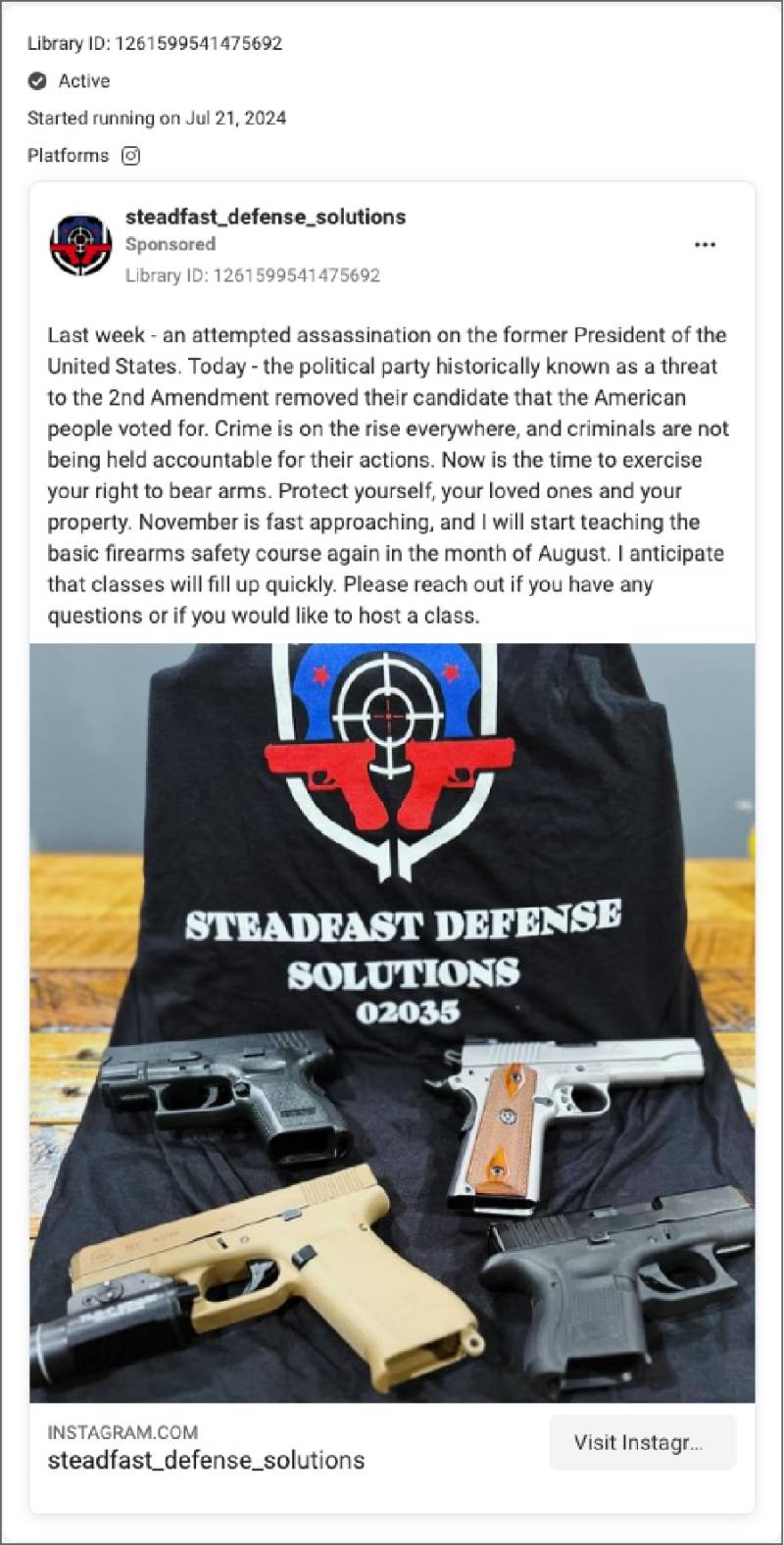

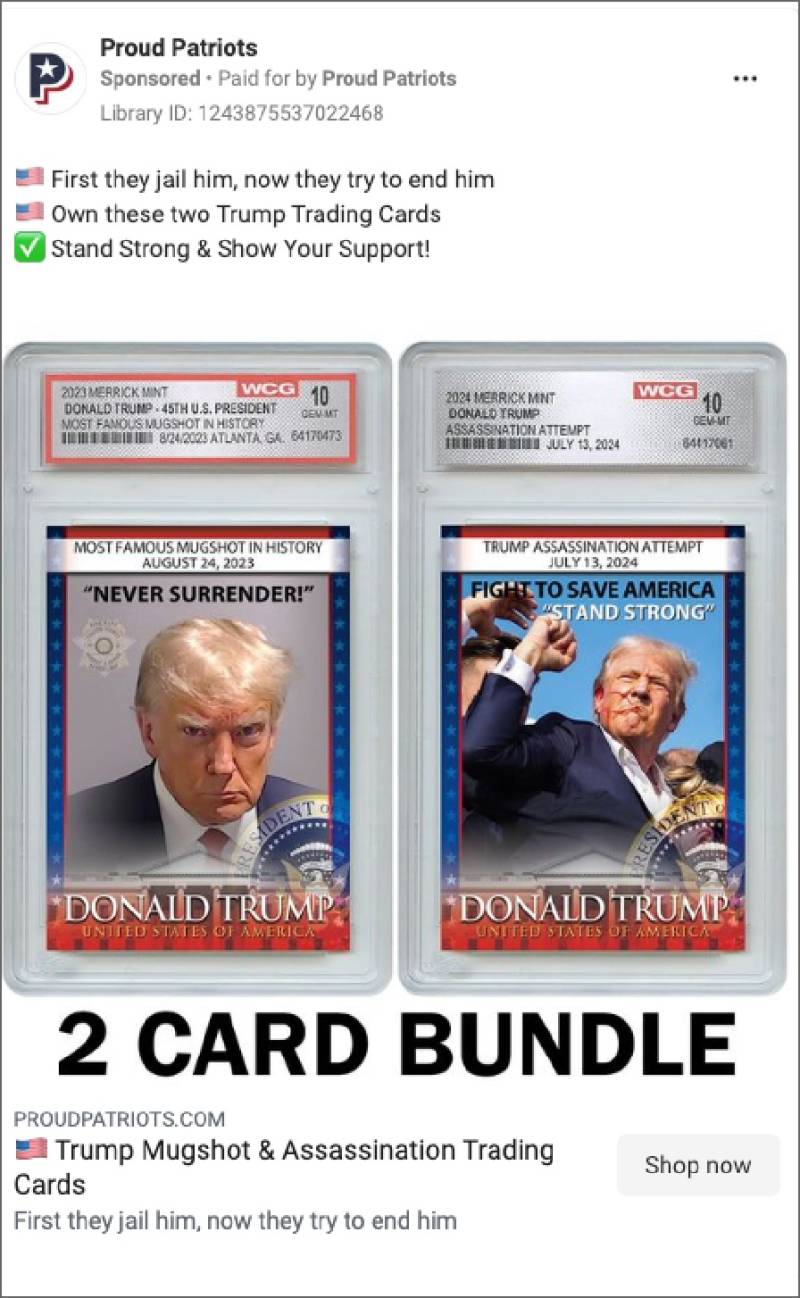

After the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in July, the merchandise started showing up on Facebook.

Trump, fist in the air, face bloodied from a bullet, appeared on everything. Coffee mugs. Hawaiian shirts. Trading cards. Commemorative coins. Heart ornaments. Ads for these products used images captured at the scene by Doug Mills for the New York Times and Evan Vucci for the Associated Press, showing Trump yelling “fight” after the shooting. The Trump campaign itself even offered some gear commemorating his survival.

As the Secret Service drew scrutiny and law enforcement searched for a motive, online advertisers saw a business opportunity in the moment, pumping out Facebook ads to supporters hungry for merch.

In the 10 weeks after the shooting, advertisers paid Meta between $593,000 and $813,000 for political ads that explicitly mentioned the assassination attempt, according to The Markup’s analysis. (Meta provides only estimates of spending and reach for ads in its database.)

Even Facebook itself has acknowledged that polarizing content and misinformation on its platform has incited real-life violence. An analysis by CalMatters and The Markup found that the reverse is also true: real-world violence can sometimes open new revenue opportunities for Meta.

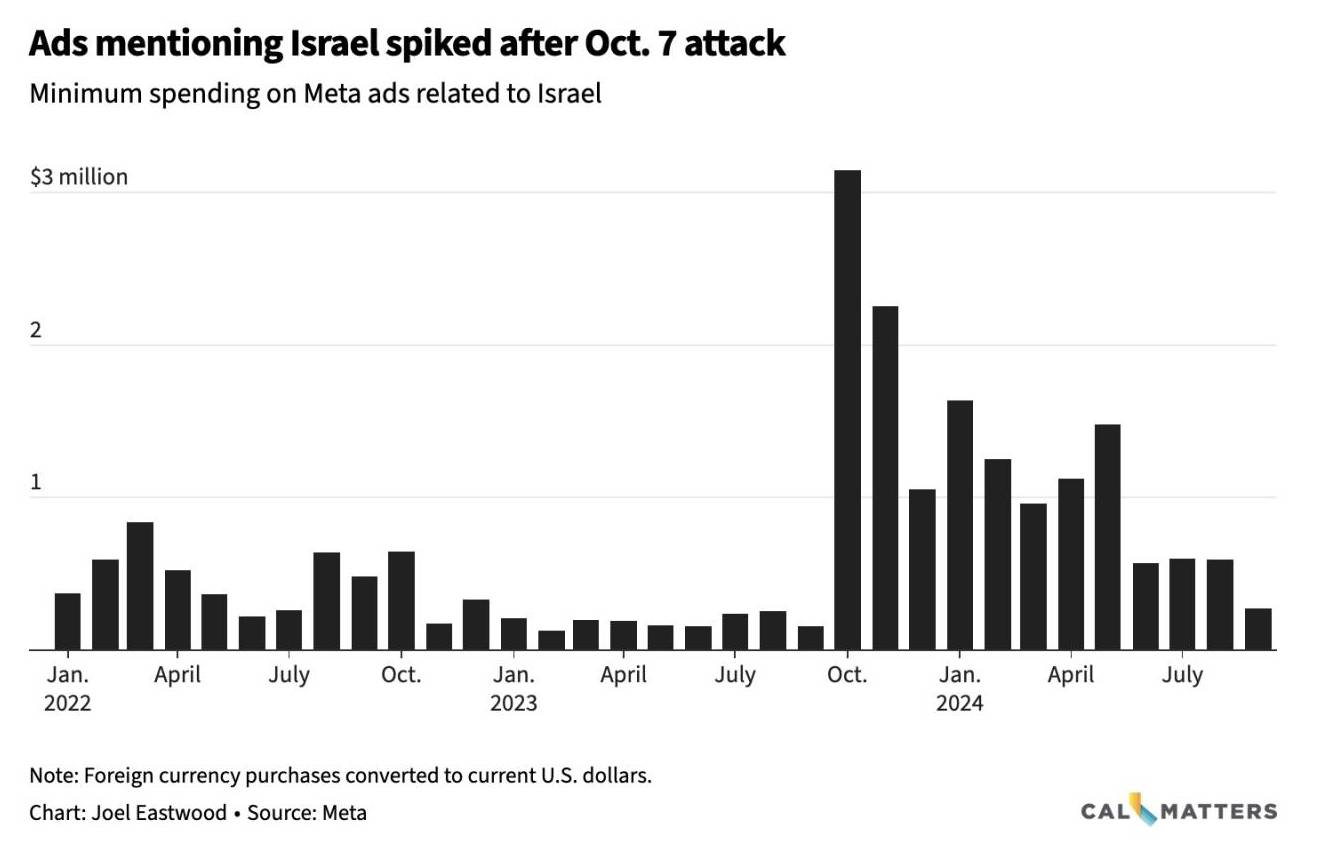

While the spending on assassination ads represents a sliver of Meta’s $100 billion-plus ad revenue, the company also builds its bottom line when tragedies like war and mass shootings occur, in the United States and beyond. After the October 7th attack on Israel last year and the country’s response in Gaza, Meta saw a major increase in dollars spent related to the conflict, according to our review.

Tech advocacy groups and others question whether Facebook should even profit from violence and whether its ability to do so violates the company’s own principles of not calling for violence. The company said advertisers often respond to current events and that ads that run on its platform are reviewed and must meet the company’s standards.

If you count all of the political ads mentioning Israel since the attack through the last week of September, organizations and individuals paid Meta between $14.8 million and $22.1 million for ads seen between 1.5 billion and 1.7 billion times on Meta’s platforms. Meta made much less for ads mentioning Israel during the same period the year before: between $2.4 million and $4 million for ads that were seen between 373 million and 445 million times. At the high end of Meta’s estimates, this was a 450% increase in Israel-related ad dollars for the company. (In our analysis, we converted foreign currency purchases to current U.S. dollars.)

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee, a lobbying group that promotes Israel, was the major spender on ads mentioning Israel. In the six months after October 7th, its spending increased more than 300% over the previous six months, to between $1.8 million and $2.7 million, as the organization peppered Facebook and Instagram with ads defending Israel’s actions in Gaza and pressuring politicians to support the country.

As the war has roiled the region, AIPAC paid Meta about as much for ads in the 15 weeks following October 7th as the entire year before.

“Our effort is directed to encouraging pro-Israel Americans to stand with our democratic ally as it battles Iranian proxies in the aftermath of the barbaric Hamas attack of October 7th,” Marshall Wittmann, a spokesperson for AIPAC, said in an emailed statement.

(See the data on our Github repo).

Other ad campaigns mentioning Israel supported different sides of the conflict. Doctors Without Borders, for example, used advertising to highlight the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Other ads defended and promoted Israel. The Christian Broadcasting Network tied the October 7th attack to a claim in an ad that Iran’s “final, deadly goal” was “to establish a modern caliphate—an Islamic-founded, tyrannical government—across the world.”

Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, takes in the vast majority of its revenue from targeted advertising. The company tracks users online to profile their habits and, when a business or organization wants to reach them, lets those businesses pay to send ads to people who might be interested. Those ads might be tied to something perfectly wholesome, like gardening. But the company’s algorithms don’t distinguish between simple hobbies and something darker.

Meta spokesperson Tracy Clayton said in an emailed statement that Meta did not ultimately profit from political violence, as advertisers broadly back away from advertising during times of strife for fear their ads will be promoted alongside news of the violence.

Clayton noted Meta’s chief financial officer recently said on an earnings call that it is “hard for us to attribute demand softness directly to any specific geopolitical event” but had seen lower ad spending “correlating with the start of the conflict” in the Middle East, and had seen similar at the start of the war in Ukraine.

“Advertisers responding to current events are nothing new, and it’s seen across the media landscape, including on television, radio, and online news outlets,” Clayton said. “All ads that run on our platform must go through a review process and adhere to our advertising and community standards, and Meta offers an extra layer of transparency by making them publicly available in our Ad Library.”