Over four weeks since a police officer killed George Floyd on video in Minneapolis, a nationwide reckoning with anti-Black racism is showing no signs of slowing. In the streets, protestors have participated in demonstrations of all sizes, including a student-led march of over 10,000 in San Francisco and 15,000 people marching for Black trans lives in New York. Online, people have created and shared innumerable resources on anti-racist action and how to break down anti-Blackness in non-Black communities.

This conversation has been especially prevalent in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community—for whom (now fired) police officer Tou Thao’s role in Floyd’s death exposed the deep-rooted ways Asians and Pacific Islanders have benefited from and contributed to systemic racism in America. For much of the last month, there’s been an uncharacteristic immediacy in the AAPI community to share content around dismantling the “model minority myth” and talks of returning to the Asian-Black solidarity of the 1960s. But in reality, these calls to action only scratch the surface of the long history of Asian identity in America.

To truly create sustained, long-term change for Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) in America, we as Asian Americans must go deeper: We must understand our own racial positioning in this country and deconstruct our desire to assimilate into whiteness. We must keep having conversations with family members who lack awareness or carry racist ideals. And, finally, we must recognize that we are all on our own unique journey to solidarity—and that we must work together to create the change we all want to see.

Do Research Beyond Social Media

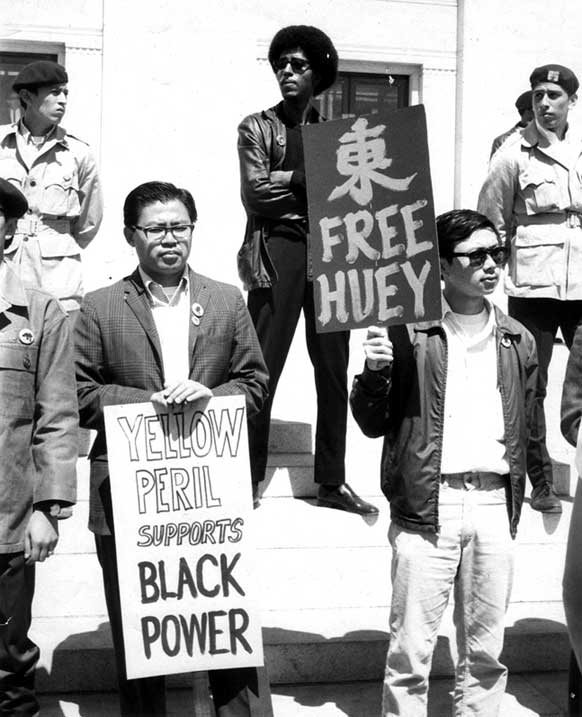

Social media can be an extremely useful starting point for learning about social issues. But a lot of these one-and-done posts, like ones with the slogan “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power,” make blanket statements that ignore the nuances that make the AAPI experience so difficult to unpack. While many people—myself included—first looked to the phrase as a symbol of Black and Asian solidarity, more information came to light about the slogan’s complicated history. In the ’60s, “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” had two primary purposes: Reclaiming “yellow peril” as a derogatory phrase against Chinese laborers in the 1800s, and showing support for the Black community.

But using the term today becomes more complicated after learning that Richard Aoki—one of the people who popularized the phrase at a rally for Huey Newton, and the only Asian American to hold a leadership role in the Black Panther Party—was revealed to be an FBI informant in 2012. Many activists today also take issue with the term, pointing out that the term “yellow peril” reduces the Asian American experience exclusively to East Asians while mistakenly equating Black and Asian struggles.

The “model minority myth” circulated by white journalists and politicians in the ’60s—which characterizes Asian Americans as a monolithic, law-abiding group that achieved success in America because of their cultural values—is another example of a flawed narrative to unpack. At a high level, we as a community understand how the “model minority myth” hurts us: It reduces the cultural and socioeconomic diversity of Asian and Pacific Islander subgroups to one and divides us from other minorities, like Black and Latinx groups. But deeper interrogation of the myth’s history shows just how deeply its stereotypes and principles have influenced the AAPI community today.