Episode Transcript

Katrina Schwartz: Try to imagine the first time you saw the lights of an amusement park twinkling in the night sky…

To me those lights meant fun with my family, fried food and rides! Although to be honest, I’ve always had a little bit of a weak stomach for them.

Throughout the last 100 years or so, amusement parks like Marine World, Neptune’s Beach, Great America, and Discovery Kingdom have dotted the landscape here in the Bay Area … a few are still around, but most have closed for good. In a few years, California’s Great America in Santa Clara will become the next to close its gates.

This week we remember two amusement parks that have etched themselves into the imaginations of generations of Bay Area residents….Idora Park in Oakland, and San Francisco’s Playland at the Beach. This episode first aired in 2022, but we’re bringing it back to celebrate the end of summer. I’m Katrina Schwartz. You’re listening to Bay Curious.

Sponsor message

Katrina Schwartz: This week on Bay Curious, we look back at Bay Area amusement parks of yesteryear. Here’s reporter Christopher Beale.

Christopher Beale: In the early 1900s, Oakland was bustling with activity. The Model-T was still a few years away so cars weren’t super commonplace yet. The streets buzzed with bicycle and trolley traffic. The main streetcar around Oakland in those days was the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose Railway (SFOSJR), which later became the Key System. The streetcar and the land it ran on was owned by the very mob-sounding “Realty Syndicate.”

TJ Fisher: An impossibly evil name for a corporation.

Christopher Beale: This is TJ Fisher.

TJ Fisher: But the Realty syndicate was exactly what it sounded like.

Christopher: TJ grew up on the east coast. He now lives in the Castro in San Francisco and says he has loved and studied amusement parks, pretty much his entire life.

TJ Fisher: When I was in college, I wrote my thesis about different intersectional aspects of the way people enjoyed amusement parks over time and how that reflected other elements of culture.

Christopher Beale: The way TJ tells it, this group of wealthy businessmen…

TJ Fisher: The Realty Syndicate.

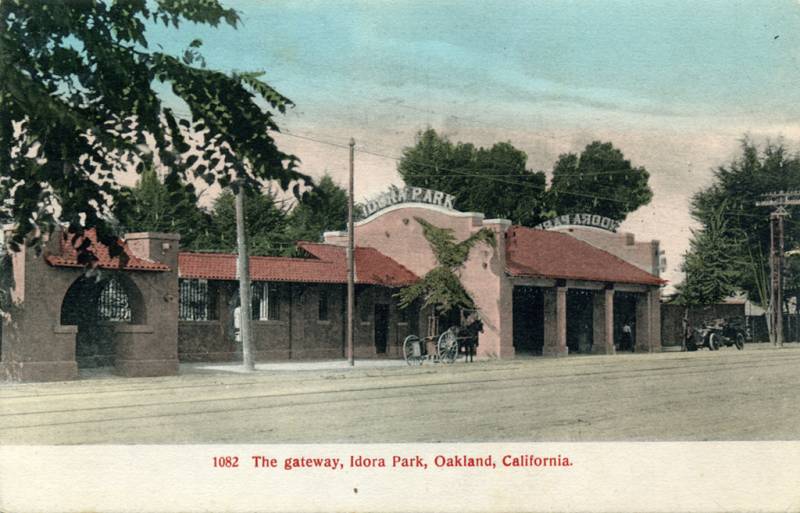

Christopher Beale: Owned the trolley system, as well as a lot of land around Oakland. The trolleys were busy on the weekdays with commuters, but on the weekends…not so much. This presented a cash flow issue for the Syndicate…they thought if they could boost weekend ridership there might be other benefits down the line. The Syndicate owned a piece of land in what is now North Oakland, just north of where the 24 freeway crosses telegraph now…

TJ Fisher: Between 56th and 58th streets and Shaddock and Telegraph.

Christopher Beale: And they leased it to this company called Ingersoll Amusements. Ingersoll set out to create a beautiful destination for Oaklanders, and the Realty Syndicate put a streetcar stop nearby. In 1904, Idora Park was born, and was an instant hit with locals.

TJ Fisher: It was just about 10 cents admission fee to get in, which would be about $3 in today’s money. That’s a fantastic bargain when you think about what it costs to get into Great America or Disneyland today.

Christopher Beale: That admission got you into the more than 17 acre park where there were roller coasters, slides, swings, and all manner of concessions.

TJ Fisher: You got the beautifully landscaped grounds. You got some, but not all of the rides, there were a huge number of things on display that would really get people thinking about new technologies. They had an experience that showed you what a coal mine was like. So those kinds of things would be included and then concessions like a roller coaster, a carousel would cost extra.

Christopher Beale: There was also an opera house, animals, exhibits, and a pool.

TJ Fisher: It was really a center of culture in Oakland before we had as many public city parks as we do today, you would go to Idora to get outside. It was really something that everybody would’ve known.

Christopher Beale: But the Realty Syndicate…that’s the trolley company…had another motivation for making this part of Oakland a destination.

TJ Fisher: They had always hoped that the area around the park would grow and be considered desirable and they would be able to use the park for another purpose. So it was a huge shock when at the end of 1928, it was announced that the Realty trust was going to subdivide the park and sell it as real estate. And so, things were dismantled very quickly in, uh, early 1929. and now it’s a very residential neighborhood and there are no signs that there was ever an amusement park there.

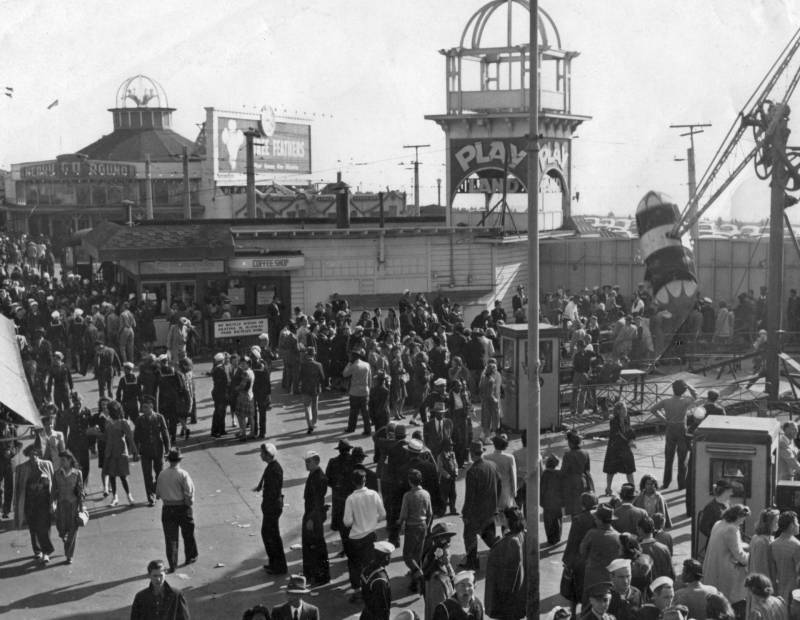

Christopher Beale: When Idora Park was at its most popular in the early nineteen hundreds, another amusement park popped up just across the Bay at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach.

Like Idora Park, new trolley lines played a big role…food stands and small rides greeted passengers riding all the way to the Western end of the line. Soon, the ragtag park would become a beloved getaway for young and old alike.

Jim Smith: In 1914 they actually put in the, uh, merry-go-round there. And that was the Loof’s Hippodrome.

Christopher Beale:That’s Jim Smith.

Jim Smith: I’m the author of, San Francisco’s Playland at the beach the early years and a second book, the golden years.

Christopher Beale: Loof’s Hippodrome was this ornate carousel, shortly after it opened it this guy John Friedel bought in and brought big ideas to the area residents were calling Chutes-At-The-Beach.

Jim Smith: Friedel decided that he wanted to make a first rate park out of it. So in 1919, he went in and started building a lot of rides and people loved it. I mean, at that time there was nothing near like it anywhere else in the west coast.

Christopher Beale: George Whitney became the manager in 1926 and formally changed the name of the roughly three block area to Playland-at-the-Beach.

Jim Smith: Now, one of the smart things they did was they, uh, made it free to get in the park. There were no gates. You just go down there and If you got a quarter or you got a dime, you could put those towards a ride.

Sound of LAFFING SAL

Christopher Beale: That’s Laffing Sal, possibly the most iconic character to survive Playland at the Beach. More on that later. She was a sort of early animatronic…and this was way before Disneyland. She was located at the entrance to the Funhouse. Jeanne Lawton remembers visiting in the 60s.

Jeanne Lawton: And always the scariest thing about going into the funhouse when wearing a skirt was the airholes in the floor that randomly would blow a shot of air as you stepped over them. We girls would scream with delight and try to jump over them before they got us, but we never succeeded.

Christopher Beale: One night she and her girlfriends discovered the secret to that gag.

Jeanne Lawton: I distinctly remember the day that I happened to look up in the balcony and saw a guy that was working there grinning from ear to ear, and then he would hit the button.

Christopher Beale: The Playhouse was one of a whole selection of attractions available at the park. There were food vendors too, one of the more popular ones was actually invented by George Whitney in 1928. When he got the formula right he is said to have yelled “It’s…it!” the It’s-It was born.

Jeanne Lawton: Back then they made their own oatmeal cookies, and then put a scoop of vanilla ice cream in between the cookies, and then dipped it in hot chocolate and handed it to you to eat right away.

Christopher Beale: You can still buy It’s-Its at many west coast grocery stores in the freezer section. A Lot of the attractions and food stands at Playland at the Beach were independently owned and operated. Like small businesses.

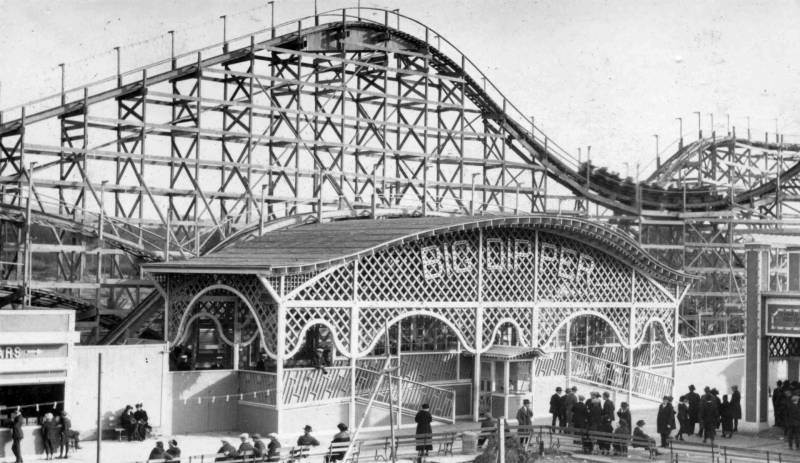

Jim Smith: Bob’s roller coaster. The merry-go-round. The Whirlpool ride, which you’re sitting in a cage spinning around, was really fast. They had, uh, Dodger, it was originally, it was called Dodge him, and then it became Dodger and they didn’t ever call ’em bumper cars cuz they didn’t want you to slam ’em into each other. They had to repair ’em. The big dipper when they built that was really tall.

Christopher Beale: 65 feet…like a 7 story building.

Jim Smith: And it had huge drops and long climbs. It was really an exciting ride and everybody wanted to ride that thing. By the way it had no seat belts, no bar, nothing to hang onto except the rail on each side. People did get hurt on that once in a while

Christopher Beale: Like the rides weren’t very safe were they?

Jim Smith: No, there was no OSHA back then!

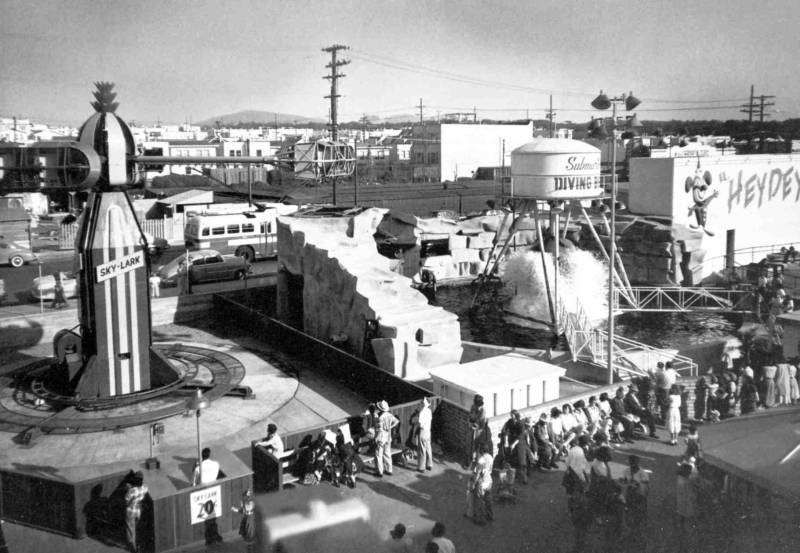

Sound of the Diving Bell

Jim Smith: Diving bell was fun. It was a bell shaped thing. Once you get in, they bolt down the door, you know, tie it down, like in a, like in a submarine They had this 40 foot deep, well, and as you were going down, you’d see fish in there. I mean, it had sharks. It had, uh, Octupie. It had all kinds of different, uh, salt water animals. I think it was designed this way on purpose it leaked, and the guy was operating. It would say uh oh, uh, oh, we’re leaking here. We’re gonna sink. I’m not gonna be able to get this thing back up. He says, let’s see . If we can come up. Well, he’d pull the brakes off this thing. And it would Bob to the top, like a cork. Some people thought it was a riot and some people were scared to death.

Christopher Beale: During the great depression in the 30s, Whitney was able to consolidate power by buying out other concessions as they failed, and through this he garnered control of much of Playland-at-the-Beach. The Whitneys even bought the land Playland sat on, and nearby plots for future expansion. But then, in 1958, George Whitney died. Without him, Playland-At-The-Beach was rudderless and began to fail.

Jim Smith: They started pulling down the rides. They tore down the Big Dipper.

Christopher: The property itself fell into disrepair, and folks stopped visiting. Then in 1972, Whitney’s widow sold Playland-At-The-Beach to a developer.

Jim Smith: They sold it to Jeremy Ets-Hokin.

Christopher Beale: Eventually the property’s new owner decided to close Playland.

Jim Smith: He wanted to build on it and he wanted to build these, uh, big condos up there. Everybody hated him in the city.

Christopher Beale in scene: Wait, why did people hate him?

Jim Smith: The way they saw it is he stole Playland from them. Nobody wanted to see a Playland go away except for the ones that wanted the money.

Christopher Beale: Ets-Hoken had the park torn down.

Jim Smith: He had no permission or anything. And then the city fathers got all ticked off. So they put a 10 year moratorium on building on that lot. So he was stuck with this thing. He paid a fortune for it, but he couldn’t do anything with it now.

Christopher Beale: The moratorium eventually ended. Today, those apartments that are various shades of pastels…and the Safeway on 48th Avenue, are where Playland-At-The-Beach… used to be. Thankfully, several important pieces of Playland survived the demolition. A pretty visible one is the big Wurlitzer organ at the Santa Cruz Boardwalk. Of course there is Laffing Sal, at Pier 45’s Musee Mechanique and the original carousel from Loof’s Hippodrome is still around too. Today the Leroy King Carousel, as it’s now known, is operated by the Children’s Creativity Museum at Yerba Buena Gardens.

Deyvi Solorzano: Key in the ignition. Bell time.

Bell rings. Overhead announcement: Welcome to the Leroy King Carousel! While the ride is in motion please remain seated facing forward.

Christopher Beale: Okay. So I heard that earlier and I thought it was a recording. I didn’t realize that was actually you saying that.

Deyvi Solorzano: That’s me. Yeah. My name is Deyvi Solorzano. I’m the operations and events coordinator here. carousel operator, amongst many other things.

Christopher Beale:Is it crazy to stand here every day and operate something that is like several lifetimes older than you like that has been around all this time and people have cared for it. And now it’s in your hands?

Deyvi Solorzano: Yeah. It’s a really cool job. Um, it’s not even a job. I don’t even, I I’m, I’m literally just here. This is not a job.

Christopher Beale: Yeah. Don’t, don’t tell them, you’ll do it for free though.

Deyvi Solorzano: Yeah, no, I won’t say that.

Christopher Beale: Idora Park closed 90 years ago…Playland has been gone almost 50 years. There are no pieces of Idora Park remaining, but these tangible memories of Playland-At-The-Beach, like organs, carousels, and weird carnival attractions like Laffing Sal will live on under the watchful eye of their caretakers. Allowing the next generation of thrill seekers, and those chasing nostalgia another trip back in time.

Katrina Schwartz: That was reporter Christopher Beale. Thanks to David Gallagher, Mike Winslow and Carol Tang for their help with this story.

We’ve got pictures galore of these old parks on our website … be sure to check them out at BayCurious.org. And while you are there, take a moment to vote in our August voting round.

Here are your choices:

Voice 1: How did Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley and Oakland become such a hub of East African cuisine?

Voice 2: What was South San Francisco “the birthplace of biotechnology,” and why is it still home to so much of the biotech industry today? Why didn’t it develop closer to universities in Palo Alto or Berkeley?

Voice 3: What’s the history of the concrete ruins in American Canyon right off Highway 29?

Katrina Schwartz: These three are neck and neck right now…but there’s still time to make your voice heard. Go to Bay Curious dot org to cast your vote.

Our team will be off next week for Labor Day, but we’ll be back with a brand new episode on September 11th.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is produced by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale and me, Katrina Schwartz.