Russell opined that the sooty shearwaters, which fly tens of thousands of miles around the Pacific basin each year, became confused by a thick fog and flapped in a blind panic toward lights onshore. Others thought the sound of gunfire from the Army's Fort Ord might have spooked the birds.

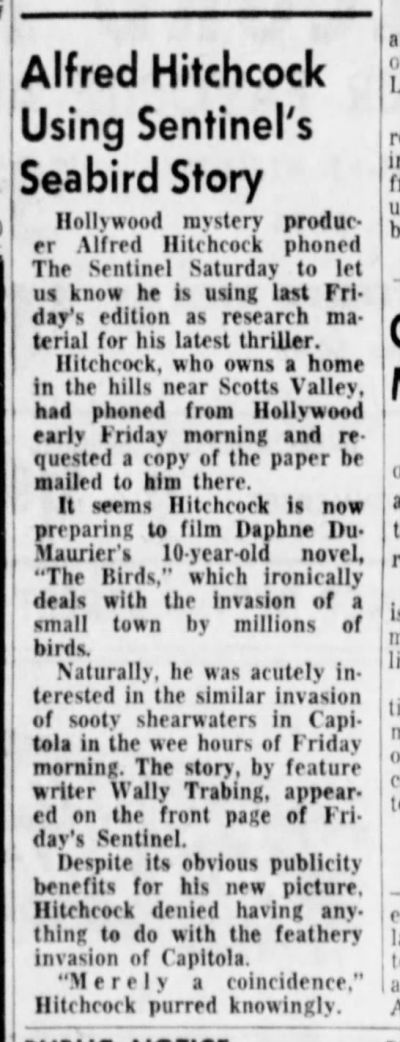

One of those who took note of the sooty shearwater episode was movie director Alfred Hitchcock, who owned a 200-acre estate at the end of a narrow, winding road in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Three days after the invasion, the Sentinel buried an item on page 4: Hitchcock had read the paper's account of the invasion and planned to use it in his adaptation of the Daphne Du Maurier short story "The Birds."

And in fact, the Santa Cruz incident and Ward Russell's theory both made it into Hitchcock's final script, set in Bodega Bay. In the film version of "The Birds," Mitch Brenner, the character played by Rod Taylor, is trying to think of a way to drive away flocks of crows and gulls that have begun terrorizing the locals. Brenner has the following exchange with several other characters and a bird sympathizer identified only as Mrs. Bundy:

Mitch: Mrs. Bundy, you said something about Santa Cruz. About seagulls getting lost in the fog, and heading in for the lights.

Deke: We don't have any fog this time of year, Mitch.

Mitch: We'll make our own fog.

Sholes: How do you plan to do that?

Mitch: With smoke.

Malone: There's an ordinance against burning anything in this town, unless it's...

Mitch: We'll use smoke pots. Like the Army uses.

Deke: What good'll that do? Smoke's as bad as birds.

Mrs. Bundy: Birds are not bad!

Sholes: How can we go on living here if we blanket the town with smoke?

Mitch: Can we go on living here otherwise?

For decades, there was no better explanation for the the 1961 Santa Cruz bird mystery than they'd gotten lost in the fog.

But in 1991, a clue appeared. Hundreds of brown pelicans and cormorants were found sick or dead along the Monterey Bay shoreline. Veterinary researchers eliminated viruses, bacteria or heavy-metal poisoning as the cause, then determined the birds had suffered acute poisoning by domoic acid. The toxin was found both in anchovies the birds had fed on and in plankton the fish had consumed.

UC Santa Cruz marine biologist David Garrison studied the 1991 incident and speculated several years later that domoic acid might have been responsible for the 1961 bird invasion. It wasn't until 2012, more than half a century after the episode, that researchers from UC San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography found direct evidence that the sooty shearwaters had indeed suffered domoic acid poisoning.

The Scripps scientists used an archive of biological samples from California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations, a marine monitoring program in operation since 1949, to try to investigate the conditions the birds would have encountered in Monterey Bay in the summer of 1961. Specifically, the team was looking for samples that might show the presence of Pseudo-nitzschia, a genus of diatoms that includes species known to produce domoic acid.

In a summary of the research published in Nature Geoscience, the Scripps oceanographers reported that Monterey Bay zooplankton collected in 1961 showed high levels of the toxin-producing diatoms. Here's the mildly worded conclusion to the Scripps team's findings:

Given the similarities between events in 1961 and the domoic acid-induced poisoning of 1991, we suggest that toxic Pseudo-nitzschia were probably responsible for the odd behaviour and death of Sooty shearwaters in August 1961. This brief study therefore supports the contention that domoic acid caused the seabird frenzy ... and strongly suggests that domoic-acid-producing phytoplankton have been an agent of marine animal mortality in the California Current system for at least the past fifty years.

OK -- maybe not quite Perry Mason stuff. But case closed.