they darken or crop images to distort Jackson’s appearance? Were these choices and the messages they relayed in opposition with Parks’ intentions — or, even more importantly, to the truth of Jackson’s life?

Through contact sheets covered with notes from editors, Parks’ unpublished photos, and additional context, the exhibit makes a strong argument for the presence of racial bias in Life’s “Harlem Gang Leader” story.

The first display in the exhibit features enlarged prints of the published photographs, laid out on the wall to mimic the magazine’s version of the story. Notably missing is the text that Parks provided to his editors. At a talk following the exhibition’s BAMPFA opening, Lord argued that this is in fact how most folks consume photo essays — primarily through images and without much input from words. There lies the show’s first argument: the visual story holds the most weight.