Sexual assault in jail. Domestic violence complaints against an officer ignored. Knocked-out teeth followed by a cover-up.

Throw in tens of thousands of stolen bullets, an illegal chokehold, falsified police reports and cavorting with sex workers, and you've got an emerging picture of what California's new police transparency law has revealed in its first six months.

Those cases involving California peace officers are some of the incidents recently made public due to a landmark transparency law that undid decades of secrecy surrounding police internal affairs files.

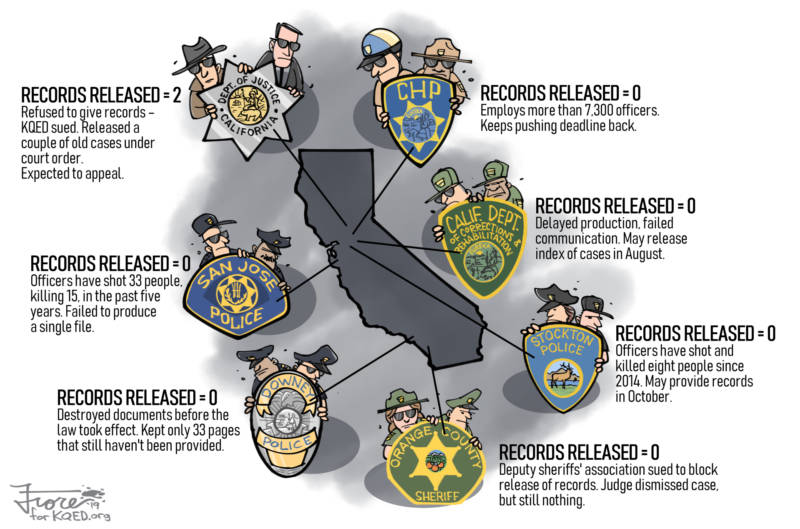

But six months after Senate Bill 1421 went into effect, some of the state’s largest law enforcement agencies haven’t provided a single record.

Some law enforcement organizations are charging high fees for records, destroying documents and even ignoring court orders to produce the files.

'Dragging Their Feet'

The law, authored by state Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Berkeley, covers records of shootings by officers, severe uses of force and confirmed cases of sexual assault and dishonesty by officers. Skinner said the revelations that have come out so far are proof that the law is working to shed sunlight on police misconduct.

But she said it’s troubling that major state agencies, such as the California Highway Patrol, which employs more than 7,300 officers, haven’t yet produced a single record.

“If the state agencies themselves are acting like they're above the law, that's absolutely the wrong model and the wrong example to set for the rest of the local government agencies up and down the state,” Skinner said.

Skinner said she plans to call for oversight hearings to push for full disclosure.

“We'll have to start being more proactive about really poking them if they're dragging their feet,” she said.

Officials with many law enforcement agencies insist they’ve done nothing wrong, saying they are trying to release records as best they can. They also dispute that there is anything improper about the records that have been destroyed.

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva acknowledged earlier this year that public records requests were "stacking up." He has said he’s asked the county Board of Supervisors for funding to hire more people to handle requests.