This was originally published Feb. 8, 2019.

She and her roommate had been awake for two days straight. They decided to spray-paint the bathroom hot pink. After that, they laid into building and rebuilding the pens for the nine pit bull puppies they were raising in their two-bedroom apartment.

Then the itching started. It felt like pin pricks under the skin of her hands. Amelia was convinced she had scabies, skin lice. She spent hours in front of the mirror checking her skin, picking at her face. She even got a health team to come test the apartment. All they found were a few dust mites.

“At first, with meth, I remember thinking, ‘What’s the big deal?’ ” Amelia says. “But when you look at how crazy things got, everything was so out of control. Clearly, it is a big deal.”

While public health officials have focused on the opioid epidemic in recent years, tallying heroin deaths and cracking down on pill prescriptions, another epidemic has been brewing quietly, but vigorously, behind the scenes.

Methamphetamine is back. In San Francisco, over the last five years, Drug Enforcement Administration seizures of meth have jumped, hospitalizations and emergency room visits have spiked and deaths have doubled. The toll the drug is taking on the city’s public health, emergency response and police departments is now spurring the mayor to establish a task force to combat the new speed epidemic.

"It's something we really have to interrupt," says San Francisco District 8 Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, who will co-chair the meth task force with Mayor London Breed. "Over time, this does lasting damage to people's brains. If they do not have an underlying medical condition at the start, by the end, they will."

Since 2011, emergency room visits related to meth have jumped 600 percent to 1,965 visits. Admissions to the hospital are up 400 percent to 193. At Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, of 7,000 annual psychiatric emergency visits, 47 percent are people who are not necessarily mentally ill — they’re high on meth.

“They’re often paranoid, they’re thinking someone might be trying to harm them. Their perceptions are all off,” says Dr. Anton Nigusse Bland, medical director of psychiatric emergency services, describing the signs of methamphetamine-induced psychosis.

For example, someone starts walking into traffic on Sixth Street, shouting, taking off his shirt. A bystander calls 911 and reports a mentally disturbed person, then the police come and deliver him to Nigusse Bland’s department at San Francisco General.

“They can look so similar to someone that’s experiencing chronic schizophrenia,” he says. “It’s almost indistinguishable in that moment.”

If the person is really agitated, doctors might give them a benzodiazepine to calm down, or even an anti-psychotic. Otherwise, the treatment is just waiting 12 to 16 hours for the meth to wear off. No more psychosis.

“Their thoughts are more organized, they’re able to maintain adequate clothing. They’re eating, they’re communicating,” Nigusse Bland says. “The improvement in the person is rather dramatic because it happens so quickly.”

'Meth causes people to act completely insane'

For some people recovering from addiction, the memories of meth-induced psychosis are part of what motivates them to stay sober.

For Amelia, the scabies scare is what alerted her mother to her addiction, forcing an intervention. Even though she did not have scabies, the itchy feeling and the fear are vivid, even a year and a half later.

“I still don’t really want to say it out loud that it wasn’t real,” says Amelia, now 33, who asked that we not reveal her last name to protect her family’s privacy.

For Kim, another woman in recovery, there was one day last year when she says she went wine tasting with a friend in Sonoma. She was high on Xanax and speed.

“I was crazy,” says Kim, 47, who also asked that we not reveal her last name. “Meth causes people to act completely insane.”

She and her friend got in an argument in the car. Kim thought someone was behind them, following them. She was utterly convinced. And she had to get away.

“I jumped out of the car and started running, and I literally ran a mile. I went through water, went up a tree, and I was literally running for my life,” she says. “I literally thought I was being chased.”

Kim was soaking wet when she walked into a woman’s house, woke her from bed and asked for help. When the woman went to call the police, Kim left and found another woman’s empty guest house to sleep in — Goldilocks-style. Kim says she just wanted to get warm.

“But then I woke up and stole her car,” she says.

That’s how Kim ended up in jail. She’s in a residential treatment program in San Francisco now, part of the steady rise in people seeking help for meth addiction. Rehab admissions for meth are up 25 percent since 2015.

The trend in rising stimulant use is nationwide: cocaine on the East Coast, meth on the West Coast, says Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a professor and substance use researcher at UCSF.

“It is an epidemic wave that’s coming, that’s already here,” he says. “But it hasn’t fully reached our public consciousness.”

Drug preferences are generational, Ciccarone says. They change with the hairstyles and clothing choices. It was heroin in the 1970s, cocaine and crack in the '80s. Then opiate pills. Then methamphetamine. Then heroin. And now meth again.

“The culture creates this notion of let’s go up, let’s not go down,” Ciccarone says. “New people coming into drug use are saying, ‘Whoa, I don’t really want to do that, I hear it’s deadly, people look really doped up and they’re not that fun to be with, I’m going in a different direction.’ ”

Kim has been with meth through two waves. When she got into speed in the 1990s, she was hanging out with a lot of bikers, going to clubs in San Francisco.

“Now what I see, in any neighborhood, you can find it. It’s not the same as it used to be where it was kind of taboo,” Kim says. “It’s more socially accepted now.”

Meth-related deaths

A hint about who is using meth today comes from the data on deaths. Since 2011, meth-related deaths in San Francisco have doubled.

One hypothesis that experts have come up with to explain this is that meth users are aging. Most meth deaths are from brain hemorrhage or a heart attack — that would be highly unusual for a 20-year-old.

“Because your tissue is so healthy at that age,” says Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of substance use research at the San Francisco Department of Public Health. “Whereas when you’re 55 years old and using methamphetamine, you might be at higher risk for bursting a vessel and bleeding and dying from that.”

Older adults have higher blood pressure, maybe heart disease, that makes their heart weaker.

“So stimulant-related death, really, you shouldn’t see it affect so many young people,” Coffin says.

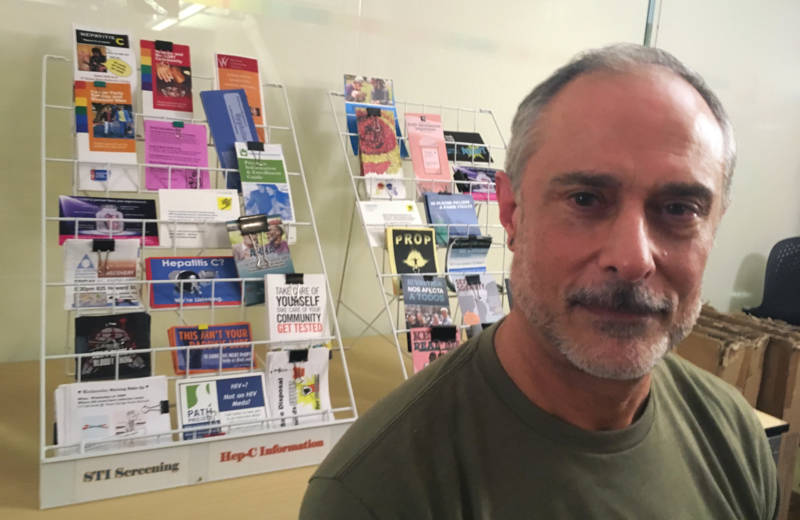

At the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, which runs a 12-week program to help men who have sex with men stop using meth called Positive Reinforcement Opportunity Project (PROP), program manager Rick Andrews has noticed a trend in older men coming in for help.

“Older gentlemen who grew up in the time of HIV and AIDS initially, maybe they led very safe lifestyles, and now they’re older,” he says.

Now that things are different with HIV — there’s treatment, there’s a prevention pill, PrEP — they’re taking a new approach to the often drug-fueled party scene.

“They feel like they’ve missed out and they want to have a little fun and make up for lost time maybe,” Andrews says.

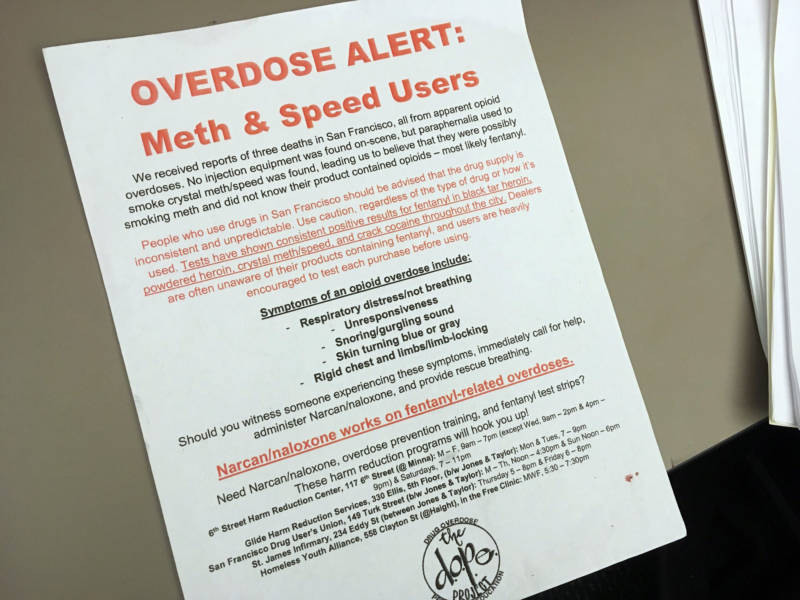

There are some young people who have died from using meth. Last year, three young people in San Francisco died after smoking meth together — it turns out the meth had fentanyl in it. The synthetic opioid has been causing waves of heroin overdoses across the country, but now it’s showing up in cocaine and meth.

“A lot of my patients who primarily use meth will say, ‘I used to have a lot of energy when I used meth, but now I feel like I need to go to bed,’ ” says Dr. Ako Jacintho, who runs addiction services at a HealthRIGHT 360 community clinic in San Francisco. Their tests indicate some meth from the streets is tainted with fentanyl.

Last year, it was believed about 10 to 15 percent of meth in San Francisco had fentanyl in it, says Coffin of the San Francisco Public Health Department, but that has dwindled and is now more rare. He and other researchers believe the contamination is accidental.

“The whole idea of the evil drug pusher who’s trying to create a market by getting their cocaine users hooked on fentanyl. I would highly doubt that,” says UCSF’s Ciccarone.

Dealers know that people are particular about their drugs, he says. It doesn’t make sense to alienate a customer base like that.

“Take coffee drinkers, for example. I’m a Peet's drinker, my partner is a Starbucks drinker. You know what style of coffee bean you like,” Ciccarone explains. “Well, folks that are doing hardcore illicit drugs can be pretty fussy, too. And most meth users really, really, really, really don’t want an unbeknownst fentanyl put into their methamphetamine.”

More likely, Ciccarone says, the same table that was used to cut and bag fentanyl later got used to bag meth.

Deliberate or not, health officials call this poisoning. They started distributing fentanyl test strips to meth users so they can test their drugs. But counselors like Rick Andrews say the strips aren’t refined – even trace amounts will give a positive result.

“I hear guys saying, ‘Oh, there’s test strips and I’m testing. It’s positive, but I do it anyway and everything’s fine,' ” Andrews says.

That’s why they’re also giving out Narcan, the nasal spray that can reverse an opioid overdose, Andrews says. They’re telling meth users to carry it just in case.

Are opioids driving meth use?

Some experts believe the new meth crisis got a kick-start from the opioid epidemic.

“There is absolutely an association,” Coffin says.

Amelia’s introduction to meth is a case in point.

At first, drugs were just a fun thing she would do on the weekend — ecstasy and cocaine with her friends, then on Monday Amelia went about her workweek.

“I’m a horse trainer, so I worked really hard, but I also partied really hard,” she says.

Then one weekend, when they were feeling kind of hungover from the night before, Amelia’s friend passed her a pipe. She said it was opium.

“I thought it was like smoking weed or hash, you know? I just thought it was like that,” Amelia says.

She grew to like this opium stuff. She took her friend’s phone to get her dealer’s number, then met up with her.

“The woman said, ‘How long have you been doing heroin for?’ and my jaw nearly hit the ground. I was just really, honestly, shocked. I was like, ‘What? I’ve been doing heroin this whole time?’ I felt really naive, really stupid for not even putting the two together."

Pretty soon, Amelia started feeling sick around the same time every day. Her weekend smoke became her daily morning smoke. Then it was part of her lunch break routine.

“I just kind of surrendered to that and decided, ‘Screw it,’ ” she says. “I’ll just keep doing it. I’m obviously still working, I’m fine.”

Heroin is expensive. She was working six days a week to pay for it. Any horses that needed to be ridden, any lessons that needed to be taught, she said yes, because she wanted the money.

But it was exhausting. One day, one of the girls she worked with at the barn offered her some meth, as a pick-me-up.

Meth was cheap. Soon, it was the thing that kept Amelia going so she could earn enough money to buy heroin.

“The heroin was the most expensive part,” she says. “That was $200 a day at one point. And the meth was $150 a week.”

This lasted for three years. Then Amelia found out she was pregnant, when she was already 6½ months along. Finally, she was motivated to get sober. She got into a residential treatment program at the Epiphany Center for women struggling with addiction.

“I was OK with being a drug addict. I was OK with that being my life,” she says. “But now that she’s here – I wasn’t OK with having kids and letting that be part of my life.”

Rehab admissions up for people who use heroin and meth

Admissions to drug rehab for heroin have remained steady in recent years in San Francisco. But the number of heroin addicts reporting methamphetamine as a secondary substance problem has been rising. In 2014, 14 percent of heroin users said meth was also a problem. Three years later, 22 percent said meth was also a problem.

“That is high, that is very high,” says UCSF's Ciccarone, who has been studying heroin for almost 20 years. “That’s alarming and new and intriguing and needs to be explored.”

Doctors and users in San Francisco say it’s mainly a back-and-forth with heroin and meth, the way a lot of people have coffee in the morning to wake up and a glass of wine in the evening to wind down. Meth on Monday to get to work, heroin on Friday to ease into the weekend.

For Kim, methamphetamine came first. She was in treatment for meth when she went out to help a friend who was on the brink of relapse. The friend offered Kim heroin. She tried it, then later freaked out that she had used a needle, something she swore she would never do. She told her counselor, but the treatment program had a strict abstinence policy, and she got kicked out.

“That put me on a nine-year run of using heroin,” Kim says. “I thought, ‘Oh, heroin’s great. I don’t do speed anymore.’ To me, it saved me from the tweaker-ness.

“And then I ended up doing both, at the same time, every day, both of them,” she says.

For Kim, it was all about finding the recipe to what felt normal. Start with meth. Add some heroin. Touch up the speed.

“You’re like a chemist with your own body,” she says. “You’re balancing, trying to figure out your own prescription to how to make you feel good.”

Now Kim is trying to find that balance without drugs. She’s been through rehab multiple times but, she says, getting tangled up with the legal system is what made her want to change her life. She’s been clean for eight months.

Amelia has been sober for a year – her anniversary is the same as her daughter’s birthday.