The story of Jay DeFeo is often simply the story of her most famous work, The Rose. Made over a span of eight years, the monumental three-dimensional painting spent twice that time concealed behind a wall at the San Francisco Art Institute before it was rescued and restored by the Whitney Museum, where it now lives. The narrative arc of monomaniacal labor, the painting’s dramatic 1965 removal through a hole cut in the front of DeFeo’s Fillmore Street apartment and then, years after the artist’s death, a triumphant rediscovery, is very seductive. And there is no ignoring The Rose, neither its role in DeFeo’s personal history nor its physical presence. It is one of the greatest paintings I have ever seen.

But Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo’s Estocada & Other Pieces, a new book of essays and interviews by San Francisco curator Jordan Stein (organizer of Cushion Works), points out that The Rose was not DeFeo’s sole occupation during those eight years. She also painted on paper in her hallway—a “shadow Rose” called Estocada—in the six months leading up to her eviction. To think that DeFeo worked on nothing but The Rose is, according to Stein, “a mirage, reflecting history’s hunger for the monolithic and mythological.”

Resisting this, Stein’s own book refuses to be either monolithic or mythological. Between each chapter detailing the larger span of DeFeo’s life and work are stories of other hard-to-pin-down artists and their Bay Area ties: Trisha Donnelly, Ruth Asawa, Dewey Crumpler, April Dawn Alison, Lutz Bacher, Zarouhie Abdalian, Vincent Fecteau and Bruce Conner. These fragmentary glimpses into other artists’ approaches complement and bolster Stein’s detailed and often rollicking narrative of DeFeo’s art. She becomes not an aimless “lady in search of an encore” post-Rose (as one local newspaper depicted her), but a member of an iterative, vibrant and decades-long tradition of Bay Area art-making.

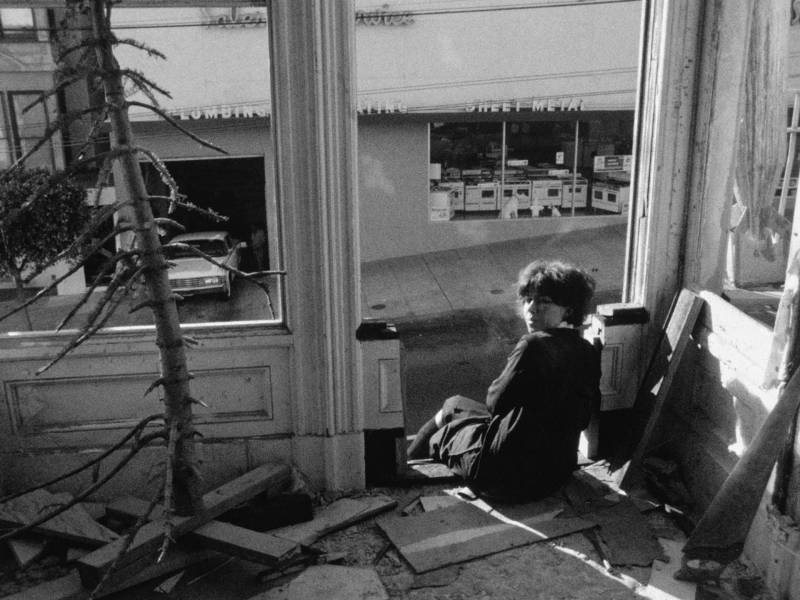

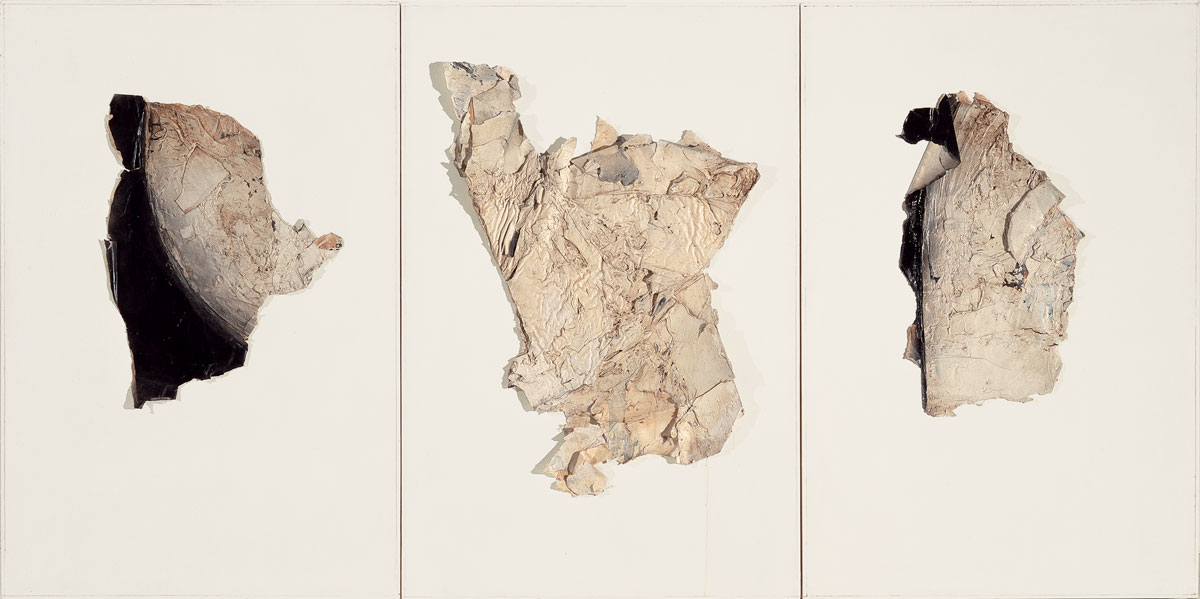

The structural through line of Rip Tales is the gradual morphing of Estocada (named for the final thrust of the matador’s sword through a bull’s neck). The large-scale painting on paper was taken from DeFeo’s apartment in pieces, ripped from the wall in “fleshy chunks.” (Stein’s language is surprising and fresh, casting even the very familiar in a new light. He describes The Rose as “a total piece of architecture resembling a distant nebula surrounded by dinosaur teeth or horse hooves.”)

Estocada followed DeFeo to a one-room cottage in Ross and a barn “studio” semi-open to the elements. It followed her to Larkspur, living under her bed, “rogue and untethered” until it began to appear in photographs, first in a color image from 1971, then in a series of gelatin silver prints from 1973. A trio of large Estocada fragments, rescued from the trash and mounted to masonite, achieved some stasis in Tuxedo Junction (1965/1974). Meanwhile, DeFeo’s photographs continued to morph—into collage materials, photocopies and even more photos. One way the story of Estocada ends, Stein says, is in an imageless photograph, a collaged, irregular shape of exposed photographic paper.