The court authorized a committee of lawyers and advocates, overseen by plaintiffs’ attorneys, to track down current addresses and phone numbers for the parents in order to arrange to reunite them with their children.

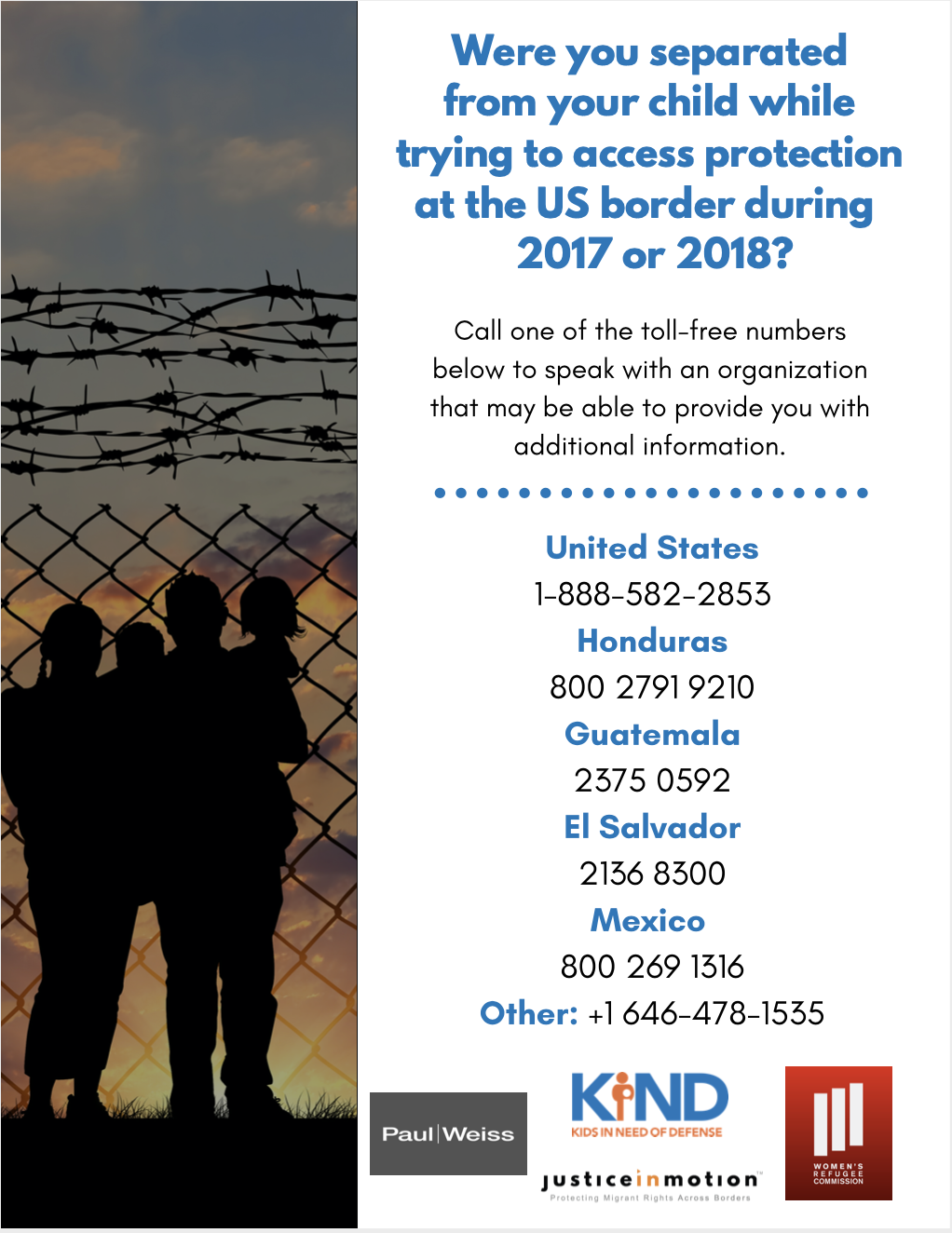

When all other efforts fail, it's up to a network of “defenders” — including local human rights lawyers and the staff of nonprofit organizations coordinated by Justice in Motion — to physically search on the ground in Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico.

The defenders, including Dora Melara, walk through towns seeking out families. They talk to neighbors and relatives, trying to track down a solid lead on where a person, or family, went.

“What we're talking about are hundreds of children (whose) families still haven't been found,” said ACLU attorney Lee Gelernt, who is lead counsel representing separated parents in the ongoing lawsuit against the Trump administration. “We don't know whether they are reunited. We don't know their situation. We're now in 2020 and this is still going on.”

The Pandemic

Before the coronavirus pandemic began, Justice in Motion's defenders were making slow but steady progress in the search. They’d been able to locate the parents of 135 children. In January, nine parents who had been deported were able to return to the U.S. to reunite with their children and pursue their asylum claims.

"That was such a hard-fought step toward justice, made possible only because of a massive and complicated cross-border effort," Schivone said.

But in March, when the pandemic hit, all on-the-ground operations in Central America stopped.

“We had to completely stop because of the pandemic,” Melara said. “The government started the rules, and we can no longer go out. There was a strict curfew.”

While defenders were able to connect with some people online, Melara said it’s much harder to build trust with traumatized parents digitally than it is in person.