When the call came from the local health department in northeast Nebraska, Katie Berger was waiting. She had already gotten a text from the salon where she’d gotten her hair done recently, telling her that one of the stylists had COVID-19. She knew she was at risk.

“They said, ‘We’re calling to inform you that you were exposed to a COVID-19 patient,’ ” Berger says. “It was still pretty scary getting that call, even though I knew it was coming.” The public health official told her to monitor her temperature and watch for possible symptoms until two weeks after the haircut — April 17. Berger’s been staying at home since that call, hoping her quarantine will end uneventfully.

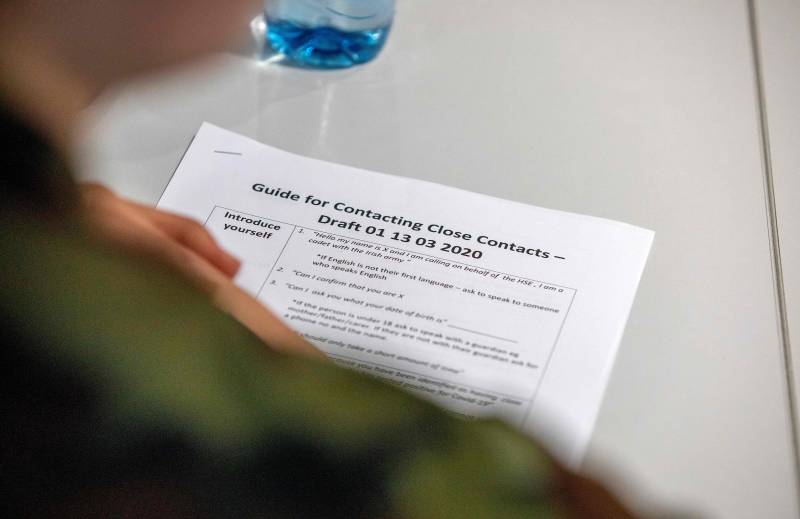

This process is called contact tracing. It’s been a critical tool to control the spread of infectious diseases for decades. Now, public health leaders are calling for communities around the country to ramp up capacity and get ready for a massive contact tracing effort to control the coronavirus.

Here’s a guide to the basics of the process and how it could help society restart after the current wave of coronavirus cases.

Identify and isolate: How to stop infection from spreading

Contact tracing is a process designed to halt the chain of transmission of an infectious pathogen — like the coronavirus — and slow community spread.

When someone tests positive for an infectious disease they become a “case.” Public health workers then reach out to the case, first of all to make sure they have what they need and that they are self-isolating, and then to figure out who they had contact with who may be at risk of infection, too.

“The whole point of this process is to make sure that people who have the virus are separated from those who don’t,” says Josh Michaud, associate director for global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “That includes the original case, who’s isolating, and the contacts who might be incubating the disease. If you get them to self-quarantine before they are infectious, then you’ve essentially stopped the transmission of that disease from that transmission train. If you do that with enough contacts, then you’ve effectively interrupted community transmission.”

It’s not perfect — a tracer might not be able to reach all the contacts, and those contacts might not all follow the guidance, says Dr. Jeff Engel, senior adviser for COVID-19 to the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. “But even the leaky quarantine is effective,” he says. “If you get 85% of contacts to self-quarantine for 14 days, you’re going to do a lot in the community to decrease transmission.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))