Olivia Allen-Price: Hey everyone, this is Olivia Allen-Price and you’re listening to Bay Curious. The show that answers your questions about the San Francisco Bay Area.

Today we’re going to start the episode by venturing back in time, and into the night.

It’s the 1950s … and while most folks around the Bay Area have tucked themselves in by midnight, all cozy in their warms beds, things in San Francisco’s Fillmore District are just heating up.

[Distant jazz music wafts in, as if you’re hearing it from outside on the street]

Olivia Allen-Price: Jazz is on special here every night of the week.

Take a stroll down Fillmore Street and you might run into Billie Holiday stepping out of a restaurant … or Thelonious Monk smoking a cigarette.

The music of Dizzy Gillespie bleeds through the door of a music venue.

[Door opens, music gets much louder, like we’re in a club]

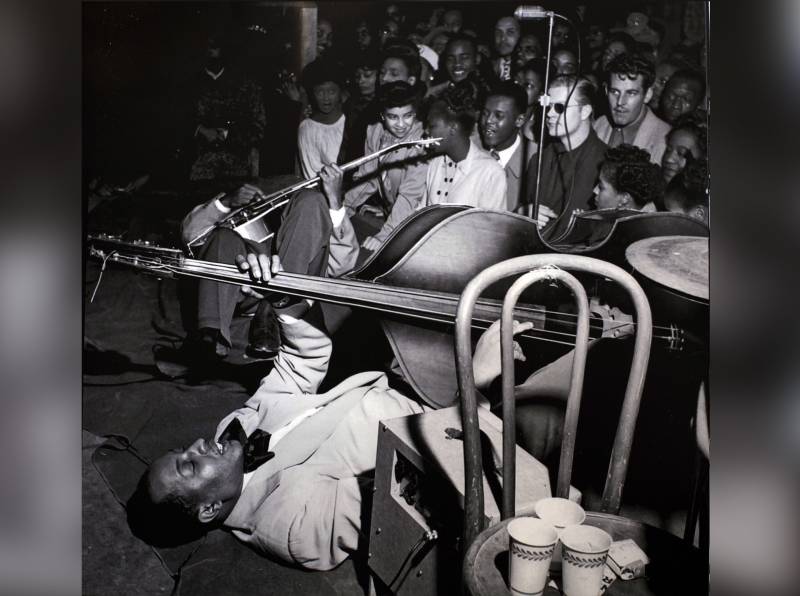

Step inside and you’re front and center for why this neighborhood got the moniker “Harlem of the West.” In the 1940s and ’50s, the Fillmore was THE spot on the West Coast to see the jazz greats.

Until … it wasn’t.

[Construction noises]

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on the show — how the Fillmore become a national hotspot for jazz, and how city planners dismantled it.

This story was inspired by a winning question from a public voting round on BayCurious.org. It first aired in 2020. But we’re bringing it back today because this story is featured in our newly released book, “Bay Curious: Exploring the Hidden True Stories of the San Francisco Bay Area,” which, I’ll just mention, is available at a local bookstore near you.

We’ll turn up the music, right after this…

Olivia Allen-Price: We’re delving into how a small neighborhood in San Francisco became an epicenter for jazz. Reporter Bianca Taylor brings us the story…

Bianca Taylor: Like so much of San Francisco history, the story of the Fillmore can be traced back to the day the city shook.

[Early 1900-music]

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: After the earthquake, pretty much all of San Francisco all relocated to the Fillmore simply because it was the closest place to downtown that survived relatively intact the earthquake and subsequent fire.

Bianca Taylor: Elizabeth Pepin Silva is a filmmaker and co-author of the book, Harlem of the West. She grew up in San Francisco. When she was a teenager, she got a job working for music promotor Bill Graham at the Fillmore Auditorium. It’s how she first started digging into the history of the neighborhood.

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: Once downtown was rebuilt, the local Fillmore Neighborhood’s merchants association were trying to figure out a way to keep people coming back to the neighborhood.

Bianca Taylor: It was decided that the Fillmore would be San Francisco’s entertainment center. In 1909, an amusement park called the Fillmore Chutes was built, complete with a wooden roller coaster and Ferris wheel, and three years later, the Fillmore Auditorium.

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: You know, there were beer halls. It was a really fun, exciting place. It was a place to go have fun. But it was mainly for white people.

Bianca Taylor: Yes, San Francisco was segregated, but in the Fillmore it was a little bit different. The earthquake had damaged a lot of neighborhoods where people of color were “allowed” to live in the city, but the surviving Fillmore district had inexpensive real estate and a history of accepting immigrants.

So through the early 1900s up until the 1940s, you had Filipinos, Mexicans, African Americans, Russians, Japanese Americans and Jewish people living next door to one another.

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: And it really became known as one of the most integrated neighborhoods west of the Mississippi.

Archival Newsreel: “On December 7th, 1941 Japan, like its infamous axis partners, struck first and declared war afterwards.”

Bianca Taylor: Then, Pearl Harbor was bombed. And the country changed completely.

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: Japanese Americans are forced into concentration camps and it left this huge hole in the Fillmore district.

Bianca Taylor: At the same time there was a push to recruit African Americans from the Midwest to work the shipyards in San Francisco and Richmond.

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: And they were given a free train ticket and promise of a job and they were like, “come on out we need you.”

Bianca Taylor: African Americans arriving in San Francisco moved into empty apartments the JapanesecAmericans had been forced out of. Between 1940 and 1950, the Black population of San Francisco grew tenfold. By 1945, some 30,000 African Americans were living in the city.

With this surge in population came an explosion in the Fillmore of Black-owned businesses, nightclubs, restaurants, and bars like…

Terry Hilliard: Circle Star

Mary Stallings: I hung out at Bop City

Terry Hilliard: Like Jack’s on Sutter

Mary Stallings: The Blue Mirror

Terry Hilliard: Booker T. Washington Hotel

Bianca Taylor: And you could go out on Friday night and not come home till Sunday night because there is so much to do. And so that’s how Fillmore became Harlem of the West.

[Music: “Soul Sauce,” Cal Tjader with Terry Hilliard]

Terry Hilliard: So, you know, when you play in the city, it just feels so wonderful that you have an audience of that caliber who enjoy your music.

Bianca Taylor: Terry Hilliard, who we’re hearing on this track by Cal Tjader, is a bass player who started playing in the Fillmore district when he was a student at SF State.

Terry Hilliard: We had great crowds. People really dressed up nice. The places were very elegant. There’s just a lot of joy.

Bianca Taylor: The Fillmore was one of the few places where, as a Black man, Terry could play a venue and enter through the front door.

Terry Hilliard: When we played the private party, we’d have to come in through the loading dock. We’d play the show and then we come back down through the kitchen. Didn’t feel that at the Fillmore. At the Fillmore, they were Black clubs.

[Music: “Sunday Kind of Love,” Mary Stallings]

Bianca Taylor: Jazz singer Mary Stallings, who we’re hearing here, was born in the Fillmore District in 1939.

Mary Stallings: My family came from the Midwest. I was the first born in San Francisco.

Bianca Taylor: She started singing gospel in her neighborhood church when she was 8 years old.

Mary Stallings: Growing up in that area, walking to church in the morning you cross that Fillmore area. It was just music … god, music everywhere. It was just an amazing experience and feeling, and I knew that I was living something very special.

[Music: “What a Difference a Day Makes,” Dinah Washington]

Bianca Taylor: When she was older, Mary worked at jazz clubs where she got to see her idols perform when they came through town, like Dinah Washington.

Mary Stallings: When I was a kid, I used to imitate Billy Eckstine. I used to imitate Dinah Washington. I used to imitate Billie Holiday. And it’s amazing. I worked with all these people and knew these people personally.

Bianca Taylor: But Mary and Terry both say it wasn’t just the music that made the Fillmore special.

Mary Stallings: You know, you felt like you were cared for. You know, you had a home life, but everybody else was your family, too.

Terry Hilliard: The reason it was so different was because of the culture. It had a culture that was a place where talent could be developed, whether it be music, art, dancing or whatever. It was there. It was a place where you could express yourself and be accepted by others and you had an audience. I just don’t see that today.

Bianca Taylor: Why don’t you see that today?

After World War II, President Truman signed the 1949 Housing Act, which authorized the demolition and reconstruction of urban neighborhoods that were considered slums. This policy of “redevelopment” specifically targeted neighborhoods that were low-income and not-white. So in the 1960s, with its old Victorian houses and mostly Black population, the Fillmore became the focus of San Francisco’s “urban renewal.”

Jazz clubs were shuttered. Businesses torn down. Geary Street turned into the massive four-lane Geary Boulevard, slicing through the heart of the neighborhood. Residents were forced out of their homes, often without much warning or adequate compensation. To city planners, this was urban renewal, but to the residents of the Fillmore, it felt like something else.

[Archival Tape] Man 1: And then this is part of redevelopment also.

James Baldwin: What do you mean? Redevelopment meaning what?

Man 1: Meaning removal of negroes.

James Baldwin: That’s what I thought you meant.

Bianca Taylor: That’s writer James Baldwin. In 1963, he came to San Francisco to interview Black residents for a documentary produced by KQED. In the film called Take This Hammer, Baldwin points out that even though San Francisco thinks of itself as a progressive city, its policies — like those of redevelopment — made it no different from Birmingham, Alabama.

[Archival Tape] James Baldwin: I imagine it’d be easy for any white person walking through San Francisco to imagine everything was at peace. Cuz it certainly looks that way on the surface. San Francisco’s much prettier than New York. And it’s easier to hide in San Francisco than in New York. You’ve got the view, you’ve got the hills. You’ve got the San Francisco legend too which is that it’s cosmopolitan and forward-looking. But it’s just another American city.

Bianca Taylor: The redevelopment of the Fillmore was one of the largest projects of urban renewal on the West Coast. It impacted nearly 20,000 people. And by the time new housing and storefronts were finally completed in the 1980s, most of the former Fillmore residents couldn’t afford to move back in.

According to the U.S. census, in the 1970s 10% of San Francisco’s population identified as Black. Today, that number is half.

Mary Stallings still lives in San Francisco but says going back to the Fillmore now breaks her heart.

Mary Stallings: I was trying to explain that in another interview and I didn’t get very far because I cried like a baby. Because I missed — I missed the community feeling, the feeling of family.

Bianca Taylor: Terry Hilliard lives in Oakland now. He kept playing music in the Bay Area, but says all the musicians he played with back then left and went to New York. They couldn’t afford to live here.

Terry Hilliard: The only ones, the musicians who stay here, were those who had jobs like me. I ended up being a computer programmer and others worked at other jobs. Then we just played as often as we could together.

Bianca Taylor: Jazz in the Fillmore isn’t entirely dead. You can catch a live jazz show six days a week at the Boom Boom Room on Fillmore and Geary. The free, two-day Fillmore Jazz Festival draws big performers each summer. But is it still the Harlem of the West? Elizabeth Pepin Silva says…

Elizabeth Pepin Silva: Oh, absolutely not. No way. No.

Sad jazz start.

Bianca Taylor: Cities change. It’s easy to romanticize the past… But listening to Mary talk about her childhood in the Fillmore, she keeps using this word:

Mary Stallings: It was just so magical as I look back, it was just magic. You know, I use that terminology when things just can’t explain it.

[Music: “Sunday Kind of Love,” Mary Stallings]

Olivia Allen-Price: Jazz singer Mary Stallings. That story was reported by Bianca Taylor.

A written version of this story is one of the 49 included in our newly released book: Bay Curious: Exploring the Hidden True Stories of the San Francisco Bay Area. Be sure to check it out to learn more fascinating things, like: How Mountain Bikes first got rolling in Marin or how a once-popular island became a ghost town in the middle of San Francisco Bay. You can find details at KQED.org/baycuriousbook.

We’ve also got a book event coming up on Thursday, Aug. 24 at Black Bird Bookstore in San Francisco’s Outer Sunset. Come by to hear me tell some stories! We’ll also play a little mini trivia game, have some audience Q&A, and I’ll be signing books. The event is free and starts at 7 p.m. This is our last event on the calendar for a while, so I hope to see you there!

Today’s episode was produced by Katrina Schwartz and Asal Ehsanipour. Audio engineering was by Rob Speight and Christopher Beale. The Bay Curious team also includes Amanda Font. Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana and Holly Kernan.