About three years ago, Du Bois called the school superintendent of the Sequoia Union High School District in San Mateo County to find out why she was receiving a daily email of her son’s grades. The superintendent at the time told her the portal was working as it should.

"I went crazy," said Du Bois. "I couldn’t believe that was our intent."

Du Bois called every mental health professional she knew and they all told her the same thing: The supply of constant data on academic progress can overemphasize the importance of grades. Her district has since changed systems and no longer sends out daily grade updates.

However, hundreds of other schools in the Bay Area still do. Steven Adelsheim, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, said it takes away student's freedom to make mistakes, to work through and solve problems.

"We talk about innovation in this area a lot. But you know the notion of innovation also includes being able to feel comfortable trying things and risking and failing," said Adelsheim. "When our focus is always on being successful and getting the A, we're not allowing necessarily the room for creativity in the room to attempt things."

Adelsheim said that while there are no scientific studies out there about the mental health impacts, he has had troubling conversations with students about daily grades.

"There’s already a great deal of pressure that they’re feeling on their own and from their friends, and this potentially adds to it. It creates both stress and anxiety," Adelsheim said.

A spokeswoman for the Santa Clara Unified School District, the one my family is part of, said the feedback they’ve received from parents is overwhelmingly positive. The district uses the portal School Loop, which is also used by more than 3,500 schools in 30 states. Other parents have also told me the portals give them insights into their kids' lives and open up conversations beyond “how was your day.”

But other critics say the portals have become a thorn in the sides of educators. Former high school English teacher Amanda Parrish Morgan wrote an op-ed piece in The Washington Post about how disturbed she was, watching students in the hallways between classes frantically checking their phones to see their latest grades.

"We could stand in front of a classroom and do a mental health initiative where we're trying to talk about ... being a whole person is more important than your accomplishments," said Parrish Morgan. "But I feel like it really sends the message to kids that this number is what matters."

Most of the portals offer parents the option of turning off daily notifications.

Mental health care professionals advise that a healthier and more accurate measure of progress is checking grades once a week or even once a month.

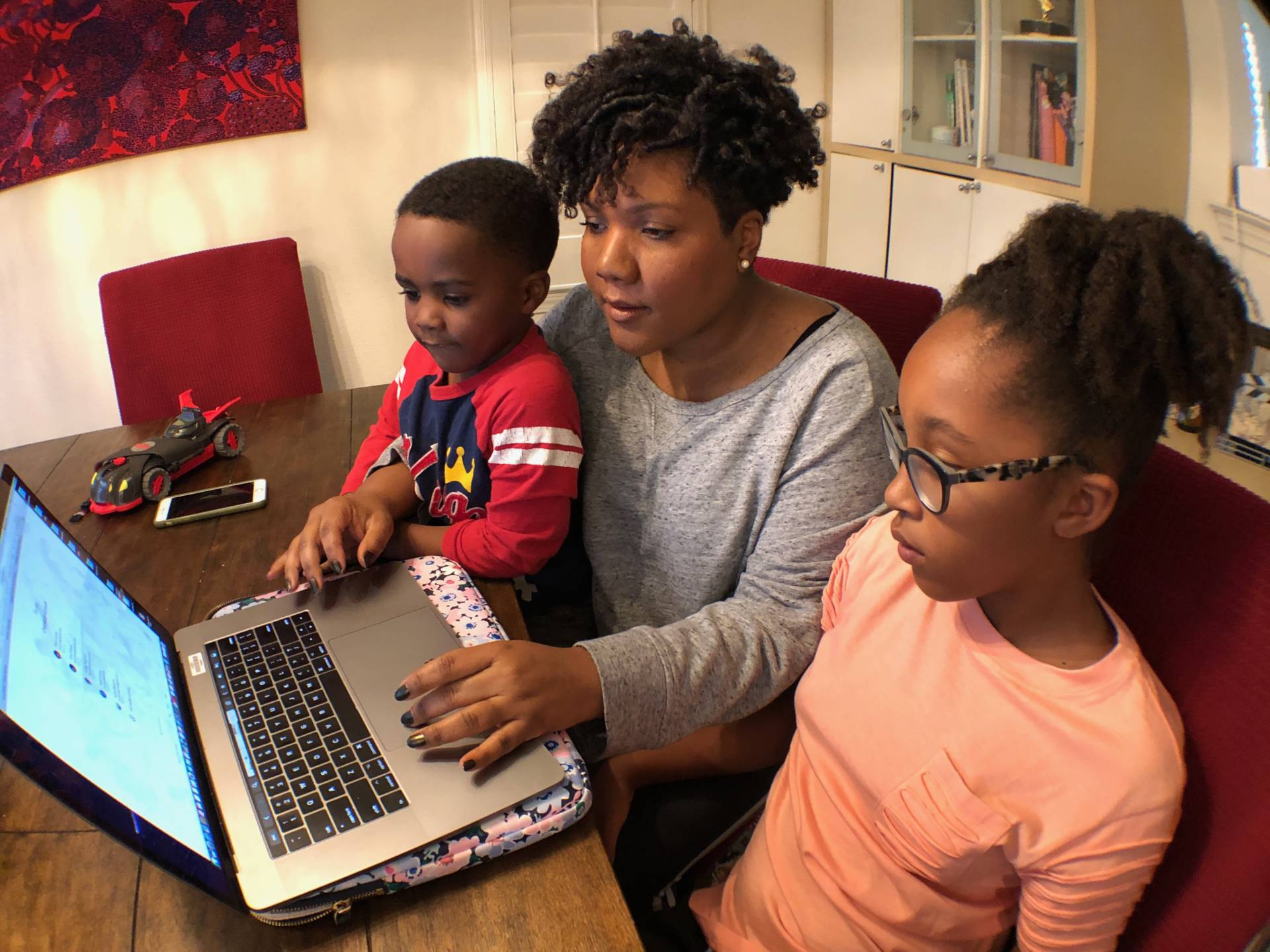

It’s what I have decided to do, so that Audrey and I can spend our time talking about the important things, her experiences in life, what she’s learning, and the stuff that makes being 11 cool.