California state officials officials have declared a state of emergency across the state in response to the ongoing bird flu outbreak.

On Dec. 18, Gov. Gavin Newsom confirmed that 34 human bird flu cases have been detected in California and pointed to recent cases detected in dairy cows in Southern California as reason to expand monitoring of the virus.

Newsom’s announcement comes on the same day the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the country’s first case of severe illness in a person with bird flu living in Louisiana.

A human infection was previously detected in the Bay Area in November, in a child in Alameda County.

Since April 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has confirmed 61 bird flu infections among humans nationwide.

What does it mean that California declared a state of emergency over the bird flu outbreak?

According to the California Government Code, the governor can declare a state of emergency when the state, or part of it, is “affected by a natural or manmade disaster” and “emergency conditions require the combined forces of a mutual aid region or regions to combat.”

In this way, declaring a State of Emergency allows California to free up resources and change or suspend laws to focus on a public health issue, or damage caused by earthquakes or fires.

The state of emergency declared in March 2020 for COVID-19 lasted for almost three years. In that timespan, Newsom was able to dispense hundreds of orders of varying sizes related to the pandemic, ranging from stay-at-home measures to delaying the tax filing deadline.

For context, there are currently over 50 open State of Emergency proclamations in California — some statewide and some restricted to counties.

Health officials say that no person-to-person spread of bird flu has been detected in California, and that the risk of infection for the general public remains low. But almost five years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, these alarming headlines can be alarming to read.

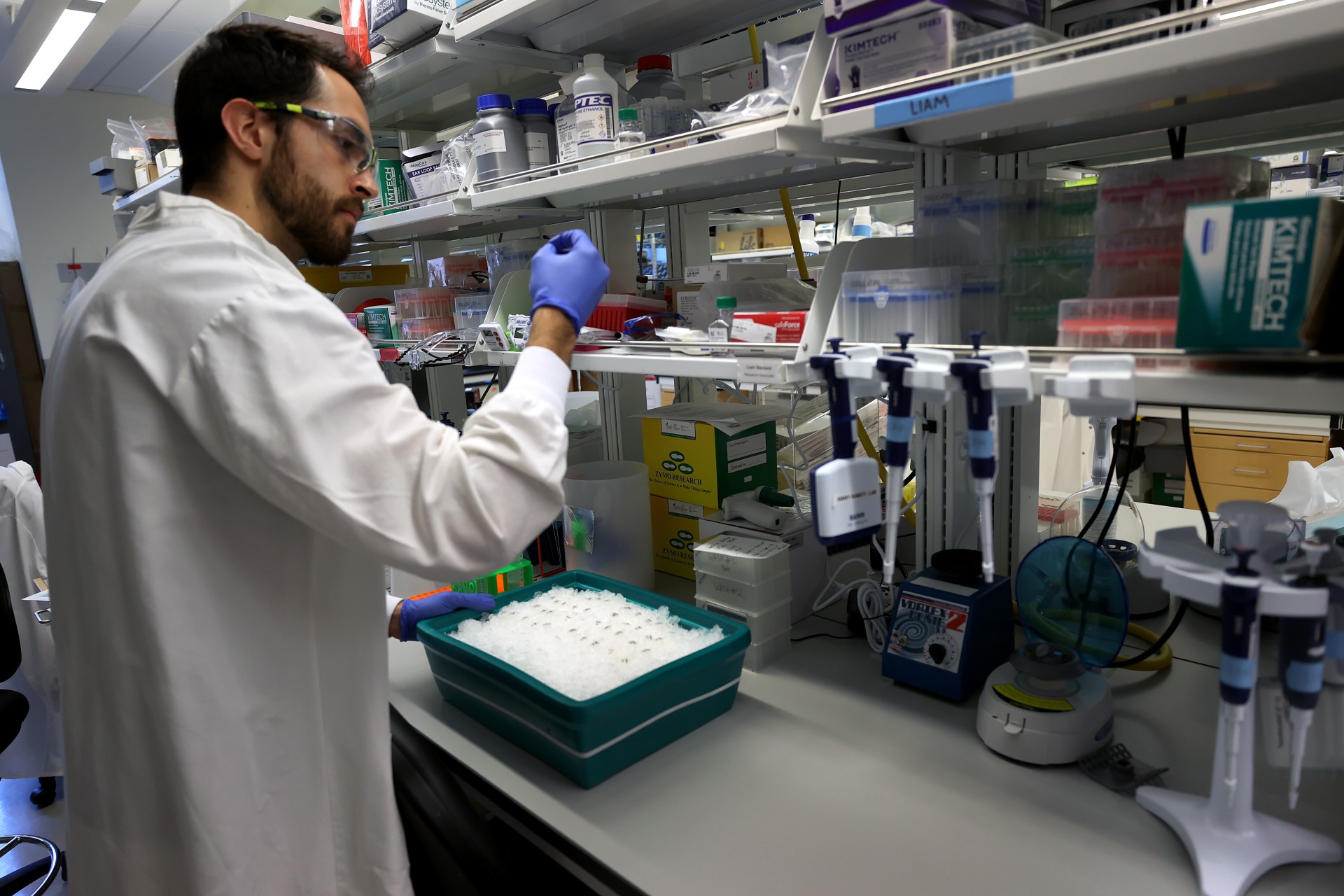

The public health experts KQED has spoken throughout the bird flu outbreak affirm that having accurate information about a virus is one way we can all better protect ourselves against future potential threats. “H5N1 is really a metaphor for lots of emerging threats in the future where we need to use the lessons we’ve learned during COVID and apply them again,” said Peter Chin-Hong, infectious disease physician at UC San Francisco. “We are being vigilant but not afraid.”

Keep reading for the latest on what researchers know about H5N1 — and how you can think realistically about the risks. Or jump straight to:

- What is bird flu?

- If H5N1 is spreading among cattle, how easily can it infect humans?

- How dangerous is H5N1 for humans? What are the symptoms?

- Is this another COVID-style pandemic?

- Is there anything I should be doing now to lower my risks?

What is bird flu?

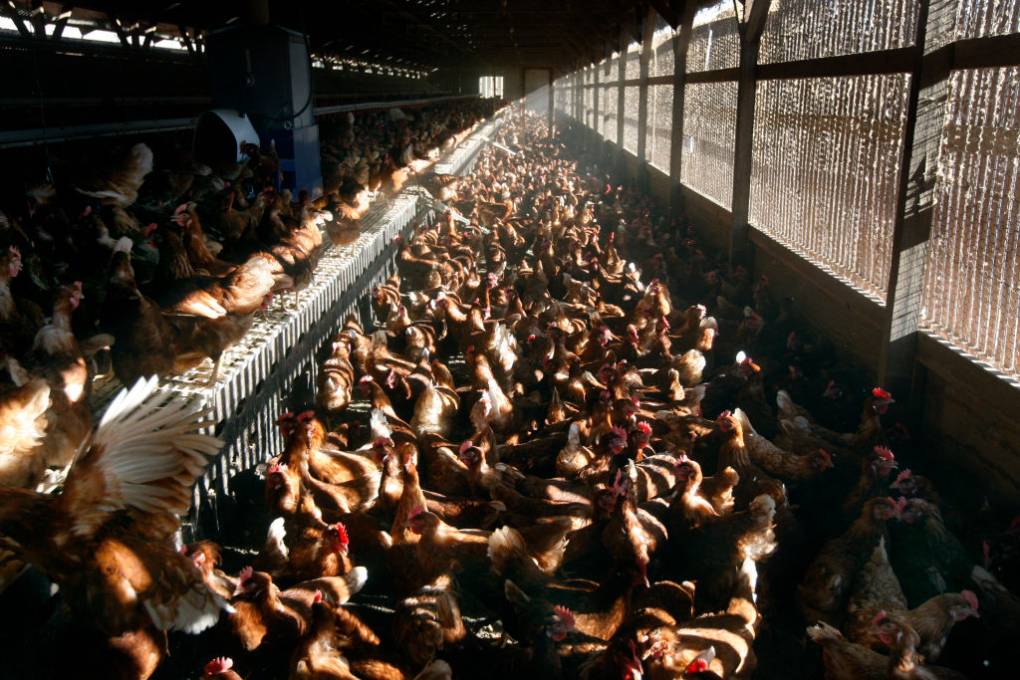

Bird flu, or avian flu, has existed among different bird species for centuries and is caused by the influenza A virus. Most of the time, the influenza A virus sticks to birds, but some strains can jump to other species. The seasonal flu we see each year, for example, is caused by the influenza A virus strain, while another strain of that same virus type caused the 2009 swine flu pandemic that cost tens of thousands of lives around the world.

Since 2023, a strain of the influenza A virus, H5N1, has mutated enough to infect a wide variety of mammals, including foxes in Finland, sea lions in Peru, and, most recently, dairy cows in the U.S.