Two hundred and thirty people stepped up, and a man named Hiram Webb provided 60 muskets for them. Mr. A. J. Ellis was nominated as sheriff, and W. E. Spofford was made chief of police. On accepting the nomination, Spofford declared: “When I forget my duty, may God forget me.” He then organized volunteers into ten different police forces led by individual captains—Bezer Simmons was one of them.

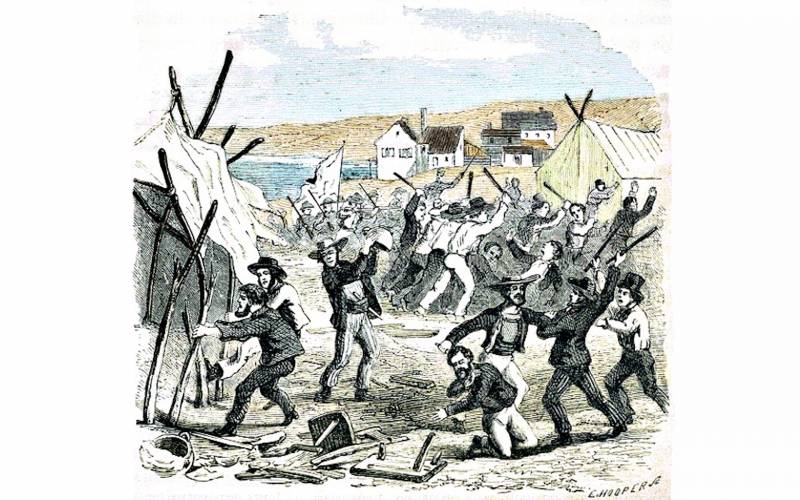

That same day, just 24 hours after the Hounds had attacked the Chilean encampment, 20 members of the gang were caught and locked up. That group included Samuel Roberts, who had been caught trying to escape to Stockton via schooner, and prominent gang member John Curley, who was apprehended in the Mission. The Hounds were held in a makeshift jail on board the USS Warren, a stores ship. (The only jail in San Francisco at the time stood at Clay and Stockton, and was notoriously easy to escape from.)

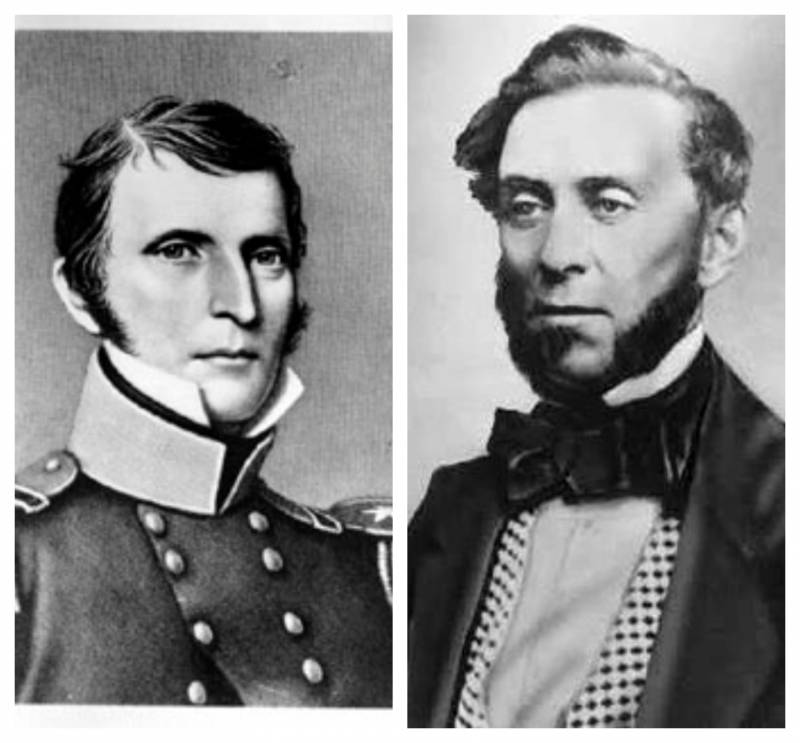

On Tuesday, July 17, the Hounds appeared before a grand jury comprised of three elected judges (Leavenworth, Ward and future senator, William McKendree Gwin) and a jury of citizens. The gang was charged with conspiracy, riot, robbery and assault with intent to kill. In his opening remarks, prosecution lawyer Francis J. Lippitt noted: “The charges… do not present the whole of the outrages… We have called it simply conspiracy to avoid technicalities.”

Bizarrely, one of the witnesses that testified was Leavenworth himself. As soon as the alcalde arrived on the stand, the Hounds’ defense lawyer vehemently objected. Leavenworth made matters worse by threatening to have the lawyer arrested. Another judge was forced to intervene in the subsequent melee, stating: “If the alcalde comes on to the stand as a witness, he must abide by the rules applicable to all witnesses and cannot, for the time, be considered a part of the court.”

In the end, Roberts was found guilty on all counts, and eight of his cohorts were guilty of one or more of the charges. All were sentenced to prison time with hard labor. Unfortunately, all escaped without punishment due to the lack of judicial infrastructure that plagued San Francisco at the time, as well as the influence of corrupt local politicians.

The trial did accomplish one thing, though. After the Hounds’ escape from formal punishment, its members were too afraid to regroup. Making their lives even more precarious was the fact that the city never forgot the atrocities the Hounds committed. It was later reported that, after the gang split up, some members sought work in the mines, only to be instantly recognized by those they had previously attacked. Several were hanged on the spot by revenge-thirsty miners.

While the meting out of official justice ultimately failed on this occasion, the swift process of capturing and removing the Hounds from San Francisco streets left many in the city convinced that the concept of organized policing could work. An Irish immigrant named Malachi Fallon was quickly called on to form a police force. “The merchants of the town having heard of my former connections with police matters, called to see me and offered inducements to remain and organize a police,” Fallon later wrote. “The council met and appointed me Chief of Police at a salary of six thousand dollars a year.”