Immigration enforcement has been one of President Trump’s central issues. Immediately after taking office three years ago, his administration announced a series of policies designed to limit both legal and illegal immigration, and restrict access to asylum in the United States. Among the most controversial is the practice of migrant family separation, in which border agents have forcibly taken thousands of children away from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border, ostensibly to facilitate the prosecution of adults for crossing the border without authorization.

Zero Tolerance: An Ongoing History of Family Separations at the US-Mexico Border

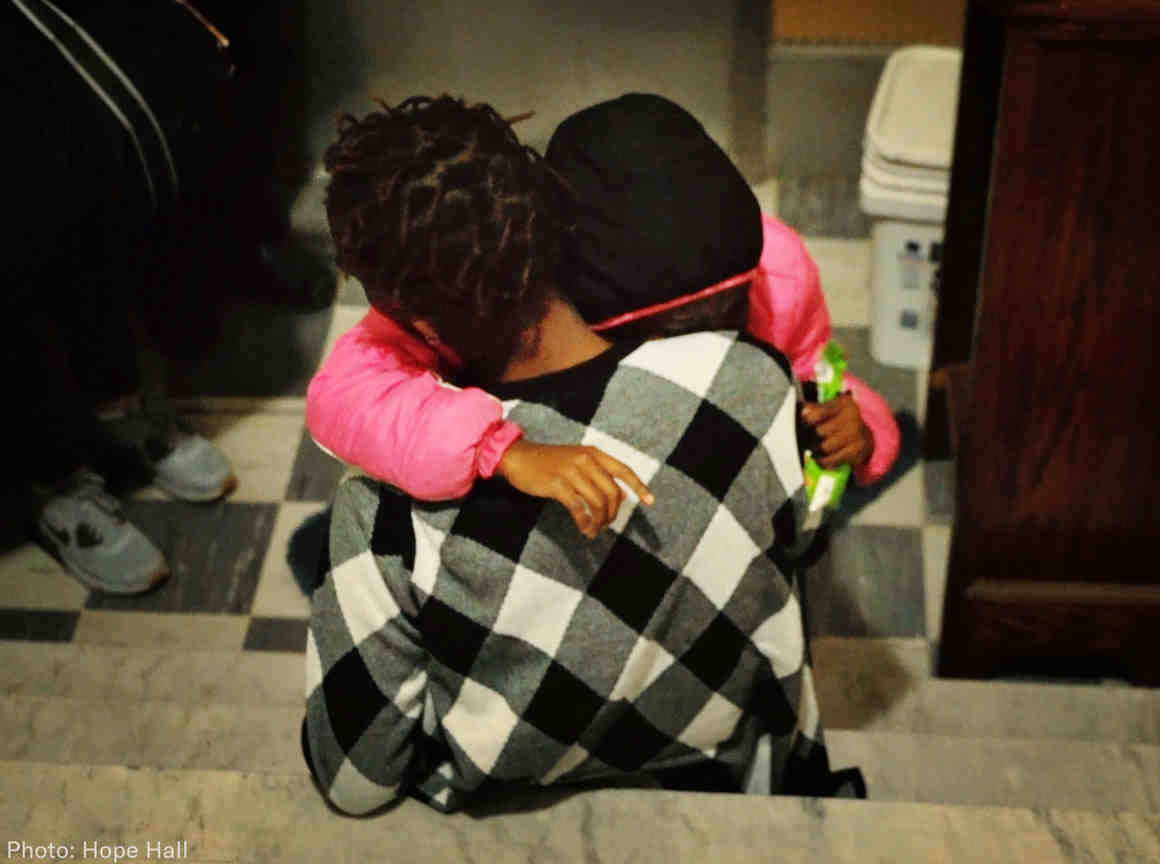

The practice was widely condemned by human rights activists and community leaders in the U.S. and abroad. “Detention of children is punitive, severely hampers their development, and in some cases may amount to torture,” United Nations human rights experts said in a 2018 statement. “We are deeply concerned at the long-term impact and trauma, including irreparable harm that these forcible separations will have on the children.”

In June 2018, a federal judge in San Diego ordered a stop to the practice and mandated that the government reunite the separated families.

Since then, under the judge’s orders, federal officials have been working to identify all of the separated parents and children. And the advocates who sued to halt the family separations have used that information to locate parents, many of whom were deported to Central America, and to make arrangements to reconnect them with their children.

The family separation story is now seldom in the headlines, but many children still have not been reunited with their parents, and new families continue to be separated at the border, albeit in smaller numbers. A recent inspector general’s report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the agency responsible for unaccompanied migrant children, suggests that it may be impossible to ever know the complete number of families who have been affected.

As the president enters his fourth year in office, KQED looks back at some key moments in the saga of this contentious government initiative and the many legal challenges to stop it.

April 11, 2017: The First Enforcement Memo

When Trump took office in 2017, the rate of illegal immigration into the U.S. was at one of its lowest points in the past three decades. However, the number of families with children arriving at the U.S. —Mexico border in search of asylum was rapidly increasing — particularly Central Americans fleeing violent conditions back home.

In an effort to halt the flow of those families, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions in April 2017 issued a memorandum asking federal prosecutors to prioritize the prosecution of certain immigration offenses, including “improper entry by an alien” to the United States.

A federal report later identified that memo, along with a separate enforcement initiative, as the directive that led the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to separate an increasing number of children from their parents along the El Paso, Texas, section of the border starting in July.

Some government officials have characterized what happened in El Paso as a kind of “pilot program” for the vast increase in family separations that would soon follow.

Feb. 26, 2018: The Family Separation Lawsuit

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against the federal government — Ms. L. v. ICE — on behalf of a Congolese mother who said she and her daughter had fled their home, “fearing certain death,” and were separated at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in San Diego. One month later, Ms. L.’s case became a class-action lawsuit representing all parents whose children were taken away from them at the border.

April 6, 2018: ‘Zero Tolerance’ Policy

Attorney General Sessions released another memo establishing the Trump administration’s so-called “zero tolerance” policy, with the goal of criminally prosecuting all adults entering the country without authorization.

“If you’re smuggling a child, then we’re going to prosecute you, and that child will be separated from you, probably,” Sessions said at a May 2018 law enforcement conference in Arizona. “If you don’t want your child to be separated, then don’t bring them across the border illegally.”

That hard-line policy gave immigration enforcement officials the green light to place thousands of undocumented parents in federal jails. And because minors aren’t allowed to be jailed with adults, their children were treated as “unaccompanied minors.” Children and infants were turned over to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, part of the HHS, which housed most of them in shelters or with foster families.

The outcry against the policy was swift. Lawmakers, religious leaders and medical professionals condemned it, while citizen activists took to the streets in protest. And at least 10 states, including California, threatened legal action.

In May 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement forcefully opposing the practice. “Separating children from their parents contradicts everything we stand for as pediatricians — protecting and promoting children’s health,” wrote Colleen Kraft, the academy’s president at the time. “In fact, highly stressful experiences, like family separation, can cause irreparable harm, disrupting a child’s brain architecture and affecting his or her short- and long-term health.”

June 20, 2018: Trump’s Executive Order

In response to the overwhelming backlash, President Trump signed an executive order on June 20, 2018, affirming that the government planned to continue prosecuting people for “improper entry,” but added that, “It is also the policy of this Administration to maintain family unity, including by detaining alien families together where appropriate and consistent with law and available resources. It is unfortunate that Congress’s failure to act and court orders have put the Administration in the position of separating alien families to effectively enforce the law.”

June 26, 2018: Judge Orders Stop to Separations

Less than a week later, U.S. District Court Judge Dana Sabraw, based in San Diego and presiding over the Ms. L. v. ICE case, ordered the government to stop the separations and swiftly reunify families.

“The facts set forth before the Court portray reactive governance — responses to address a chaotic circumstance of the Government’s own making,” Sabraw wrote in his decision.

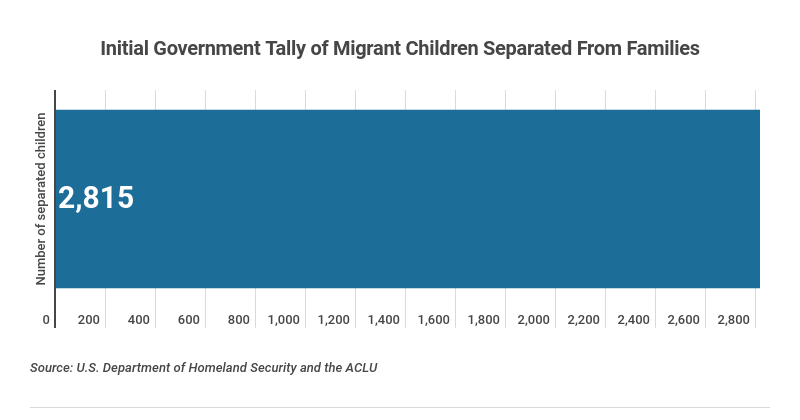

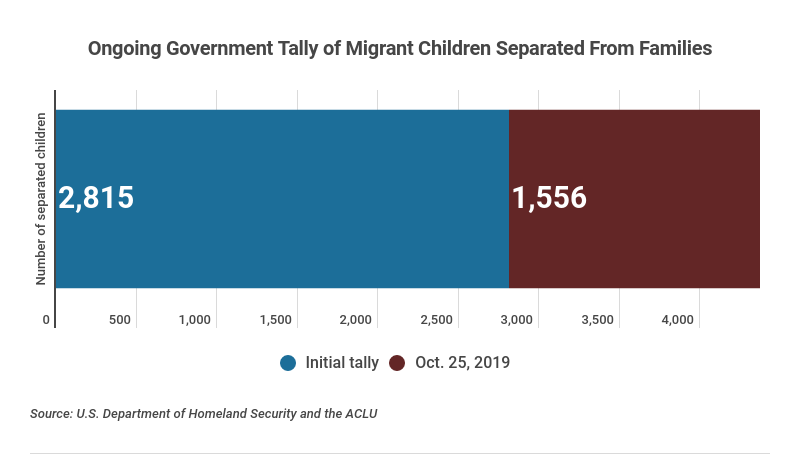

Under Sabraw’s supervision, federal officials began working to identify all the separated children in government custody at the time of the judge’s order. It took months, but eventually they tallied 2,815 children.

With the judge’s blessing, the ACLU formed a committee to track down the parents and find out how they wanted to proceed. Hundreds of parents had given up their asylum claims with the promise of having their children returned, only to be deported without them. Some of these parents decided their kids should stay in the U.S. with a relative to continue seeking asylum on their own. Others asked for their children to be returned to them in their home country. And a smaller number sought permission to return to the U.S. and resume their own petitions for protection.

March 8, 2019: Judge Orders Search for More Separated Families

In early 2019, the inspector general for HHS released a review of the agency’s internal data on separated children. The report found that staff members had identified many more children who had been taken from their parents but were no longer in the agency’s custody and so were not covered by “the accounting required by the court.” The report concluded that thousands of additional families had potentially been separated without an order to reunite them.

As a result, Sabraw in March 2019 expanded the class of parents covered by the Ms. L. lawsuit to include those who were separated between July 1, 2017 — when separations reportedly began in El Paso — and June 25, 2018, the day before his original injunction.

“Like the current class members, they too were separated from their children,” Sabraw wrote in the decision. “They were not reunited with their children despite the absence of any finding they were unfit parents or presented a danger to their children.”

This group of families was particularly difficult to identify because the children were no longer in the custody of the Refugee Resettlement Office, and Homeland Security officials had not told the agency that those children had been taken from their parents.

After months of investigating, government officials delivered their findings to the court on Oct. 25, 2019 — 1,556 additional children had been separated.

The ACLU’s steering committee set out to locate those parents and has since engaged community groups in Central America to assist. Some participants in the effort have described spending 12 hours walking around remote villages in search of a single parent. The effort is still being conducted.

July 30, 2019: ACLU Condemns Ongoing Separations

In Sabraw’s original injunction barring the separation of families at the border, he included an exemption for cases where authorities had deemed the parent unfit or a danger to the child.

Homeland Security officials have said they only rarely take such a step and only for the safety of children. But ACLU lawyers said the government had reported hundreds of ongoing separations after Sabraw halted the practice, including for minor criminal infractions, like petty theft or traffic violations.

In July, the ACLU asked the judge to clarify the standard for when the government is allowed to separate families in order “to ensure that children are not taken away from their parents absent an objective reason to believe that the parent is unfit or a danger to their child.”

According to the ACLU, government numbers show that, as of Dec. 21, 2019, 1,142 children had been separated due to this exception, bringing the total of all separated families to at least 5,513, with the government reporting a handful of additional separations each month.

“It is beyond shocking that the Trump administration continues to take babies from their parents,” ACLU lawyer Lee Gelernt said. “The administration cannot simply ignore the nationwide injunction over minor infractions.”

Jan. 13, 2020: Judge Approves Most Ongoing Family Separations

In January, Sabraw responded to the ACLU’s request for clarification as to when family separations at the border are acceptable.

In the ruling, he largely sided with the federal government, writing that child welfare standards are not the only consideration (as the ACLU had argued) — national security concerns are also a factor. “In this context, the government interests go well beyond just the fitness and danger that a parent may present to his or her own child,” Sabraw wrote. “Rather, the government interests extend to securing the Nation’s borders and enforcing the Nation’s criminal and immigration laws.”

He added that the government is entitled to separate children from their parents “based on any criminal history, not just criminal history that bears on a parent’s fitness or danger.”

Sabraw also asserted that the court should not “engage in prospective oversight” of family separation decisions, because the executive branch of government has the right to control security at the border. He also pointed out that separations at the border have declined dramatically.

Looking Ahead

In late 2019, HHS’ inspector general issued a new report about family separations that was made public in January. It stated that when the government began its zero tolerance policy of prosecuting all adult border crossers, including parents, Homeland Security officials lacked the technology to keep track of the thousands of parents and children they separated.

As of January 2020, hundreds — and possibly thousands — of families are still not reunited.

Out of the first group of 2,815 children identified, 18 separated children are still in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement — more than a year and a half after Sabraw ordered them returned to their parents.

And the the 1,556 additional families who the government determined had been separated under the zero tolerance policy as far back as July 2017, are still in the early stages. The ACLU’s steering committee has so far made contact with just 364 of those parents — by phone or by tracking them down in person on the ground in Central America. But advocates say those parents are so traumatized from losing their children that it’s hard to build enough trust to begin reuniting them.

“It can be a real struggle to ensure that the families believe that there can still be a path forward where reunification is even an option,” said Nan Schivone, legal director for the advocacy group Justice in Motion, and a member of the steering committee. “Our defenders are reporting that many deported parents are stuck in an emotional limbo, and it’s kind of hard for them to even process that they’ve been contacted and found.”

Then there are the 1,142 or more children taken from their parents after the judge halted family separations. So far, neither the government nor the ACLU has estimated how many of them have been returned to their parents.

In a recent legal filing, government officials expressed confidence that they’ve identified “substantially all the possible children” separated at the border. But during a December settlement conference, Sabraw voiced concern. “The unfortunate reality,” he said, “will be that we will never be able to accurately identify the number of children.”