Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: Tom Rauch grew up in Berkeley in the 1960s.

He has vivid memories of that time. His mom worked at UC Berkeley and his dad was a grad student there, so he and his brother spent many days riding their bikes around campus.

Another memory he still thinks about to this day… one of his most vivid… is going to the Berkeley dump.

Tom Rauch: It really was just this big, giant pit where you backed up your car. You know, you turned around, you backed up your car, opened up your trunk and just shoveled whatever you had into this open pit.

Olivia Allen-Price: It was on the west side of Berkeley, right on the water. It was like the Wild West. It smelled rank. It was loud, with big bull dozers shifting and compacting the garbage. And then there were the birds! Hundreds of sea gulls squawking above the roar of the machinery…

Tom says back then, it seemed like the dump stretched for miles.

Tom Rauch: And as a little kid, of course, I was fascinated by this because there was all manner of things. You know, there’s refrigerators and lumber and whatever people didn’t want. It was just sitting right there and the bulldozers would come and, of course, you know, push it over.

Olivia Allen-Price: Now… fast forward to today… and the dump is long gone. In its place is Cesar Chavez park… a big grassy expanse with sweeping views of the entire bay. And Tom still visits! He goes once a month or so with his family… to walk around and take in the views. But he recently started to wonder about the old dump. Was it really the way he remembers it? How could it go from a squalid mass of junk… to this beautiful shoreline park, where people go to walk their dogs, fly kites and have picnics? So, he did some research. Or, he tried.

Tom Rauch: There is a surprisingly almost nonexistent amount of information about it there. Really. I couldn’t, maybe there are, but I couldn’t find any images of it. I couldn’t find any kind of recollections of it, any historical documents associated with it.

Olivia Allen-Price: So, he did what any Bay Area resident does when they have questions they can’t find the answers to: He reached out to Bay Curious.

Theme music

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price and on today’s episode of Bay Curious… how did Berkeley’s former landfill site become one of its most popular public parks? And what are some of the challenges of turning a big pile of trash into a recreational space? All that, after this break.

Sponsor message

Olivia Allen-Price: To uncover the mystery of the Berkeley dump we asked reporter Dana Cronin to see what she could dig up.

Dana Cronin: As a frequent visitor to Cesar Chavez park… I was excited about this one. I love taking my dog there to run the perimeter of the park. On a clear day, I don’t think there’s a better view of the Golden Gate Bridge. But… I was not around in the 1960s, and had no idea about the park’s former life as a landfill.

So, I called someone who does.

John Roberts: It was pretty thrilling to come down and just dump stuff out. And I don’t. You didn’t do it. I guess you were it before your time.

Dana (laughing): Yes.

Dana Cronin: This is John Roberts. He’s a landscape architect here in Berkeley. I meet him … surprise surprise… at Cesar Chavez park.

Park sounds

Dana Cronin: It’s a slightly cool and breezy morning, and we’re sitting on a park bench overlooking the bay. Ground squirrels dart around us, birds fly overhead, and a sea lion pops its head out of the water. It’s beautiful out here. But, as John likes to remind me…

John Roberts: This is garbage. We’re on our garbage.

Dana Cronin: And let me just say, talking with John has totally changed how I think about this park. Before I met him, I thought of it as a beautiful green park with great views. But John still sees it as a big pile of trash, covered in grass. He says it could have been so much more.

Music

Dana Cronin: The Berkeley dump stopped receiving waste in the mid-80’s, and the city decided to landscape it and turn it into a park.

To do that, they had to seal off the garbage… to prevent leakage and contamination. So, they trucked in a whole lot of soil.

John Roberts: There’s a four foot cross section of garbage. Then there’s two feet of clean soil and two feet of compacted clay and a foot of a foot of topsoil on top of that.

Dana Cronin: This layer cake of garbage and soil was capped with grass. And that’s pretty much how it looks to this day. Those rolling, green grassy hills? It’s all just grass-covered garbage.

But this wasn’t always the plan. After it capped the pile of trash, the city started to think about how to develop the space. Should it have tennis courts, a redwood tree grove, a playground?

The city put out a call to landscape architects for design proposals.

That’s where John comes in.

John Roberts: 1986 or ’87, something like that, there was a call for proposals and I was selected as the prime consultant.

Dana Cronin: He had all kinds of ideas. He was working with another consultant based in Seattle, who had worked on landfills before. And he had the idea to treat this site like a big compost pile.

In other words, instead of capping and forgetting about the garbage… they would dig it up, clean it up, and encourage it to break down naturally… with the help of the already-existing bacteria and microbes.

John Roberts: The garbage is being cleaned up by the bugs that are here. And we could use that to our advantage.

Dana Cronin: Ultimately, John wanted to return this spit of land to its original form — before all the garbage. Or at least, as close as he could get.

The area used to be all marsh so John wanted to cultivate native plant species… dedicate space to wetland habitat… maybe even build a beach where humans and animals could access the bay more easily.

But… as you may have guessed by now… none of that stuff happened.

After spending about seven years on this project, the city of Berkeley decided NOT to move forward with John’s proposal.

John Roberts: They found a 57-word phrase that said how much they liked the plan and how it reflected all their values, but they couldn’t approve it.

Dana Cronin: The proposal was bold and broke a lot of norms for landfill restoration. John says he thinks it was just too complicated and too much of a hassle for the city. He says money was probably a factor too.

Dana Cronin (to John in tape): How did it feel at that final vote when they endorsed but, you know, chose not to move forward with the project. How did you feel after having worked on it for so long?

John Roberts: Disappointed. I didn’t come out here for 15 years, I could see what it could have been. It could have been something so much different.

Music

Dana Cronin: Had the city moved forward with John’s proposal, the park would look much different than it does today.

It also potentially could have saved the city of Berkeley from a lot of maintenance issues that have cropped up over the last several years.

Because, as it turns out, that decision to keep the garbage underground has led to some complications.

First of all as it breaks down the garbage is producing methane. Methane is a combustible gas, so they can’t just leave it there.

Instead, they’ve put in a series of pipes underground to collect it. If you visit and look for them, you can see white access pipes sticking out of the ground every 200 feet or so throughout the park.

John Roberts: So here we are. There’s a white pipe there. You see another white pipe over there, the white pipe sticking up all over the place.

Dana Cronin: All that methane is sent to a flaring station on the east side of the park, near the dog area, where it burns off.

Flaring station ambi

Dana Cronin: The flaring station is a bit of an eyesore. And it can also be dangerous. Air regulators have issued numerous notices of violation to the city of Berkeley over its management of the landfill flaring. Violations include missing gas collection wells, severe methane leaks, and failure to continuously operate the system during power outages.

Last year the air district fined the city 130-thousand dollars for air quality violations. I did reach out to Berkeley city officials for this story. They declined my request for an interview.

Music

Dana Cronin: Now, it’s not just air regulators that have been keeping a close eye on the park. Water regulators are too. Specifically this guy…

Keith Roberson: Hi, my name is Keith Roberson.

Dana Cronin: Keith works for the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board. He’s responsible for overseeing landfills — both active and closed — to ensure they’re not contaminating the bay. Two years ago, he started to worry about the old Berkeley dump.

Keith Roberson: In May of 2023, I was having a phone conversation with one of my colleagues at the DTSC.

Dana Cronin: DTSC is the Department of Toxic Substances Control. It’s a part of the EPA, and it’s in charge of landfills that house hazardous waste.

Keith Roberson: My counterpart at DTSC mentioned, you know, by the way, I have run across a document that I want to share with you that indicates that the Berkeley landfill and the Albany landfill as well apparently had accepted some material from a chemical plant in Richmond that was known as Stauffer Chemical.

Dana Cronin: Hazardous material, that is. This letter was from the 1980’s, from the Stauffer Chemical company… and indicated that waste from one of their pesticide manufacturing facilities had likely ended up at the Berkeley landfill.

Keith Roberson: That’s when we first learned that, you know, there was a possibility or a likelihood that the Berkeley and Albany landfills had accepted some radioactive material.

Dana Cronin: Stauffer processed aluminum ore in their pesticide production, and the type of ore they used contains some naturally occurring radioactive elements. And this changed everything. Prior to this letter, there hadn’t been any indication that the Berkeley landfill contained any hazardous material. This was a matter of public safety.

So, Keith sent letters to both cities, asking them to do some radiation testing at their respective parks.

And late last year, Berkeley did just that. With the help of UC Berkeley experts, the city attached a highly sensitive radiation sensor to a drone, and flew it over the park.

And then, the results were in.

Keith Roberson: They did not find any spectral variation in the gamma signal.

Dana Cronin: In other words…

Keith Roberson: There’s really no indication from the Gamma survey that there are any places on the surface of the Berkeley landfill that pose a threat to human health.

Dana Cronin: So, that’s obviously a relief. But, the city also took some water samples during this survey. And Keith says, those results were a bit more concerning.

Keith Roberson: They did find elevated concentrations of radium 226 in their water samples.

Dana Cronin: Radium 226 is a radioactive compound, which, with enough exposure, can cause cancer and even death in humans. But Keith says they didn’t detect concentrations that high at the park.

Keith Roberson: Now, whether or not that poses any threat to humans above the surface, we don’t think so. Does it pose a threat to water quality in the bay? We don’t think so. But we’re still in the process of analyzing that.

Dana Cronin: But, Keith says, clearly there’s something buried in that pile of trash that’s starting to leak out.

Music

Dana Cronin: Now, Cesar Chavez park isn’t the only former landfill site-turned beautiful park in the Bay Area. The Albany Bulb — for example — used to be a landfill for construction debris. And, as Keith mentioned earlier, the Bulb was also tested for radiation. Luckily, levels there were also not dangerous to human health.

The Petaluma dog park… Byxbee Park in Palo Alto… all former dumps!

Keith says yes, there are risks with turning a landfill into open space, but…

Keith Roberson: From the water board’s perspective, that’s probably our preferred usage.

Dana Cronin: What’s more risky, he says, is trying to convert a former landfill site into, say, a commercial space. But, given the high value of land here in the Bay Area, some cities are doing just that.

The city of Santa Clara, for example, recently decided to move forward with a proposal to put a shopping center, office space and even condominiums on a former landfill site, near Levi’s Stadium.

That’s a little more concerning, Keith says.

Keith Roberson: Landfills contain organic material that’s decomposing. So the landfill surface is subsiding and it doesn’t subside evenly. You know, some parts may drop four feet, some parts may drop 12ft. So you get this very uneven hummocky surface.

Dana Cronin: He says it takes a lot of planning to put a building on top of a former landfill and, even then, it’s risky — especially for the groundwater. Also, a lot of these former landfill sites lie right on the water line, which poses a real risk with climate change and sea level rise.

Music

Dana Cronin: Tom, our question-asker, went on a walk in Cesar Chavez park recently. He says he wanted to refresh his memory of the place.

It was a cold and rainy day. He says he was struck by how beautiful it looked… and at the outstanding views of the San Francisco Bay.

Tom Rauch: And at the same time, there was that little tug about, well, you know, I know we shouldn’t have this, but it would be so much fun if you could still drive your car to the mouth of this pit and just shovel away and have the seagulls and the bulldozers keeping you company.

Dana Cronin: Tom says he gets that these days a landfill right on the water isn’t a great idea. And even though the Berkeley dump is long gone… his vivid memories of the smells, the sounds, the whole experience of the place… remain.

Music

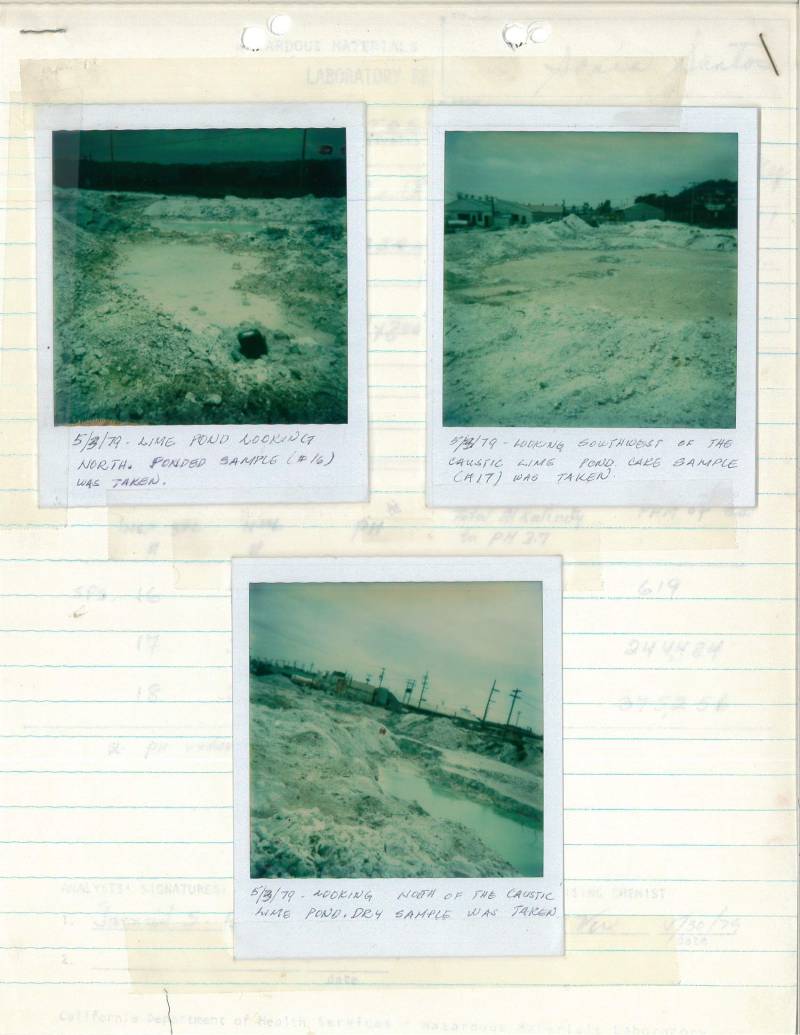

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Dana Cronin. Thanks to Tom Rauch for asking this week’s question. You can check out what the old Berkeley dump used to look like by heading over to Baycurious.org. We’ve got archival photos and new ones too! And while you’re there, why not sign up for the Bay Curious newsletter? We answer even more of your questions there and it only comes once a month, so it won’t clog your inbox.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Extra support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED Family.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Have a great week.