Robert Bowers, the man accused of killing 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue on Saturday, posted about his hatred of Jews on the social network Gab for months beforehand.

Gab was founded two years ago by a San Mateo-based Trump supporter named Andrew Torba. It’s a lot like Twitter, but without what Torba would call “censorship” of ideas unpopular with people on the political left.

The platform is now offline and looking for a new hosting provider. But whatever happens to the site, there’s a market for platforms like Gab, a haven for alt-right enthusiasts. That troubles Brian Levin, who directs the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.

“What are the costs of segregating bigots into their own ecosystem, creating virtual universities for hate that aren’t on the more well-known mainstream social media platforms?” Levin said.

Gab reportedly has nearly 700,000 users — that’s tiny compared to the billions that Facebook, YouTube and others collectively boast. But hate speech watchers say many people with extreme views want to be on “mainstream” platforms because of the huge audiences they serve.

Scrubbing Away Hate

Silicon Valley is spending millions to scrub hate speech from social media, but it’s a complicated and controversial task.

From Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg on down, tech leaders all boast of the promise of artificial intelligence and machine learning. But hate speech posters prove time and again they can easily game even the most sophisticated AI.

Keyword flagging algorithms often miss simple hacks, like inserting a “$” for an “S.” Sure enough, tech giants have hired tens of thousands of human screeners to help flag hate speech, because humans are still much better at picking up on the subtleties of cultural context. They can decipher the dollar sign strategy, and much more insidious, buried code language.

Take “Shrinky Dinks,” a toy that became popular in the 1980s. You cut figures out of polystyrene sheets and bake them in an oven where they shrink to form little charms.

Some people online use “Shrinky Dinks” today to refer to Jews, because the Nazis shoved Jews into ovens during the Holocaust.

“This is something that probably wouldn’t be caught by a machine learning-based algorithm because it’s the name of a 1980s toy, and not commonly associated with hate speech, unless you know the target,” explains Brittan Heller, director of technology and society at the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a group established to fight anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry.

Heller is ADL’s point person for Silicon Valley and consults with Microsoft, Twitter, Facebook and Google about defining and combating hate speech. But humans drive AI, and Heller says the industry is going to have to address its systemic weaknesses in human hiring. “Tech companies aren’t very diverse, and hate speech is dependent on context and in-group knowledge,” according to Heller.

That said, Heller is generally positive about the possibilities of AI. “Hate speech is a fluid animal, and is constantly shifting. Machine learning and AI identify patterns over a large data set. So as long as you keep having input to your AI, you can identify these changes in meaning and context.”

Facebook and Twitter, asked about the diversity of their hate speech screening workforce, both declined to provide detailed statistics. Facebook spokeswoman Carolyn Glanville wrote, “In some countries, it is illegal to ask these questions as part of the hiring process. We aren’t able to keep diversity statistics on all. But … language and cultural context is the most important thing we hire for, as well as a diverse background to reflect that of the community we serve.”

![An illustration from a blog called "Voices From Russia." In the accompanying blog post, the author writes, "When you support [the Jewish Hungarian-American investor and political activist] George Soros, you support shrinky-dinks and judges taking kids away from their families."](https://ww2.kqed.org/news/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/10/Shrinkydink202.jpg)

A More Transparent Approach to Defining Hate Speech

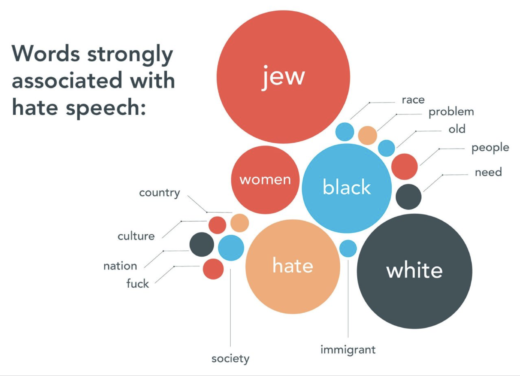

Heller is also working with UC Berkeley’s D-Lab, which partners with academics and organizations on data-intensive research projects. They’ve created The Online Hate Index to collect incidents of hate speech and to define what constitutes hateful speech.

D-Lab Executive Director Claudia von Vacano says the index uses Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service to develop a rubric for defining hate speech that isn’t hidden behind the proprietary walls that companies like Facebook or YouTube put up. “What we’re developing is an ability to speak across different platforms in a very public and transparent way, so that the public can investigate, and be invested, and help us in the understanding of hate speech as a linguistic phenomena,” von Vacano said.

All too often, social media companies have their own internal agendas determining what constitutes hate speech and whether a particular instance merits banning or deletion.

Heller said, the index “approaches hate speech from the target’s perspective, and it creates community-centric definitions of what hate speech is. We don’t want tech companies to tell us what is or is not hate speech.”

Watch Reddit Vice President and General Counsel Melissa Tidwell, approximately 12 minutes and 30 seconds in, discuss some of the challenges of moderating hate speech.

A Fool’s Errand?

There are those who argue scrubbing social media of hate speech is a fool’s errand, even if social media networks have the legal right to enforce their terms of service.

New York Law School professor Nadine Strossen, immediate past president of the ACLU, wrote a book called “Hate: Why We Should Resist it With Free Speech, Not Censorship.” Screening for hate speech, she argues, is an “inherently subjective undertaking, no matter who is engaging in it: a government official, a campus official, a business executive or artificial intelligence.”

Strossen added, “Having diverse enforcers is not going to be a solution.” She says enforcement tends to come down more frequently against minority viewpoints, an issue that’s particularly problematic in non-democratic countries.

Strossen prefers to see hate speech posters out in the proverbial sunlight, as opposed to tucked away on platforms like Gab.

“I think it’s really important to know about them, and we’re going to be more effective in identifying and refuting those ideas, and in monitoring the people who have them and preventing them from engaging in hateful actions if we know who they are,” Strossen said.

But how, exactly, do you identify somebody about to switch from hateful words to hateful actions? That’s not something artificial — or human — intelligence has been able to decipher yet.