More than 700 measles cases have been confirmed in 22 states so far this year, with 78 of those cases reported in the previous week, according to Monday’s update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s the highest number reported in the U.S. since 1994.

The Feverish Roots of Today's Anti-Vaccine Movement

Of those cases, more than 500 have been found in people who had not been vaccinated, the federal agency said, including about 400 in mostly Orthodox Jewish communities in the New York region. And late last week, a quarantine order was issued for hundreds of students and staff at two Los Angeles universities who may have been exposed to measles and don’t have vaccination records.

With this latest outbreak comes plenty of angry finger-pointing at the small but notorious contingent of Americans who choose not to vaccinate their children (or themselves) against the highly contagious, yet preventable, disease.

As recently as three decades ago, measles was listed by the World Health Organization as one of the five leading causes of death on Earth. But by 2000, the disease was declared “eliminated” in the U.S., largely due to the success of statewide public health campaigns to make the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine mandatory for children enrolling in public schools.

Since then, however, the number of parents requesting religious or philosophical exemptions to state rules has gone up, as have reported measles cases. In 2014, the CDC reported what was then the highest number of cases in over a decade: 644 in 27 states, including one outbreak in an Amish community in rural Ohio infecting more than 300 people.

Forty-seven states still permit parents to opt out of vaccinating their children on religious grounds, and 18 states allow exemptions based on personal or philosophical beliefs (until 2015, California allowed both exemptions). Many parents who go this route say they doubt the effectiveness of the vaccine or have concerns that it may cause autism or other major health problems, even though no medical evidence actually supports these theories.

These holdouts mark just the latest chapter in a long, robust history of anti-vaccination movements. Intermittent backlashes against compulsory government vaccination campaigns have arisen ever since the first series of vaccinations were given more than 200 years ago.

Most interesting are the striking cultural similarities and motives of today’s prototypical “anti-vaxers” and their 19th century forebears: Both have typically been cast as either deeply religious or affluent, well-educated and politically progressive, and intensely protective of civil liberties and personal choice.

The First Vaccine Revolution

If you know little or care less about smallpox, Edward Jenner’s the guy to thank for that.

Among the most gruesome and deadly diseases in human history, smallpox terrorized the world for centuries, ravaging entire civilizations and claiming millions of lives — particularly those of young children — during its sporadic outbreaks. Highly infectious, the disease typically covers the skin in large oozing, pus-filled bumps.

In 1796, Jenner, a rural British physician, tested a locally shared theory that milkmaids who contracted cowpox were immune from smallpox. Similar to smallpox but far less severe, cowpox is generally found in animals and can be transmitted to human handlers. Jenner extracted pus from a cowpox scab and inserted it into an incision on the arm of an 8-year-old boy. Although the child contracted a mild virus, he recovered quickly, developing antibodies that built up his immunity to both cowpox and smallpox.

Jenner subsequently coined the term “vaccine,” from “vacca,” Latin for cow.

Although initially rejected by the British medical establishment, Jenner’s findings were eventually published after subsequent successful trials, and the field of modern immunology was born. The discovery paved the way for vaccine breakthroughs over the following two centuries, including inoculations for polio, tetanus, influenza, rabies, diphtheria and, yes, measles.

The smallpox vaccine and its later iterations proved so successful that the World Health Organization in 1980 declared it the first disease to be eradicated as a result of global vaccination efforts. To date, there is no cure or treatment for it; vaccination is the only means of prevention.

Birth of the Backlash

Protection from one of the most feared, miserable ailments in human history: Who wouldn’t raise a (sterilized) glass to that?

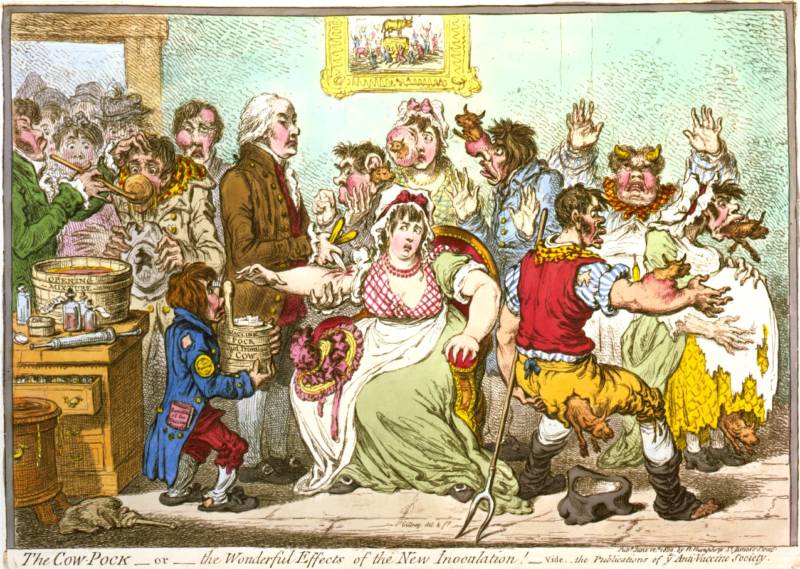

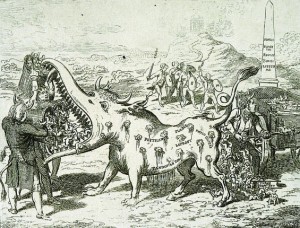

Turns out, lots of folks. As word of the procedure spread, Jenner was ridiculed by a host of angry critics, particularly members of the clergy, who charged that the idea of inoculating someone with pus from a diseased animal was not only revolting but blasphemous. Rumors abounded of vaccinated patients contracting bovine diseases and suffering grotesque reactions. Enough evidence, however, demonstrated the obvious advantages of the vaccination, and the procedure became increasingly accepted by the medical establishment in much of Europe.

By the mid-1800s, in the wake of several smallpox outbreaks, the United Kingdom enacted a set of laws making vaccinations compulsory, initially for infants, but eventually for all children up to 14 years old. Cumulative penalties were imposed on violators.

These measures, though, were met with staunch resistance, inciting a series of riots. The unrest prompted the creation of the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League in 1867, whose founders were primarily concerned with what they considered a blatant infringement of personal choice and liberty.

The group’s seven-point mission statement, printed on the masthead of its newsletter, included the following pronouncement:

“As parliament, instead of guarding the liberty of the subject, has invaded this liberty by rendering good health a crime, punishable by fine or imprisonment, inflicted on dutiful parents, parliament is deserving of public condemnation.”

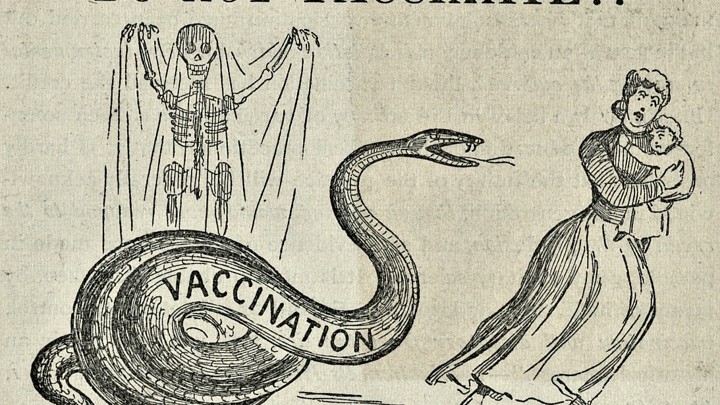

By the 1870s and ’80s, even as smallpox vaccination techniques were rapidly advancing and helping to contain the disease’s spread, anti-vaccination campaigns continued to gain momentum in the U.K. and elsewhere. Propaganda literature proliferated as leaders of the movement adeptly tapped into the public’s understandable anxieties about the still nascent procedure. Some efforts were successful in temporarily lowering vaccination rates.

One of the largest demonstrations, in Leicester, England, in 1885, drew upward of 100,000 people, with a child’s coffin and an effigy of Jenner among the props exhibited.

The rally prompted a government commission to investigate the protesters’ grievances, which eventually concluded that the vaccine was safe and effective. But in a political move to pacify detractors, the report also recommended the abolition of penalties for violators. In 1898, the passage of a new national vaccination act removed such penalties and included a “conscientious objector” clause, allowing parents concerned with the safety of vaccinations to apply for an exemption certificate.

The anti-vax fever spreads to America

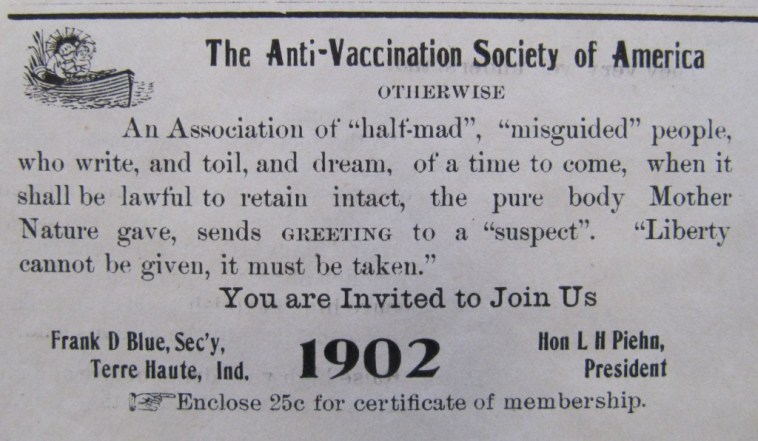

In the late 1800s, a series of smallpox outbreaks in the United States spurred a number of local government vaccine campaigns. That, in turn, prompted fierce opposition, including a visit from William Tebb, a prominent British anti-vaccine activist. By 1879, the Anti-Vaccination Society of America was established, followed by the emergence of several local leagues, including the New England Anti Compulsory Vaccination League and the Anti-Vaccination League of New York City. A second national league was formed in the early 1900s. Activists waged court battles to repeal vaccination laws in a number of states, including California, Illinois and Wisconsin.

In a response that inflamed tensions and helped further cast vaccination campaigns as an affront to civil liberties, public health officials commonly resorted to heavy-handed, inconsistent enforcement tactics, often vaccinating immigrants and minorities against their will during outbreaks, writes University of Georgia history professor Stephen Mihm.

Fears were also legitimately stoked by the lack of oversight in the production of vaccines, a process primarily controlled by private industry that was loosely regulated and at times resulted in questionable, unsafe products. In one of the worst incidents, nine children in Camden, New Jersey, died after being inoculated with a batch of smallpox vaccine that had been contaminated with tetanus. News of the tragedy prompted Congress to pass the Biologics Control Act of 1902, increasing government oversight of the manufacturing process.s

Following a smallpox outbreak in 1902, the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, mandated vaccinations for all residents. After one man refused to comply on the grounds that the law violated his right to care for himself, the city filed criminal charges against him. The case — Jacobson v. Massachusetts — eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately sided with the state, ruling that it was within its power to enact mandatory vaccine laws in order to protect the public in the event of a communicable disease. The decision marked the first Supreme Court case determining the extent of state power in enacting public health law.

Modern times

Anti-vaccination fervor erupted again in England and spread abroad in the latter half of the 20th century, this time after an errant 1970s medical study alleged that the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) vaccine had caused neurological disorders in children. The report fueled a wave of public outcry and subsequent false analyses, leading to decreased vaccination rates and three major outbreaks of pertussis (whooping cough), despite an independent advisory committee confirming the safety of the immunization.

The controversy over DTP reached the United States after a 1982 documentary, “DPT: Vaccination Roulette,” and a 1991 book, “A Shot in the Dark,” alleged adverse reactions to the vaccine and questioned its effectiveness. Amid the ensuing media storm, scores of parents formed advocacy groups opposing the immunization and, in several cases, sued vaccine manufacturers. Hoping to not repeat England’s example, U.S. medical organizations, like the Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, aggressively countered the false claims, and more effectively stemmed the decrease in vaccination rates.

And then came the anti anti-measles movement.

Despite the MMR vaccine’s safe and effective application since it was introduced in the 1960s, fear over the inoculation spread like wildfire after a 1998 medical study, and a subsequent flurry of media coverage, suggested a connection between the vaccine and the onset of autism. The study was later discredited, and an independent medical board determined that its author, British doctor Andrew Wakefield, had a “fatal conflict of interest” after revelations that he had been paid by lawyers representing parents who believed the vaccine had harmed their children.

More than a decade later, after numerous subsequent studies that found no evidence of any link between the vaccine and autism, the paper was formally retracted by The Lancet, the journal that first published it, and labeled “utterly false.” Wakefield was also stripped of his medical license.

But the seed had been planted, and parents already skeptical about immunizing their children were further motivated to avoid the vaccine at all costs.

Since then, fears have been further inflamed by a number of anti-vaccination campaigns suggesting the linkage to an increased incidence of autism. Perhaps most well-known is the ongoing activism of actress and model Jenny McCarthy, who became the veritable poster child of the anti-vax movement when she began publicly questioning the safety of vaccines after her 2-year-old son was diagnosed with autism.