You can listen to this episode of the MindShift Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, NPR One, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Mental health has only become more important and more fraught as the pandemic has confined children to their homes and limited their social interactions. With parents losing jobs and COVID-19 claiming loved ones, adolescents are experiencing a lot more strain on their mental health.

“There’s just a lot more worry about everyday things. So there’s anxiety about things – and I’m not talking necessarily diagnostic anxiety. I’m just talking about the result of living in a really chaotic, stressful world,” says Tracy Smith, director of the Wright Institute’s School-Based Collaboration, a clinical psychology program that connects therapists in masters and doctoral programs with schools in the San Francisco Bay Area.

According to Smith, middle-school-age students experienced anxiety about general safety and whether they’re communicating with their peers enough, whereas high schoolers are stressed about family security and took on more responsibilities like childcare or jobs outside of school.

There are ways, however, that schools can try to ensure that children can get their needs met when they are struggling and be proactive about maintaining their mental health and wellbeing. Long before the pandemic, educators at Urban Promise Academy (UPA), a middle school in Oakland, California, started offering their students therapy services through a partnership with the Wright Institute to address mental health concerns. UPA’s students faced things that many adolescents experience, like anxiety, trauma and self harm. Although UPA uses social and emotional learning and counseling that’s common in many schools, they benefited from having therapy services that offer individualized and hands-on support tailored to each student. With a few big adjustments, they continued to support students’ mental health even when they were no longer in school buildings.

Cultivate a Positive School Culture

When UPA first opened in 2001, the founders, including current school counselor Mary Ellen Bayardo, wanted to create a school that responded to students’ needs and focused on student mental health. Bayardo worked to destigmatize mental health care by giving counseling and support services a strong presence at the school. Outfitted with plush chairs and blankets, her counseling office is a comforting space where students are encouraged to drop in with any concerns. “When you have that kind of environment, you really get all the information you need to be able to really match the services to the kid,” says Bayardo.

School environments are complex and one solution rarely solves all problems. Additionally, people often overlook how schools can be sites of trauma and the attention is usually focused on addressing the trauma that children “bring to school.” For UPA, school culture was as important as the services themselves. “If a school is iffy or mixed about how important mental health is to education, we have a harder time,” says Smith about how schools must normalize mental health care to make therapy services more effective.

Getting Help

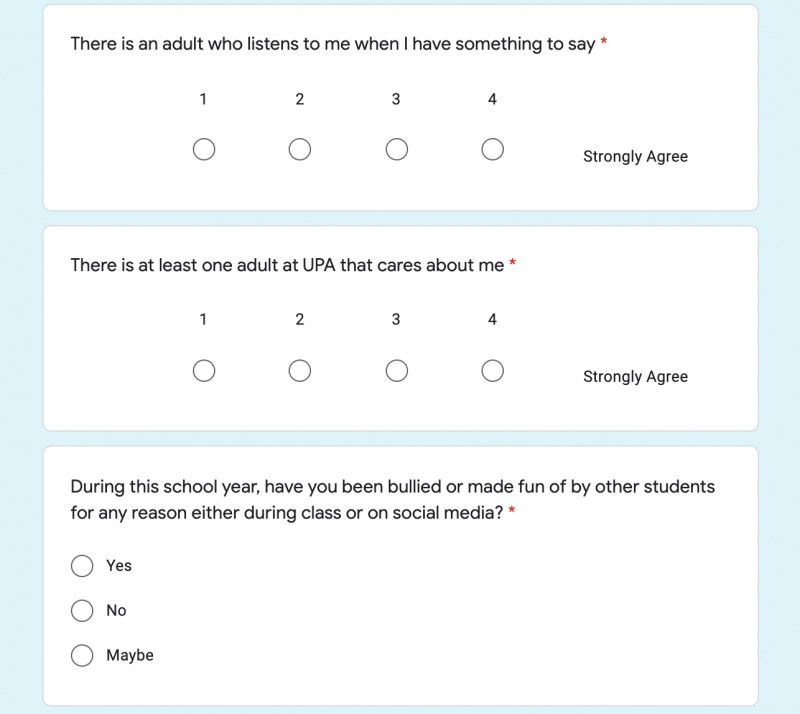

Strong relationships with teachers is a priority at UPA because teachers are instrumental in noticing signs that a student might be in need of support. Research shows that it’s important for children to have at least one trusted adult in their life. “We’ve had strong leadership and because we have teachers that stay for years and years, this is what’s built up: that core of resiliency, that core of safety and stability,” says Bayardo.