The Booker T. Washington Hotel in St Louis, the Off-Beat Restaurant in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and Clifton’s Cafeteria in Los Angeles are among the forgotten Green Book sites.

Many remaining buildings in places like Albuquerque sit abandoned in now poverty-stricken neighborhoods. Others have been demolished or transformed into other purposes.

Decommissioned as a U.S. highway in 1985, Route 66 still holds lore as a road where Americans ventured West. The 2,500-mile highway passed through eight states, connecting tourists, mainly white, with friendly diners in welcoming small towns. Nat King Cole famously sang “(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66” in a 1946 hit.

“The irony is that Nat King Cole wasn’t welcome in most motels on the Mother Road,” Taylor said.

African-Americans taking vacations along Route 66 had to plan detailed itineraries to avoid potential violence in “sundown towns” — places that worked to exclude blacks with intimidation and segregation laws. Black travelers often brought along portable toilets, since many restrooms along the highway excluded them.

“That’s a whole other experience of traveling Route 66 that doesn’t really get talked about in popular culture. Instead, it’s conveyed as the open road to freedom and adventure,” said Katrina Parks, a documentary filmmaker who worked on the “Women on the Mother Road” project. “While that’s certainly true, there’s also this other side that it could also be a threatening place, depending on your race.”

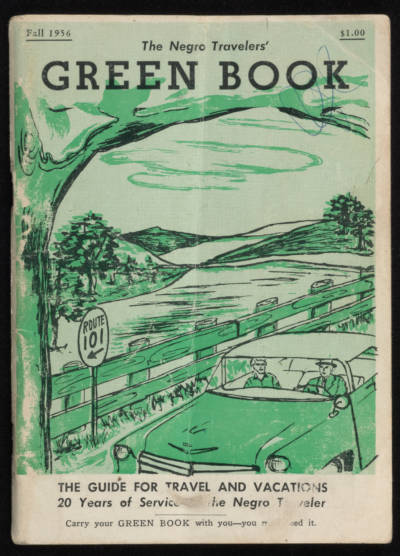

Taylor said she never would have heard about the other part of Route 66 had she not stumbled upon a Green Book during her research for another book about the highway. The Green Book, published from 1936 to 1966 by Harlem postal worker Victor H. Green, offered black travelers tips on places to visit and eat while on the road.

“Carry your Green Book with you,” the book warns readers on its cover. “You may need it.”

A 1949 edition promised to “give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable.”

Jewel Hall, 84, traveled down Route 66 and other U.S. highways with her late husband, Fred, during the 1950s. The Rio Rancho woman and her husband rarely went on road trips without the Green Book.

“Restaurants? Our restaurant was our car when we didn’t have that book,” Hall said. “Sometimes you didn’t dare stop. You didn’t know what to expect.”

But when black travelers found a friendly place, thanks to the book, they would come in contact with other black travelers and felt as if they were among family, Hall said. Businesses were usually black-owned or operated by sympathetic whites, she said.

Despite the image of the American West being more welcoming for African-Americans, the Green Book was still needed past Oklahoma.

One place that did admit blacks was Albuquerque’s De Anza Motor Lodge, a business owned by Zuni trader and Indian art collector Charles G. Wallace. The motel, decorated with American Indian murals and coupled with a cafe, was a popular spot for writers and artists along post-World War II Route 66. Black motel guests could catch a nearby show with American Indian and Mexican-American doo-wop singers.

Today, the De Anza is boarded up and has been the target of a redevelopment project by the city of Albuquerque that seeks to save the building.

Taylor said other cities and towns should recognize former Green Book spots as culturally significant sites. By acknowledging the businesses, towns can better understand their role in civil rights.

“The places (black travelers) were navigating were really hostile. You have to remember that,” Taylor said. “So, the idea of vacationing for blacks was already a statement of purpose … almost resilience.”