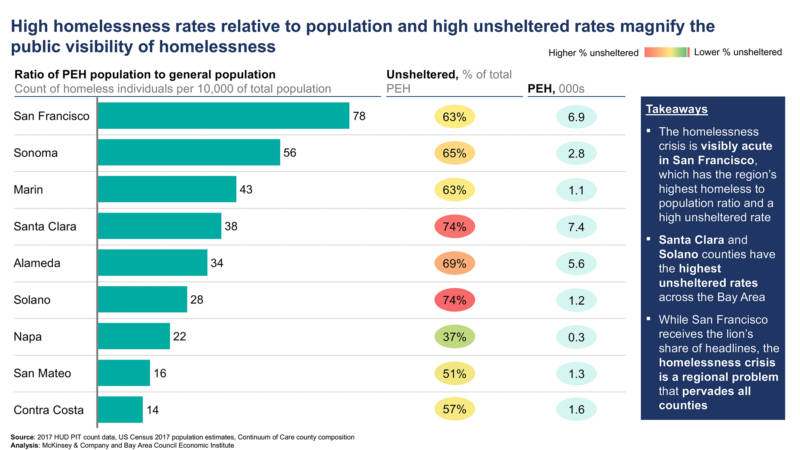

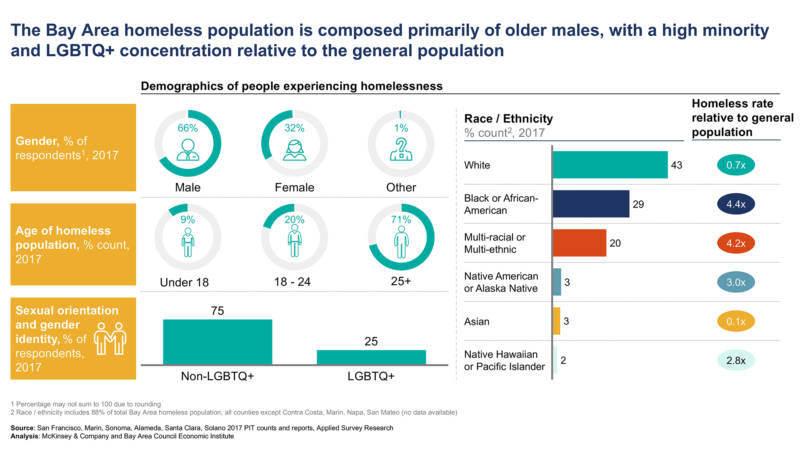

The Bay Area has the third-largest homeless population in the United States, with nearly 70% living unsheltered — on the streets, in cars, tents or elsewhere, according to a new study about homelessness in the region.

Bay Area Has 3rd-Largest Homeless Population in Country; Nearly 70% Have No Shelter

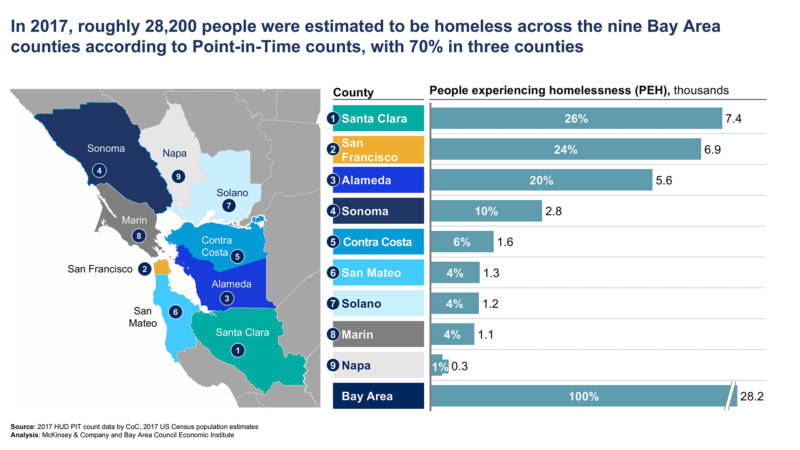

Some 28,200 people are homeless in the Bay Area, behind New York City with 76,500 and Los Angeles at 55,200, according to the study published Wednesday. It was commissioned by the business lobbying group the Bay Area Council with research and data provided by McKinsey & Co.

The region has tried stemming homelessness through new approaches. Oakland and San Jose have built communities of tiny homes and portable shelters, while San Francisco has focused on providing social services and support in addition to providing shelter.

Through its navigation centers and other programs, San Francisco offers assistance with finding housing, moving and paying rent, and case management, making it the top provider of so-called supportive housing per resident in the country, the study found.

And yet, a larger number of people in the Bay Area are experiencing homelessness for the first time.

“The population of homeless people in the region has been growing at a time of expanded economic opportunity. That shouldn’t be the case,” said Adrian Covert, vice president of public policy at the Bay Area Council. “The problem is bigger than we even thought it was before.”

A Regional Problem

The homeless in the Bay Area tend to stay in the region, but move around between cities and counties. As they transit, it becomes more difficult and expensive for care providers to reconnect with them and evaluate what types of services have worked and failed.

“We need to change the way fundamentally that we think about homelessness. It’s not a problem of any one particular city. It’s not a problem facing any particular county,” Covert said. “It’s a regional problem facing the Bay Area and we need to start thinking about it that way.”

One of the reasons the homeless move around so much: Not enough shelter. New York, Covert said, has a homeless population more than double that of the Bay Area yet can provide shelter to 95% of them. In the Bay Area, 67% of homeless are unsheltered.

“We shouldn’t be surprised that they move around to try to find the safest place that they can to rest,” he said. “We need as a region to have a tough conversation about what types of shelter accommodations that we need to build and in what numbers and where.”

The lack of shelter points to a larger housing issue facing the Bay Area: a lack of affordable or government-subsidized homes. For those households earning less than 30% of the area median income (known as extremely low-income or ELI), the region’s expensive housing market severely “narrows the margin between housing insecurity and homelessness,” according to the study.

In the Bay Area, some 306,000 households qualify as ELI, and two-thirds of them, about 196,000 spend more than 50% of their income on rent, often leaving less than $1,000 a month for other basic expenses. While Alameda County has the highest number of such rent-burdened households, Solano, Sonoma and San Mateo counties have the highest proportion of them.

“We haven’t been able to build homes at the pace that we need to, which has driven more people on the street,” Covert said, calling it a “farm system to homelessness.”

Even if the region could sustain 2017’s rate of a 2,500 annual increase in permanent support housing units, at the current growth rate of homelessness, the Bay Area wouldn’t be able to provide beds for all homeless residents until 2037, the study said.

Some of the study’s recommendations include creating a new state tax credit program for building homes for extremely low-income households, dramatically expanding the supply of permanent supportive housing, emergency and longer-term shelters, and consolidating existing state programs into a new California Homeless Services Agency.