The 1971 San Fernando (Sylmar) earthquake killed 64 people, buckled roadways and leveled scores of buildings. Soon after, California passed a law that requires updated mapping of major earthquake fault zones.

But due to a lack of funding, the effort ground to a halt not long after it began and resumed only about four years ago.

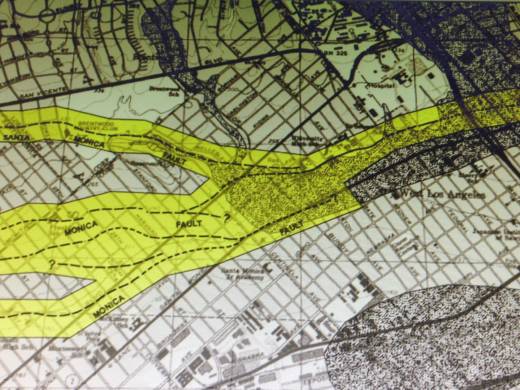

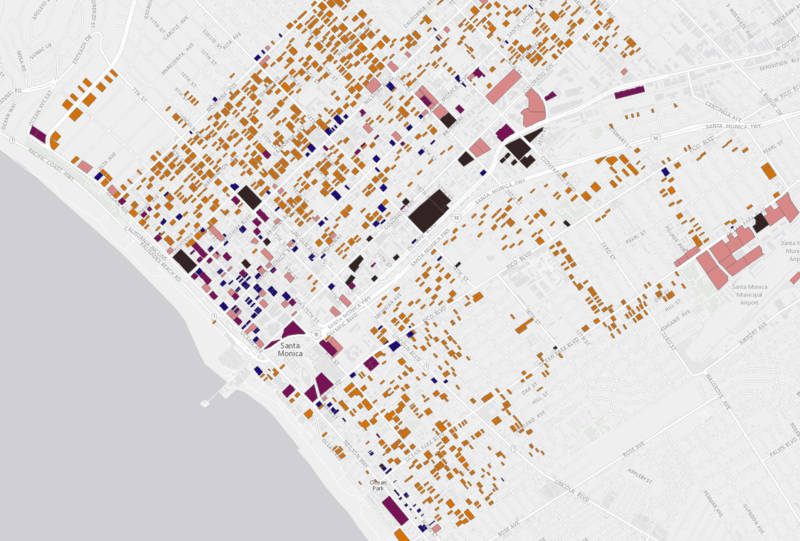

The California Geological Survey’s newly released mapping of the Santa Monica Fault could, if approved after a 90-day public comment period, prohibit new construction on top of active sections of the fault and require extensive geological review for proposed development within 500 feet.

“The Santa Monica and Hollywood faults historically have been fairly quiet since the area’s been settled, as far as we know,” says California Geological Survey senior engineer Timothy Dawson. “The major concern is that these faults cover some of the most densely populated areas in the L.A. basin.”

The Santa Monica Fault helped shape a roughly 30-mile stretch from Pasadena to the Pacific. It’s why properties along sections of Santa Monica Boulevard in West L.A. — like the immense temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — sit a little higher than those on the other side.

“What the fault has done mostly is create these things called fault scarps. The Mormon temple is actually on top of one of these fault scarps related to the Santa Monica Fault,” says Dawson. “Some geologists have referred to (it) as the most beautifully manicured fault scarp in the world.”